New DTM page: Holiday Cheer and Voice Leading.

Author Archives: Ethan Iverson

West Coast Piano

1950’s business cards from Anne Seidlitz (WOW!)

Last week I published “Deck the Halls with Vince Guaraldi” at the New Yorker Culture Desk. The essay has been generally well received, except by die-hards who can’t accept any critique of their God Guaraldi.

Truthfully, I’m actually a little abashed about celebrating Guaraldi, for in no way is he a jazzer’s jazzer. If you are talking West Coast piano of a certain era, many serious fans love Hampton Hawes and Jimmy Rowles more than Vince Guaraldi. But it is through Guaraldi’s fame that I can sneak in Hawes’s and Rowles’s names into that famous New Yorker font: “Though his (Guaraldi’s) bebop lines were enjoyable, he lacked the fire of Hampton Hawes or the mystery of Jimmy Rowles.”

To make up for going commercial with Charlie Brown, I thought I’d transcribe some things by the greater masters.

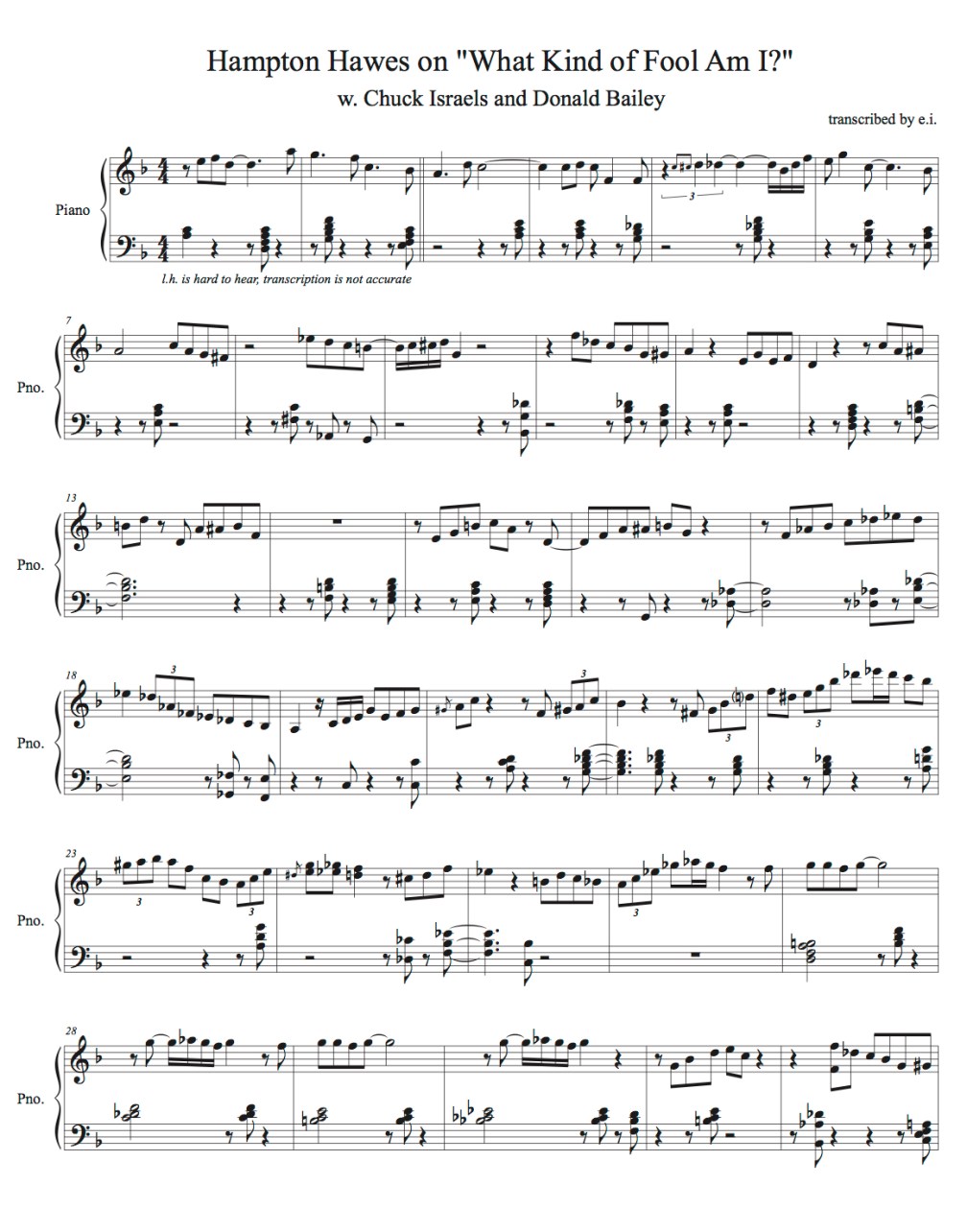

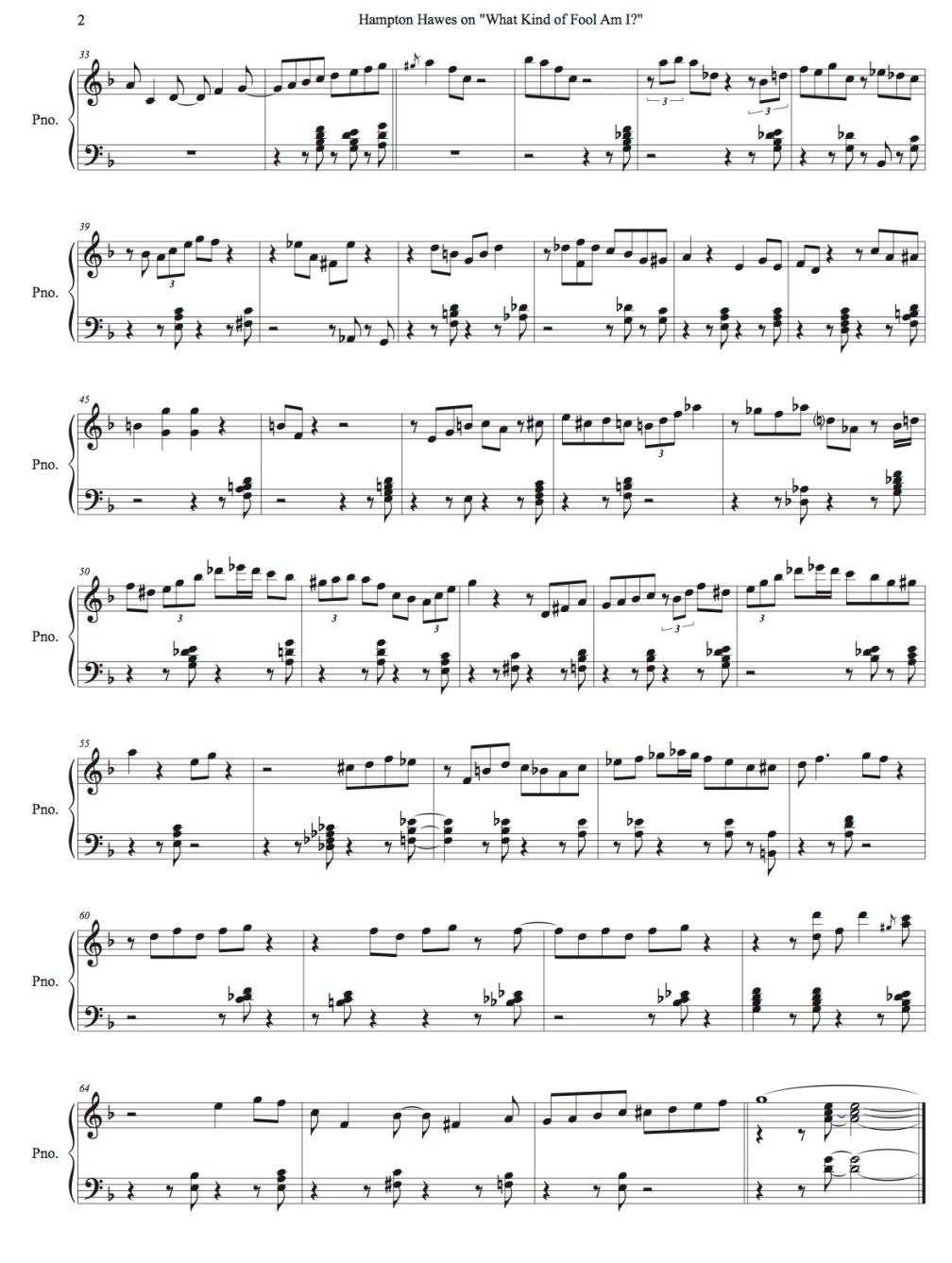

Here and Now was one of my best-loved albums when I was a teenager. Hawes tackles “the latest hits” with an ultra-modern rhythm section, Chuck Israels and Donald Bailey. On “What Kind of Fool Am I” Hawes makes up wonderful bebop melodies and drives his pulsating time through the middle of the chaos from the bass and drums. It’s doubtful Guaraldi could hang with Israel and Bailey here (VG was a notorious control freak about his rhythm sections).

