There’s been a lot of discussion about the politics of the movie Green Book. What about the music? I have a new essay about Don Shirley at the New Yorker Culture Desk.

Author Archives: Ethan Iverson

Four on the Floor

Guillaume Hazebrouck transcribed my choruses on “Bags Groove” from the album Philadelphia Beat. It’s quite thrilling to see the transcription done so well. I’ve been working on this style. I’m not all the way there yet, but this is definitely as good as I could do at the time of the 2014 recording. Ben Street and Tootie Heath sound wonderful, of course.

While I’m being egotistical: Hazebrouck sent me this the same day I published Theory of Harmony. Those events reinforced each other in a refreshing way. Whatever I’m playing here, it did not come out of a jazz textbook! (If you want a PDF of the finished Theory of Harmony, sign up for Transitional Technology and email me.)

Drummer Hyland Harris contributed a marvelous essay to Philadelphia Beat. Yesterday Hyland sent me a photo of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez visiting the Louis Armstrong House.

My own photoessay about visiting the Armstrong house is here.

Social Studies

NEW DTM PAGE, mostly for students, although music fans might like it as well: Theory of Harmony.

New in Books: Emily Bernard, Thomas Perry, Lawrence Block

The late Lorraine Gordon introduced me to the work of Emily Bernard one night at her house table at the Village Vanguard. Lorraine had a copy of Carl Van Vechten and the Harlem Renaissance: A Portrait in Black and White and was raving about it to anyone willing to listen. Van Vechten may not be a immediately familiar name in 2019, but in his heyday he was everywhere as a novelist, partier, photographer, and critic. Last fall, when Mark Turner told me he was working on material for a suite about James Weldon Johnson, I loaned him Bernard’s book. Mark was just as enthralled as I had been. This might be a new stage of major jazz musicians reckoning directly with that era of the history (at the Vanguard last November, Jason Moran explored James Reece Europe the week before Mark brought in James Weldon Johnson), and someone like Bernard is a perfect guide to seeing the bigger picture of race and culture in America.

I’ve promoted Bernard on DTM; I’ve also met her and her husband, John Gennari (who writes about jazz) in person. Naturally, I feel extra pleased about how Bernard’s new book, Black is the Body: Stories from My Grandmother’s Time, My Mother’s Time, and Mine, has been rapturously received by the world at large. (Full disclosure: I get a lovely namecheck in the acknowledgments.) The raves are everywhere, including Maureen Corrigan/NPR and Kirkus Review. The book went into a second printing the same week of release.

Bernard’s lessons keep reverberating in fresh ways. Originally when seen online, “Teaching the N-Word” was a searing revelation. Now collected in Black is the Body, “Teaching the N-Word” has attained the status of an honored classic. Of the new material, I was especially bowled over by the frank and occasionally hilarious examination of living in Vermont in “People Like Me.”

Now that she’s becoming a more visible literary presence, it will be interesting to see what Bernard writes about next. The latest essay at LitHub, “But What Will Your Daughters Think?” suggests the meditative and honest way Bernard might respond to being widely read.

—

Thomas Perry has written 26 thrillers. The latest is The Burglar.

Perry excels at describing people at work. Professionals. Men and women who get the job done through the steady and methodical application of skilled labor. Our current specialist is Elle Stowell, a cat burglar who inadvertently ends up as a kind of avenging angel. The book has an unusually slow build, the threads take some time to gather, I was frankly skeptical of the initial sensational murder and “hip young Los Angeles” characters…but eventually the plot turns out to be one of Perry’s most surprising conceits. Indeed, I believe the central moneymaking scam is unprecedented in the literature.

I liked Perry’s previous half-dozen entries, but had also wondered if the author had hit a kind of plateau. The Burglar gave me the kind of breathless wonder I last experienced after The Informant.

—

Mr. Lawrence Block can still shock! The Matt Scudder saga has turned into a decades-long examination of societal mores. The new novella A Time to Scatter Stones is the latest chapter in what is almost certainly the greatest detective series extant. Block’s spare sentences remain wonderful, especially when they recount the humorous dialogue between Scudder and his wife Elaine. I could say more about this story but I’d prefer everyone else’s jaw to drop just as much as mine did. Don’t read the reviews first.

(Full disclosure: There’s an amusing mention of Scudder and Elaine buying a Bad Plus shirt at the Vanguard. This is at least the second time TBP has made it into a crime story; the first was in Duane Swierczynski’s Severance Package. At any rate, getting mentioned more or less simultaneously in books by Emily Bernard and Lawrence Block is a wonderful birthday present!)

George Cables is Back!

Last night I was lucky and caught the second set of the George Cables trio with Dezron Douglas and Victor Lewis at the Vanguard.

