Happy birthday to me!

50 is a substantial number.

One way to measure: I was born three years before the American Bicentennial, so now I have lived through almost one-fifth of United States history.

Another way to measure: My father drank himself to death four days after turning 50.

Drummers by decade:

Billy Hart born 1940

Victor Lewis born 1950

Jeff Watts born 1960

Eric McPherson born 1970

Kendrick Scott born 1980

Hyland Harris looked at this list and commented, “Ten years is a long time.”

2023 has a lot of jazz centennials. (Complete list here.)

Milt Jackson would have been 100 on January 1. Jack DeJohnette told me he was very impressed with Opus De Jazz, Jackson’s 1955 Savoy session, because of how swinging Kenny Clarke was on that date. “The whole groove on that album is incredible,” Jack said.

Tomorrow, February 12, Mel Powell would have been 100. The Powell overview at DTM is one my most esoteric essays.

The next major commission is symphonic in nature, so I’m reading orchestration books and wrestling with how to deploy forces. (A hint of what the commission entails is teased at this tweet.)

At a social event this past December I asked Missy Mazzoli to give me some advice. “Write first violins and flutes above the staff,” she said. Good advice.

There are not too many bass concertos, and even fewer of those bass concertos are any good. Mazzoli’s Dark with Excessive Bright (Concerto for Contrabass and String Orchestra) is truly unexpected, almost as if the soloist is a gritty bard in a Tom Waits mode. I am eagerly awaiting the new recording on BIS for Mazzoli’s forthcoming album of the same name.

Also new and for string orchestra: Thomas Adès’s Shanty – Over the Sea. Bluesy, surreal, seven minutes, perfect.

Both these pieces (the older recording of Dark with Excessive Bright and Shanty – Over the Sea) can be heard as singles streaming from the Australian Chamber Orchestra as part of their excellent ACO Originals series.

When I was starting to write for big band, Tom Myron came up to me at a gig and told me seriously, “Write the trombone above the tenor sax.” Good advice.

Myron is a subtle and refined composer (try his sensational Violin Concerto No. 2) who — unlike many other fine contemporary composers — also really understands “pops” arranging for the symphony. When I asked Tom to vet my work before I hand it in, he immediately gave me an orchestration reading list and shared a few recordings I hadn’t heard before. In each case these works are not just great in terms of style and idea, but the orchestration is simply marvelous.

Walton: Symphony No. 1

Boris Blacher: Orchestral Variations on a Theme of Paganini

Shostakovich: Symphony no. 9

Honegger: Symphony No. 4 “Deliciae Basilenses”

I joked to Tom that Honegger 4 sounded like Claus Ogerman. He responded, “Maybe that’s why I like it so much.”

As part of my research into jazz (or “pops”) made with conventional orchestra, I purchased the recording of Ogerman’s Symphonic Dances. Without a rhythm section or a star soloist I am not quite sure that Ogerman’s middle-of-the-road argument carries the day.

While many of my peers (such as Mark Turner and Ben Street) fervently admire the Ogerman/Michael Brecker collaboration Cityscape, my own favorite “serious” Ogerman remains Symbiosis for Bill Evans, especially the long “perpetual motion” soli for massed horns over a quasi-Brazilian rhythm section. That’s some unique music! Ogerman said he loved Max Reger, and one can sort of see that kind of Teutonic chromatic contrapuntal logic at work in this unpredictable 5-part writing.