(Related DTM: Hampton Hawes and the Low Blues and Drums and Cymbals by Donald Bailey.)

Jimmy Rowles is perhaps the ultimate refined taste for the truly discerning connoisseur of mainstream jazz piano. I never paid Rowles much attention until Mike Kanan made me keep relistening. Then one day I “got it,” and now I’m one of those nuts that collects Rowles LPs. So far, the two I think are most special are the solo album of Duke and Strayhorn (maybe the best Duke tribute album after Monk?) and The Special Magic of Jimmy Rowles with bassist Rusty Gilder.

I think Mike was also the one who made me aware of an extraordinary YouTube of Oscar Peterson hosting his show with Rowles as a guest.

The whole video is catnip for jazz piano fans. Oscar is so hip and respectful and the group with Ray Brown and Bobby Durham is so swinging. But I was especially struck by Rowles’s subtle chorus on “Our Delight.” Rowles almost doesn’t play like a pianist here: Most of his lines are more like an old-school tenor player, someone in-between Lester Young and Don Byas. That kind of “+1 higher octave smear” is definitely a way to get the piano to “talk” like a blues shouter or a brass person with a plunger.

Trivia: Jimmy Rowles was a studio musician in the 50s and 60s, and literally almost everyone has heard him play piano or electric piano on famous Henry Mancini hits. Yeah, that’s Jimmy Rowles! He was also the pianist on the first performance and recording of Stravinsky’s “Ebony Concerto” with Woody Herman. It’s not a virtuoso part, exactly, but it is certainly exposed. Yeah, that’s Jimmy Rowles!

—

Speaking of trivia, the biography Vince Guaraldi at the Piano by Derrick Bang is full of interesting stuff. The plunger mute has turned up already on this post, and it turns out the the first time the “talking adults of Charlie Brown” immortal “wah-wah” was introduced, it was played by jazz great Frank Rosolino. And the whistler on the hit Hugo Montenegro rendition of Morricone’s “The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly Theme” was Guaraldi’s uncle, Muzzy Marcellino. (At one point the relatives were both charting on the radio.)

Finally, Tom Harrell is featured on some 70s Peanuts specials. According to Tom’s own tweet, “Yours truly on trumpet solo and horn arrangement.” The vocalist here is none other than Vince Guaraldi.

Sunday Night in Bucharest

Thanksgiving for Sophia Rosoff

I started studying with Sophia Rosoff in 1996. It was a deep immersion. By November of that year I felt close enough to call her and wish her a happy Thanksgiving. She was devastated, for her husband Noah had passed the day before.

Sophia was a mystical creature. It only makes sense that she waited until exactly the same day Noah died, the day before Thanksgiving, to move on herself. She was 96.

The news is sad but also such a relief. For a few years Sophia had been battling various health woes. Still, she dispensed invaluable advice until the end, I’d hear tell of new students being stunned by her insight until just recently.

I was close to Sophia, For a time I was very close. When I started to write about music around 2005 I naturally thought about trying to profile my favorite teacher, but it didn’t feel quite right. Thankfully, my wife Sarah Deming took up the challenge and crafted a memorable essay that was printed in The Threepenny Review and found an online home here on DTM.

—

After I dropped out of college in 1993, I knew I should keep studying. I always liked Fred Hersch’s playing, especially that marvelous album Sarabande with Charlie Haden and Joey Baron, so I went to one of Fred’s gigs and got his number. Fred was the first person to show me anything about how to touch the piano, how to physically connect with what is essentially a block of wood. I worked hard with Fred. I was playing jazz but also found him extremely helpful when I brought in little European Classical pieces. At one point, at Fred’s suggestion, I played the first movement of Bach’s Italian Concerto not just in the given key of F major but in the keys of A major and D-flat major. He told me he got that invaluable exercise from Sophia Rosoff, and in time he sent me along to her. (Fred writes more about Sophia in his recent memoir, Good Things Happen Slowly.)