Mr. Cables was on fire! Afterwards he told me that he’s been practicing more than ever. It sounded like it. Take no prisoners!

In March 2018 Cables had his left leg amputated. It was a dramatic story, we were worried about his future, yet the musician hitting last night at the club is still one of the greatest NYC jazz pianists.

The set included his first tune, a Bird blues with a bridge called “Happiness,” and two recent pieces, the ultra-modern (nearly prog-rock) fantasia “The Mystery of Monifa Brown” and the heartfelt tribute “Farewell Mulgrew.”

Cables and Victor Lewis go way back. Naturally, Lewis sounded terrific as well, a big beat and every note both authentic and personal. Of the straight ahead masters, only Victor has a second snare to the side for timbale effects. Dezron Douglas fit right in with taste and swag.

They are at the club through Sunday.

(DTM: Interview with George Cables)

This Week at the Village Vanguard

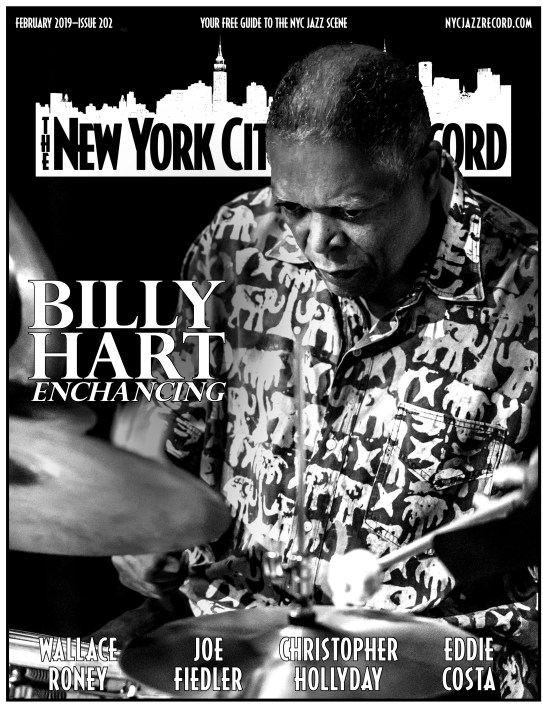

The Billy Hart quartet with Mark Turner, Ben Street, and me, tonight through Sunday.

Notes from an Autobiography

Floyd Camembert Reports is dead, long live Transitional Technology. In the early days of the old newsletter, I put in a few autobiographical bits, which I’ll post again here:

—

I take kind of a personal interest in Scientology because my first job in New York in the fall of 1991 was with a group of Scientologists. Fresh of the haytruck from Wisconsin, I landed in a cult.

Actually “cult” makes it sound worse than it was. Everyone in the National Improvisational Theater was very nice, and some of the actors were extremely talented. Their show was every Monday night in Chelsea and it was improv comedy: skits, songs, and lots of audience participation. I learned a lot. If you’ve heard me improvise a song accompaniment for Reid at a TBP gig, that’s the sort of thing I first did with NIT.

NIT wasn’t that successful, the audiences were smallish, my pay was $20 for a gig. It was good money for me in those days, my main food source was a dozen day-old bagels for a dollar.

When I started at NIT I didn’t know about their connection to the religion. After a few months they revealed the truth and placed a fair amount of pressure on me to join. I didn’t want to become a Scientologist, but I wanted to keep playing the gig.

One of our one-off performances was at the midtown Celebrity Centre where I got tested by an E-meter. I recall this being one of the best gigs, with a nice-sized audience and lots of laughs. There were fancy photos of Celebrity Scientologists on the walls, including a big one of Chick Corea.

A few weeks later NIT offices received a letter to me from Corea. Or maybe it wasn’t from him, maybe it was from a minion, how would I know? At any rate it was a handwritten letter saying that he had heard that I was talented and that he was looking forward to meeting me someday, maybe on a Celebrity Cruise. Signed, “Chick Corea.”

I was 19…for about an hour I was like, “Wow, Chick Corea wants to hear me play!” before realizing that he just wanted to help get me in the church.

I left the NIT soon after, it was just too weird.

When I’ve had to meet Chick professionally over the years, I keep my distance, worried that he’ll ask me to join Scientology again.

———

During the 90’s I worked frequently as a dance class accompanist. Eventually I ended up trying out for Mark Morris. Mark is easy to play class for: he’s very energetic and fun, and all of the Morris dancers have good rhythm.

Eventually Mark asked me not to play just class but be the rehearsal pianist for a full Morris production of Rameau’s Plateé. I’d never done anything like that but how hard could it be? Just read a few bars of baroque music over and over at a time, right?

At the first rehearsal, nothing much happened except Mark playing everybody the complete opera on the stereo. It was nice music, and I followed along with the score, relieved that it wasn’t going to be too hard.