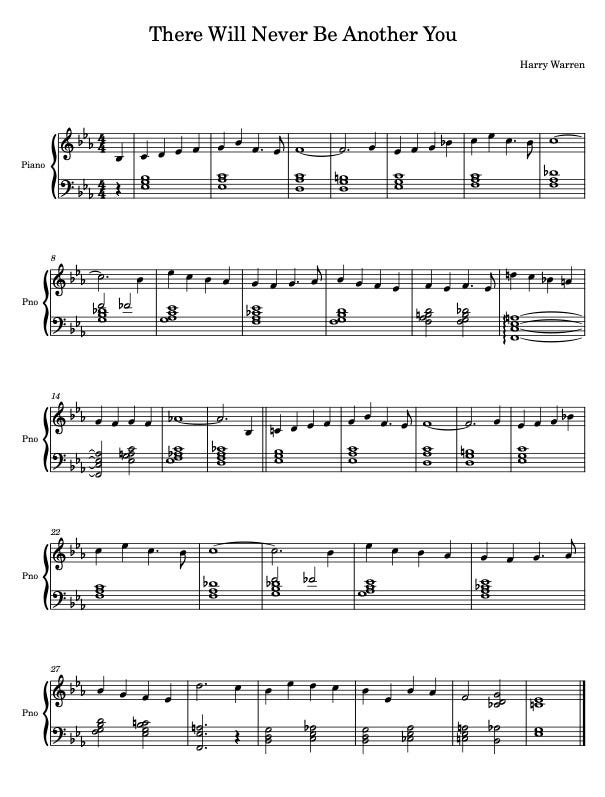

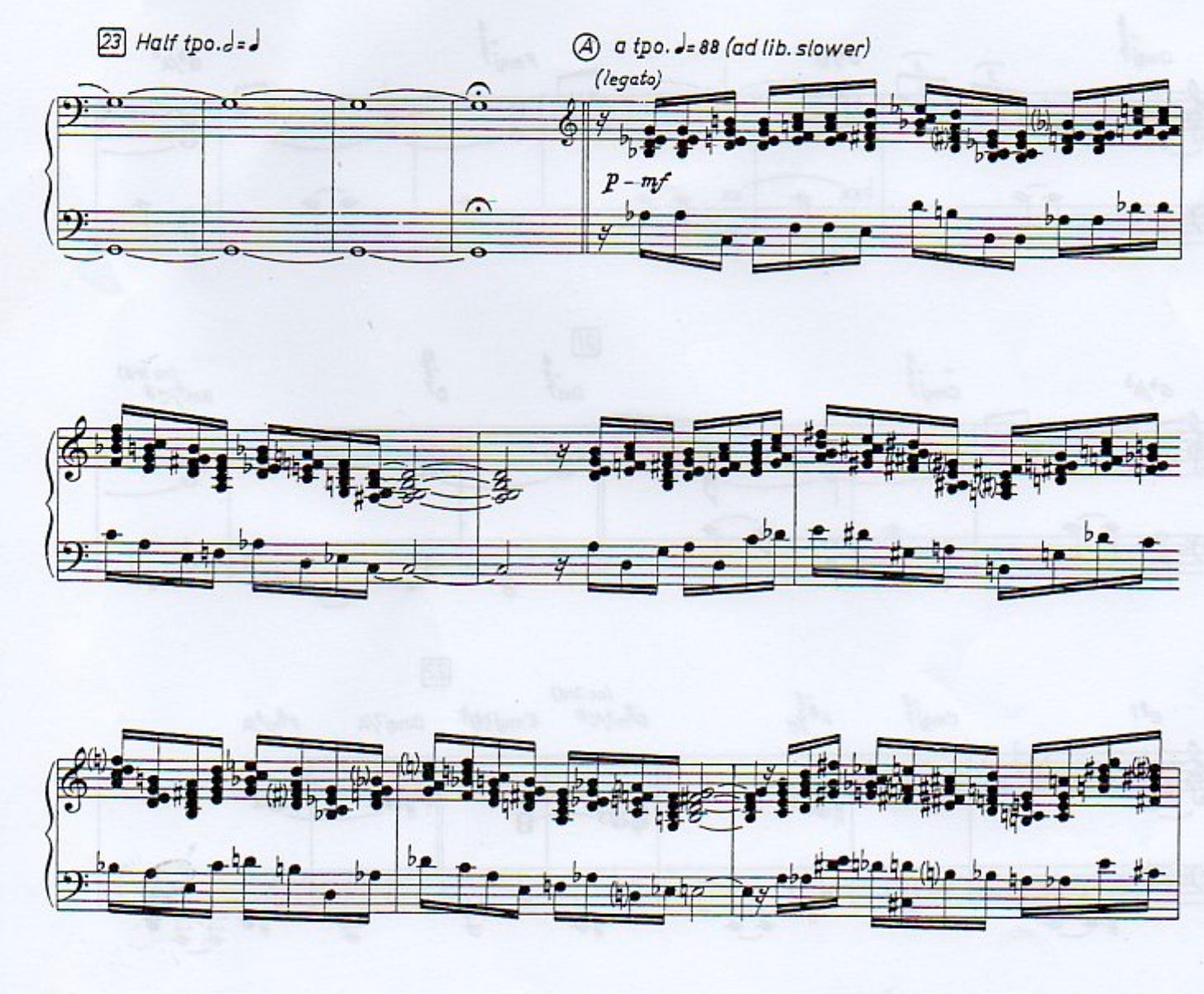

From the condensed score of Symbiosis:

Bernstein’s Candide Overture and Shostakovich’s Festive Overture were two of the more familiar items recommended by Tom; they are both also somewhat close to a “pops” style. Having looked at the books and fooled around with my own sketches, I now see these two warhorses in a completely new way.

Also in our discussion, with my own comments:

Roy Harris: Symphony No. 3. Fascinating work and a key to the “Americana” concert style.

Bartók: Concerto for Orchestra, Lutoslawski: Concerto for Orchestra. I prefer the Lutoslawski, which features the greatest passacaglia I’ve ever encountered.

Milhaud: La création du monde. One of the first and still one of the best “jazz” pieces for “classical” musicians, although now I know enough to complain about some of the awkward orchestration.

William Schuman: Symphony no. 8. I learned about this masterwork from Kyle Gann, who has a long history with Schuman. At some point I’d like to listen to all of Schuman’s symphonies with the scores in hand…