At the first lesson with Sophia I played Bach’s Fantasia and Fugue in A Minor (BWV 944) (not a great piece but good for the chops) and Chopin’s easy Nocturne in B. By the end of the lesson I was in love. Sophia’s understanding of music seemed positively unearthly. Soon I was one of the close group of students who met every week to play for each other. I heard staples of the repertoire like Schubert’s Wanderer Fantasy and Schumann’s Abegg Variations for the first time in a small room at the Diller-Quaile School of Music. This taught me there was no need to find a “best” recording of that canon. If you could just hear anyone play the pieces live, the message was legible.

Jazz musicians responded to Sophia because her emphasis was on rhythm. “Basic Emotional Rhythm” were her watchwords. In European Classical music you don’t play with a steady beat, and for jazzers that kind of perspective can be hard to learn. Sophia broke the music down into big beats so your heart and ear could follow the large-scale development of the sounds. She loved “outlining,” which in some ways bears a relationship to the wonderful theoretical work of Heinrich Schenker.

As a performer, it is your responsibility to project the emotional rhythm of any given composition even before you begin playing. I have never started a Bach or Chopin piece better than in Sophia’s apartment after her careful coaching. If I could play like that all the time, I’d be one of the greats.

Sophia was a Polish Jew. She moved to New York just in time to hear Rachmaninoff play in person. One of the most revealing lessons I had with her was on a group of Chopin mazurkas. She said, “Well, you have to figure out where you stamp your foot,” as if this was the most obvious thing in the world. According to Sophia, on some mazurkas you stamp on the second beat, on some the third. (Never on the downbeat, of course, that would make it a waltz.) Practical advice on how to create the right “feel” in European Classical music is usually hard to come by, but Sophia always had answers.

Sophia was also possessed of discerning genius in regards to piano technique. Her master was Abby Whiteside, and in fact Whiteside’s celebrated book Mastering the Chopin Etudes was prepared posthumously by Sophia and Joseph Prostakoff. The point is not use just the fingers to play the piano: One must use the big muscles to move the little ones. I know several pianists who were in pain before they worked with Sophia. Afterwards they had a new life at the keyboard.

Whiteside’s approach to technique shares much in common with that of Dorothy Taubman. These two powerful midcentury piano gurus didn’t like or learn from each other. As someone who has spent multiple years with disciples of both Whiteside and Taubman (my current teacher is John Bloomfield), I now think Whiteside understood the big picture best and Taubman understood the tiny final technical details best. However, either Whiteside or Taubman is an invaluable alternative to the old conservatory way of teaching of Carl Czerny and so many others, where you train your fingers to do the heavy lifting separately from the rest of the hard, arm, torso, back, and seat.

Sophia was a wonderful storyteller. In her heyday, New York City was a smaller town, and she met and heard everybody. Among other connections, her counterpoint teacher at Hunter College was Louise Talma. I myself met Talma shortly before she died in 1996 and was always interested in her music. Eventually I would help organize a concert of Talma, Vivian Fine, and Miriam Gideon at Weill Recital Hall with several fellow Rosoff students, John Kamitsuka, Hiroko Sasaki, Jeffrey Farrington, Gregg Kallor, and Jeremy Siskind. Talma, Fine, and Gideon were all Sophia’s friends and this concert had special meaning for everyone involved. (More recently I recorded the Fine and Gideon pieces for one of DTM’s academic essays.)

At the time of the concert I had been a diehard Rosoff student for over a decade, and sort of knew this was the “graduation exam.” Since then I have been much less in touch with Sophia and her circle, even though I always loved hearing about new students falling under her spell. A lot of the best younger jazz pianists have taken a lesson or two with Sophia, and a few like Mike Kanan and Jacob Sacks became noted emissaries of the Whiteside/Rosoff philosophy. I don’t think I can take all the credit for the mass pilgrimage to the apartment on 83rd street — in addition to Fred Hersch, Barry Harris, Tommy Flanagan, and Walter Bishop Jr. all consulted with Sophia (incredibly, even Ran Blake was a recent student!) — but I got there before most. If anyone asked me after 1995 about what I knew about music or what to study, I would always talk about Sophia Rosoff.