To my surprise, when I checked something against the piano, the piano’s A was more like an A flat on the record. I had heard that baroque performance used a lower tuning than modern A=440, but this was my first time encountering it in a professional situation.

At the end, I went up to ask Mark about the discrepancy between piano and the recording. He was changing, and I accidentally caught him right in between dance clothes and street clothes. Indeed, he was entirely naked when he got interested in my question, stopped doing anything else, and offered a learned and extended disquisition on 440, 415, and the varieties of contemporary interpretation of baroque pitch.

I listened carefully, and at the end said, “You know, Mark, I’ve never discussed intonation with a naked man before.”

Mark gave me a wicked grin and replied, “Stick around, baby!”

Which I did: Not long after the premiere of Plateé, I became Mark’s music director for over five years.

—

RIP Harvey Lichtenstein. I performed at his 1999 farewell party “The Harvey Gala” with Mark Morris. It was amazing night of stars including Paul Simon, Philip Glass, and Lou Reed, and there I was listed in the program: Zwei Harveytänze: choreography and performance, Mark Morris; music: Raskin (“Laura”), arr. by Ethan Iverson, Iverson (“Flatbush stomp”); music performed by Iverson. (My piece “Flatbush Stomp” was kind of a Monkish boogie woogie.)

I remember a lot about this event, even odd details about the people at the podium. When André Gregory (My Dinner with André) got up to take a turn as MC, he spent the first ten minutes off on a tangent about the time he wrote Audrey Hepburn a fan letter and she wrote him back. This made no sense in the context of the evening as a whole, maybe he was drunk. Then when Harvey himself appeared at the podium near the end he wheezed, coughed and huffed for a few long minutes before being able to speak; we were worried he was going to keel over.

As far as the actual performances: the most shocking thing during “The Harvey Gala” was just how loud Lou Reed and his band were. They horrified the whole audience except the true believers. I was also surprised how many wrong notes Philip Glass played in his piano etudes. (It’s easy to tell when there’s a wrong note in that repertoire.) Dave Douglas offered an all-star group backing Trisha Brown that night, but I remember better a full Brown/Douglas dance at Joyce the previous season, a very cool show. For me the personal highlight of the gala was watching Steve Gadd play with Paul Simon. I see from the list of performers at WorldCat that Chris Botti was in the horn section.

—

RIP Clyde Stubblefield. The fabulous Funky Drummer inspired James Brown on so many hits and had an unexpected second act when his beats were frequently sampled by hip-hop artists decades later.

I crossed paths with Stubblefield once as a youngster.

Wisconsin jazz violinist Randy Sabien hired me a few times when I was a freshman or sophomore in high school. Sabien also played at Menomonie High with his regular quartet that included Stubblefield, who at that time was a jobbing musician living in Madison doing whatever paid (including, rumor had it, country music gigs). This was maybe 1988: I knew who Stubblefield was from James Brown but his fame as “the man who gave hip-hop its syncopation” was still slightly in the future (or if it was already happening I hadn’t heard about it yet).

Even more than the Harvey gala, I wish I could go back and hear that little high school auditorium gig again. What did Stubblefield sound like in that group, which was not “funk” but “jazz?” I remember having a really positive impression. As far as I know he’s not on any straight-ahead records. However, his famous 60s funk tracks with Brown were definitely on a small jazz kit and his touch was nice and light (at least compared to 70s funk drummers) so he was suited to be jazz drummer as well. At the least, Stubblefield was surely one of the greatest jazz drummers in Wisconsin at that time — which, admittedly, is not saying all that much. Still. Clyde Stubblefield. Damn!

Since I had played a bit with Sabien, he generously asked me to sit in on a blues. I can’t remember who else was in the band, I was just paying attention to Stubblefield.

So that is how it came to be that Clyde Stubblefield was the first Afro-American professional musician I shared a bandstand with, for one tune when I couldn’t have possibly been more green. Not only that, he gifted me with a little kick in the pants. For my solo, he and the bassist doubled the tempo. They clearly talked about it in advance: “When it’s the kid’s turn to play, let’s go twice as fast.” I stayed calm, played my Monk-type things fine and didn’t lose the form. Afterwards I remember Stubblefield gave me a smile.

A great lesson: When you go up to sit in, know that the band might not take it easy on you.

—

By the end of high school my constant imitation was too much. Thelonious Monk himself came to me in a dream and told me to quit the charade. Monk, John Coltrane, and Art Blakey (who had just passed) came back from the dead to play one last trio gig. Monk played many more notes than his living style, Coltrane many fewer notes than his living style, and Blakey was lighter and less theatrical, more like Billy Higgins. It was a great gig! (They sure didn’t need a bass player.) For the encore, Monk came out and played one of his utterly magnificent solo ballads, a cross between a hymn and sentimental love letter, stamped in burnished gold with his trademark acidic harmony. I was so moved by the encore I wept and went backstage. When I found Monk I interrupted him with his friends and begged, “How do you do that?”