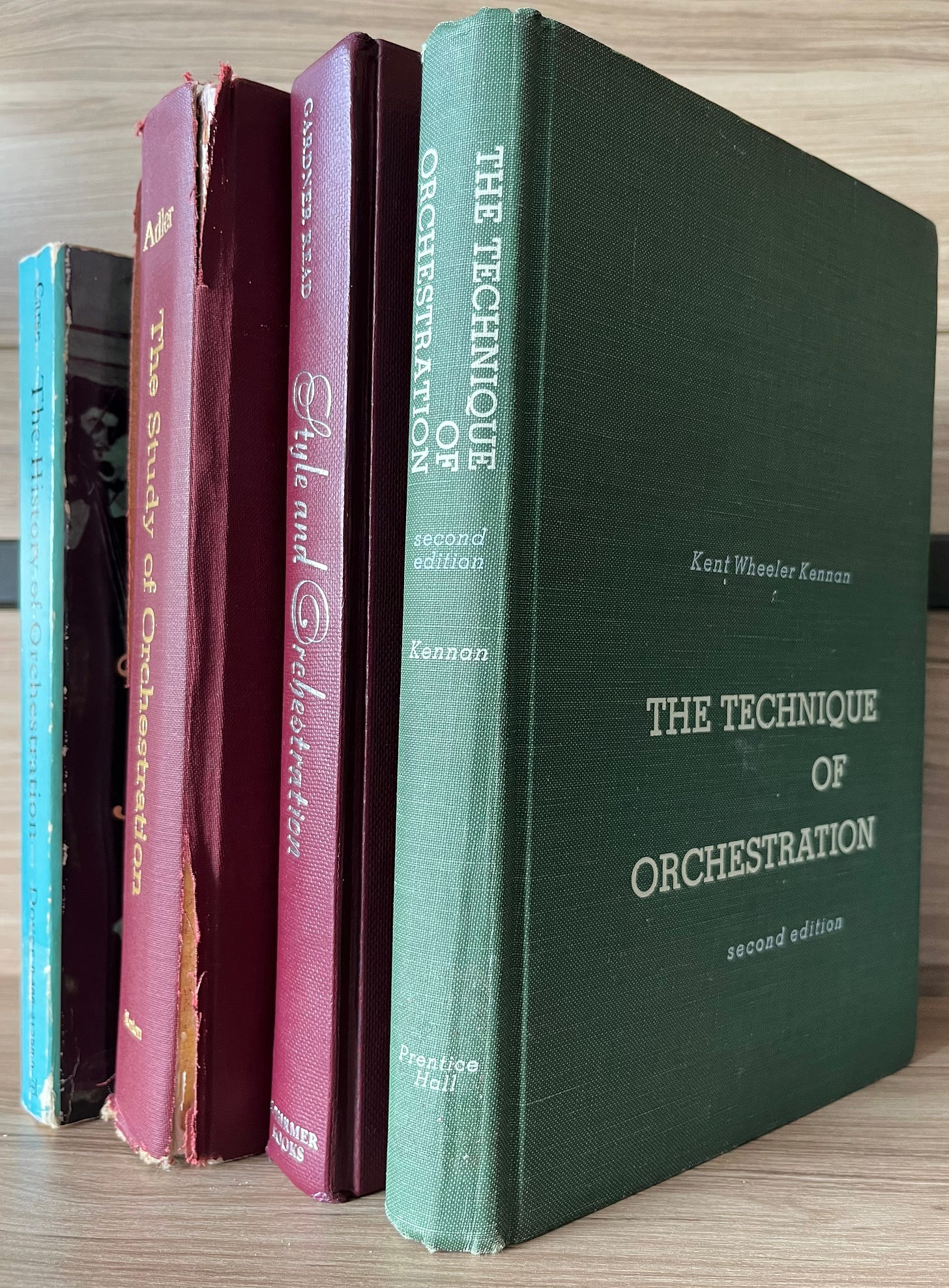

Kent Kennan is direct, excellent, and easy to read; Samuel Adler is also valuable but perhaps a little less fun. Gardner Read moves right along but my favorite is Adam Carse. The History of Orchestration is almost a century old (published 1925) but I just love the way Carse writes about the music.

On Gabrieli:

The addition of an extra choir or two does not dismay this inveterate polyphonist, nor does it compel him to resort to the doubling of vocal parts by instrumental voices. His desire is a full and rich volume of tone; co-operation rather than individualism is his instrumental creed, and an impartial distribution of material his only resource.

On Monteverdi:

Perhaps the most remarkable of the few surviving works by Monteverde is his Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda, produced in 1624 but not printed till 1638. In this piece the composer presents two new and genuinely orchestral effects. Both are now the common property of the meanest orchestral composer and arranger, but early in the seventeenth century cannot have been other than startling or even bewildering novelties to ears unaccustomed to anything but a polyphonic movement of parts. Even at that time everybody must have heard string players twang the strings of their instruments with the fingers, but only Monteverde thought of using this as an orchestral effect. While the fight between Tancredi and Clorinda is in progress he directs the players to discard their bows and to strike the strings with two fingers, in short, he creates the pizzicato effect….

…The above passage follows one which contains what is no doubt the germ of the modern tremolo. The power to reiterate any note at almost unlimited speed is a feature of bowed-string-instrument playing which is shared by neither wind nor keyboard-instruments.

On Gluck:

…It is impossible to disassociate from his orchestration the principles of a composer whose artistic creed embraced such significant views as those set forth in the preface to Alceste: “that the instruments ought to be introduced in proportion to the degree of interest and passion in the words”; that “instruments are to be employed not according to the dexterity of the players, but according to the dramatic propriety of their tone.” Thus, dramatic fitness alone was to govern his use of instruments: the effect of the orchestra was to be true to the situation on the stage…

…It is hardly surprising to find that a composer who acknowledged no law but the law of dramatic truth should orchestrate his operas in a manner which broke many links with the past….

Carse dates himself by subtly criticizing the orchestrations of Bach and Handel. But, then again, the early music movement that re-invigorated Baroque performance practice was still several decades away. As with my researches into piano music, I enjoy reading the history from commentators and practitioners who learned their craft at the end of the 19th century and were more or less untouched by the stormy currents of the 20th.