And now that she is gone, I will keep talking about Sophia Rosoff. Indeed, as is often the case, the passing of a great person brings their greatness into new focus. She was a rare and special soul, and everyone who knew her gives thanks.

Another Bebop Drummer Gone

New DTM page, about the late Ben Riley.

Thus Endeth Jazz

At times it becomes extremely hard to believe in the future of the music I love best.

Jordan Peele voices the Ghost of Duke Ellington in Big Mouth:

(Duke’s entrance is 34 seconds in.)

It’s all pretty offensive in a simian sort of way, but the terrible scatting/music cue really pushes all my buttons. If I were in charge of Ellington’s estate I’d be looking for a way to block this character.

(Get Out is a masterpiece, but: C’mon, Peele! You don’t have to like jazz, but you don’t have to hurt it, either.)

{Related DTM: Reverential Gesture. Related New Yorker Culture Desk: Duke Ellington, Bill Evans, and One Night in New York City.]

New Year: Do the Gig

Musée Mécanique, SF wharf

In 2018, I’ll be launching a new site, Do the G!g, which will anthologize and review NYC jazz. If you are interested in hearing more about it — especially if you are a musician who wants to try out writing about music — sign up for Floyd Camembert Reports, I’ll be emailing a full description of the site and the job openings by the end of the week.

https://tinyletter.com/ethaniverson

[longer pitch follows]

After 15 years of historically-focused output at Do the Math, it is time to branch out and attempt to help serve the current New York City jazz community. Basic coverage of the scene is at a dismal low while there are more excellent musicians than ever.

Do the G!g (a sister site run off the same WordPress account as Do the Math) will offer a splash page of listings. Suddenly free on a Wednesday night? Do the G!g will tell you where to go.

There will also be short and content-heavy reviews of performances written by a diverse group of young musicians committed to parsing the wildly eclectic current jazz scene. Reviews will be edited and sponsored by Ethan Iverson, but all judgments will be the writer’s own.

The reviews are not planned to be on the harsh “thumbs up” or “thumbs down” model. Simply reporting the repertoire and personnel is already valuable. Past that, reviewers for DTG will be quickly attempting to describe the content of the music. There’s so much going on, so many genres, so many references. Who is doing what and why?