He looked at me, his face nothing but irritation, perhaps even contempt. “You just need to go to church,” he curtly explained before turning back to his crew.

When I woke up, it was clear that the message was, “Better try to be yourself, because you will never be Monk.”

—

If you want to support Do the Gig and Do the Math and also get updates about gigs, masterclasses, and new DTM posts, subscribe to Transitional Technology.

Ethan Iverson’s Home Page

Greetings! Thanks for stopping by! This WordPress site is rarely updated. To keep up with my current events including articles and gigs, subscribe to my newsletter, Transitional Technology. (Sign-up is free.)

Twitter is my evil social media drug of choice, where I post frequently.

At the moment you are looking at Do the Math, a blog (but really more like an internet magazine) that began in 2004 and runs well over a million words.

The most significant DTM posts are “pages,” organized by topic:

Interviews: Over 40 discussions, mostly with musicians: Billy Hart, Ron Carter, Keith Jarrett, Marc-André Hamelin, Carla Bley, Wynton Marsalis, many others.

Consult the Manual: Lessons, mainly material written for my piano students at New England Conservatory of Music.

Rhythm and Blues: Jazz music essays about McCoy Tyner, Thelonious Monk, Ornette Coleman, Geri Allen, Bud Powell, Lester Young, many others.

Sonatas and Études: Classical music essays about Glenn Gould, Igor Stravinsky, a few others.

Newgate Callendar: Crime fiction essays about Donald E. Westlake, Charles Willeford, a few others.

Photo credit above: Keith Major.

Again, if you want to read my current writing and also get updates about gigs and masterclasses, please subscribe to Transitional Technology.

Fridley, Here I Come

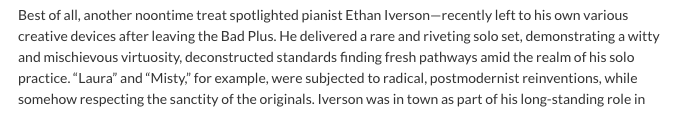

Back to the Dunsmore Room at Crooners on Tuesday. Solo piano, standards and originals.

This gives me the opportunity to link to the nice review Josef Woodard gave my solo concert last summer at Umbria.

Deep Song

In New York City we are currently in the middle of Winter Jazz Fest, a time when the greatest musicians near and far swarm the city and play short sets in dozens of venues. This year the explicit mandate is “Jazz and Social Justice,” a phrase that has become popular since the last presidential election.

If “Jazz and Social Justice” has a theme song, it surely would be John Coltrane’s “Alabama,” a wonderful track originally included on Live at Birdland. Wikipedia claims that the composition, “…Was written in response to the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing on September 15, 1963, an attack by the Ku Klux Klan in Birmingham, Alabama that killed four African-American girls.”

Wikipedia is probably not wrong, but Coltrane wasn’t overwhelmingly explicit. In the original liner notes, Leroi Jones (later Amiri Baraka) writes:

“Bob Thiele asked Trane if the title ‘had any significance to today’s problems.’ I suppose he meant literally. Coltrane answered, ‘It represents, musically, something that I saw down there translated into music from inside me.’ Which is to say, Listen.”

Reportedly the other members of Coltrane’s quartet did not know the title or the meaning of “Alabama” at the time of tracking. The only other time Coltrane played the piece seems to have been on the television show Jazz Casual, an occasion where Coltrane did not address the audience.

However, the point of just how much Coltrane himself tied the bombing to his composition is mostly moot, for every single glorious note recorded together by Coltrane, McCoy Tyner, Jimmy Garrison, and Elvin Jones strikes a blow for social justice. The story behind “Alabama” is actually told in any Coltrane performance. Whether they read about “Alabama” or not, any John Coltrane fan has a chance to embrace multiplicity and learn about American history simply by listening to his records.

Coltrane was sympathetic to Baraka and other civil rights leaders; he also supported the best players of ‘60s avant-garde jazz, some of which was explicitly tethered to civil rights protest. In 1965 a concert benefiting the Black Arts Repertory Theatre/School was held at New York’s Village Gate. Baraka was deeply involved in the concert and then wrote the notes for the resultant album, The New Wave In Jazz.

All the musicians performing at Gate that night were fabulous, but Coltrane was the biggest star, and only his picture is on the cover of the LP. Coltrane could have played anything he wanted, but he chose to introduce a marvelous rendition of “Nature Boy,” a standard by Eden Ahbez (a real oddball in the in the history of American music) made famous by Nat King Cole.

The lyric to “Nature Boy” concludes, “The greatest thing you’ll ever learn, is just to love and be loved in return.”