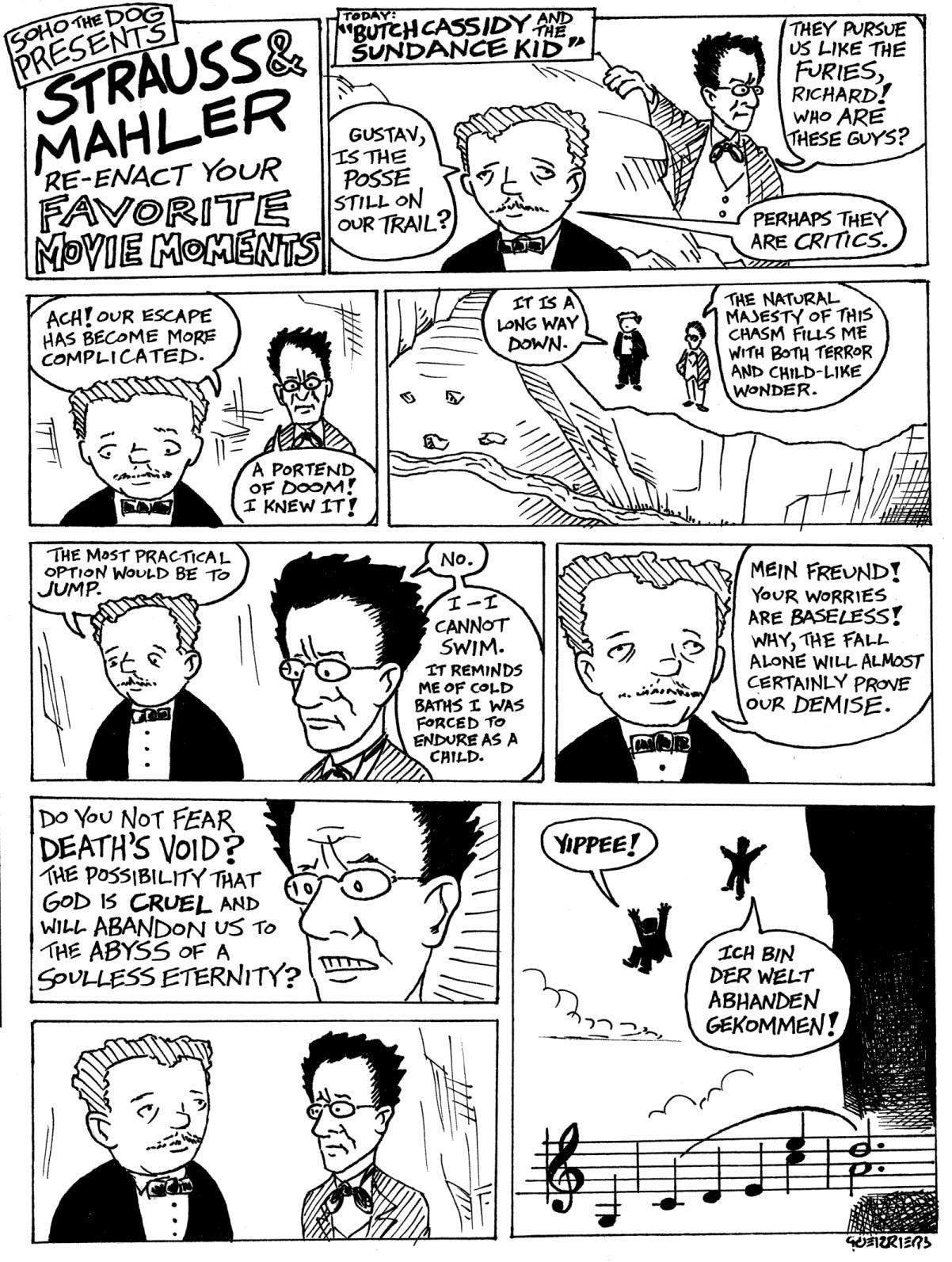

Amusingly, Carse ranks Elgar with Strauss and Debussy. Carse also documents that 1925-era historical moment when Mahler was considered far less successful than Strauss (although Carse himself admires both.)

The pairing of “Strauss and Mahler” reminds me of Matthew Guerrieri’s series of cartoons on his Soho the Dog website. Yesterday was a Guerrieri festival on DTM…why not conclude today’s post with my favorite? Seems somehow appropriate for turning 50…