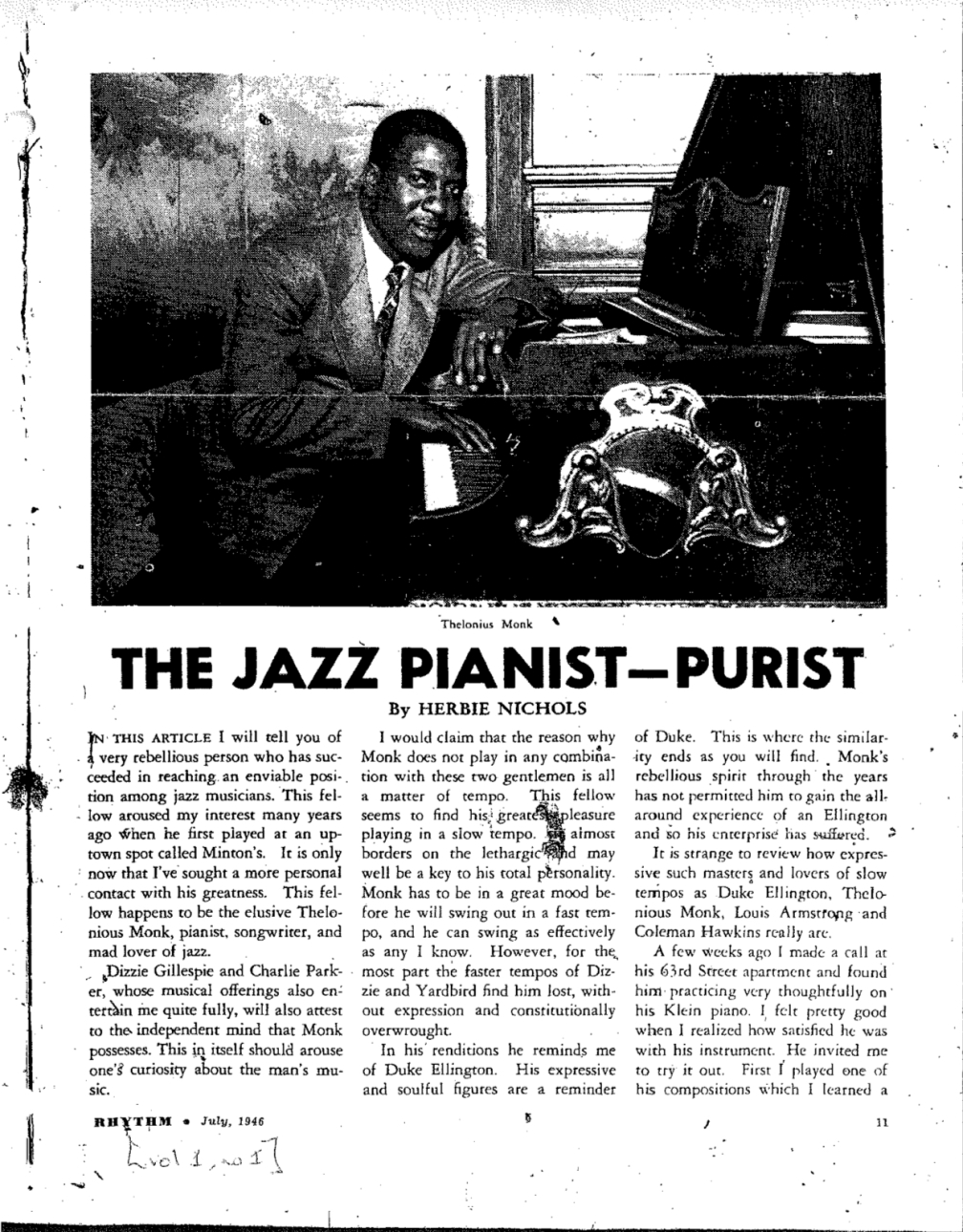

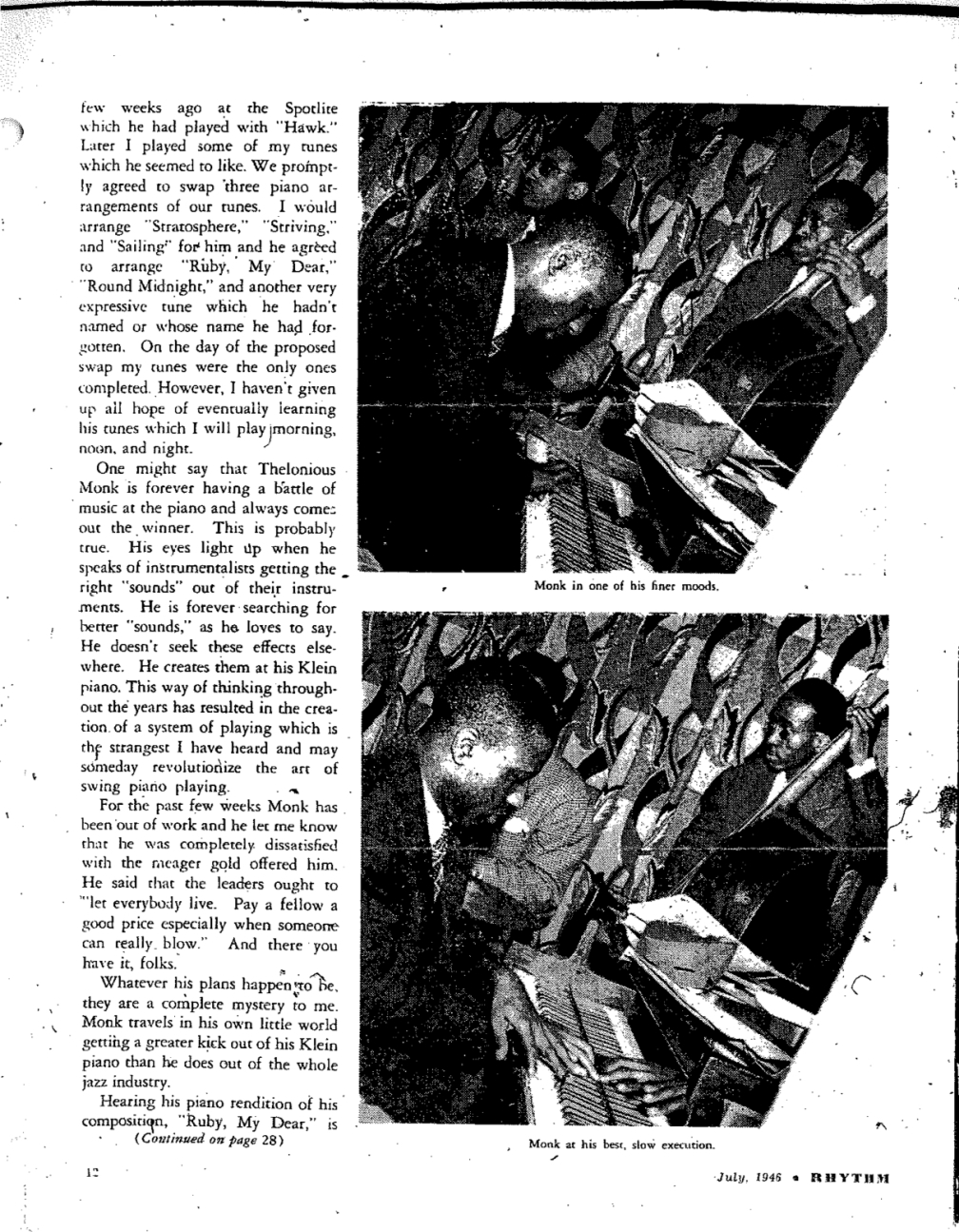

Herbie Nichols on Thelonious Monk

What a thrill! Rob van der Bliek, the author of the Thelonious Monk Reader, reached out after reading the big DTM overview and sent me the scarce 1946 article by Herbie Nichols for the Afro-American periodical Rhythm.

Here’s the scoop on the elusive Nichols piece on Monk from 1946: At the time I was gathering and putting together the material for The Thelonious Monk Reader in the late 1990s, there was confusion about Nichols’ piece, since he was quoted as saying in A.B. Spellman’s Four Lives in the Bebop Business that he wrote the profile for the Music Dial in 1946. I was at the Institute for Jazz Studies perusing their files and came across a photocopy of a column Nichols had written in 1944 for the Music Dial, in which he briefly mentions Monk as someone to watch out for, and after consulting with a number of people and having searched the remaining issues of the Music Dial, concluded that this was what he was referring to. Not so … As it turns out, years later both Mark Miller, who was working on a biography on Nichols, and Robin Kelley, who was working on his Monk biography, unearthed the 1946 article, but as it turned out it had been published in a magazine called Rhythm.

Amazing. I am overdue to read Mark Miller’s Herbie Nichols book and this glorious find is just the right push for me to do so. The book is available here.

The Most Bizarre of Operas

The Exterminating Angel by Thomas Adès proves that there is still room to shock, perplex, and provoke in the Grand tradition. I had been speculating that Adès was getting more and more “accessible” and “tonal” over the years, but his latest work is as brutally abstract as anything from him that I’ve heard.

The production has gotten excellent detailed reviews by Anthony Tommasini in the New York Times and Alex Ross in the New Yorker,

As every plot idea is a trope from fantastical fiction, The Exterminating Angel almost feels like a science-fiction opera. I loved the set. Hildegard Bechtler’s superb looming “Arc De Triomphe” put me in mind of the portal from the classic Star Trek episode, “The City on the Edge of Forever.”

—

Met Orchestra percussionist Jason Haaheim snuck us in to the pit at intermission.

The ondes Martenot played by Cynthia Millar is a key element in the score (and another science fiction reference):

Sam Budish slams the door:

More percussion.

I said, “More percussion!” (Is this the only Grand Opera with roto toms?)

My date, Rob Schwimmer, next to the big bells (also used in Tosca)

Jason plays the tympani.

The following note might seem a rather unfriendly item to start a score with, but Adès is a genius, so these radical meters (a way to notate nested partial triplets without changing tempo) are apparently acceptable — especially since Adès can sing, play, and conduct it all himself.

A moment of Jason’s tympani score with those meters in action. (Hard to sight-read!)

Very special thanks to Jason Haaheim.

Monk in Durham in NY Times

Good news! From Aaron Greenwald’s FB: “NYT’s Giovanni Russonello has a lengthy review of Duke Performances’ MONK@100, our celebration of Thelonious Monk’s centenary. Russonello has written a smart piece of criticism w/ exceptional photos by Justin Cook. I’m hugely proud of the festival & deeply indebted to all of the folks who worked tirelessly to pull it together.”