Last week we lost a key musician from the ’70s and ’80s as well as one of the most significant jazz and improvising cellists. Abdul Wadud was obviously inspired by the ’60s avant-garde, but he also had a thorough grounding in European classical music and could groove like a funk bassist.

There are two interviews hosted at the Point of Departure site, “Knocking Down Barriers” from 1980 and “By Myself” from 2014.

Julius Hemphill, Dogon A.D. (1972) with Baikida Carroll and Phillip Wilson.

All tracks by Hemphill.

“Dogon A.D.” Julius Hemphill was part bluesman, part modernist, and part trickster. A natural composer, he left us hundreds of pieces for all sorts of configurations and contexts, none more durable than the extended “Dogon A.D.,” from which a whole world of modern jazz flows, partly through the influential tributary of Tim Berne (who placed Hank Roberts in the Abdul Wadud role). It’s the first tune on Hemphill’s first album, but he knew just what he was doing, including subbing out the expected bass chair for Wadud’s funky arco strut. Drummer Phillip Wilson (who gigged with commercial groups like the Paul Butterfield Blues Band as well as avant cats, see the DTM interview with David Sanborn) holds the 11/8 right in the pocket as Hemphill and Carroll preach their stories. A legendary track.

“Rites” After the focus of “Dogon,” “Rites” is a chaotic barnburner, where a tight melody with a touch of bebop opens the door to collective improvisation. Wilson is just as superb playing the free chatter as the tight 11/8 groove, while the whole texture is essentially defined by Wadud’s scales, glisses, and shrieks. Near the end of the improv, Wadud groans out a sliding pedal point on fifths, a bagpipe gone wrong.

“The Painter” For the other long track on the original LP, Hemphill plays flute, Carroll is muted, and Wadud strums his cello like a guitar. There’s something of an innocent fantasy to this piece, even (strange as it may sound) a feel not far from ’60’s folk-rock. Wilson’s brushwork keeps a loose groove with the “guitar” under the horns. It’s impossible to imagine any other cellist making this work so well.

(bonus track from same session with Hamiet Bluiett added on baritone sax)

“The Hard Blues” Look out! Phillip Wilson with a nasty backbeat and the horns in full funky attitude. Bluiett has the low notes while Wadud comments pizzicato in a bluesy style. A brief Stravinsky fanfare leads into a hint of bop, but the solos stay in the slow strut. Wadud keeps the vibe going, never leaving the basic idea too far behind, although he certainly varies it a bit to go alongside the changing intensity of the horns and drums. Hemphill plays in truly inspired fashion, but everyone else also sounds just great. There’s at least one awkward edit, but the whole Dogon session remains essential.

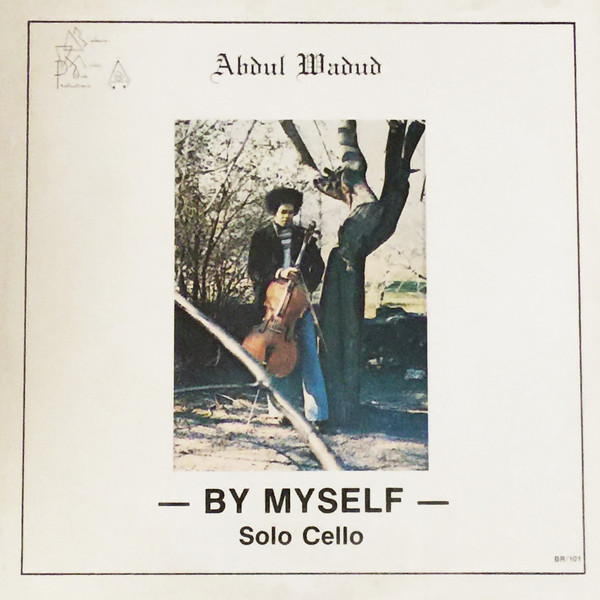

Abdul Wadud, By Myself (1977).

All tracks by Wadud.

“Oasis” There must be a few other solo cello jazz/improv records out there, but the masterpiece is surely By Myself, which is actually one of the most friendly and listenable of all avant jazz solo recitals on any instrument. “Oasis” is pizzicato. After a few disjointed melodies clear the air, Wadud settles into tonal strummed chords. It sort of has the friendly atmosphere of folk music, yet at the same time the sounds are clearly organized in intellectual terms. A pop bass line is the final answer, until…

“Kaleidoscope” Turns the heat up with pure expressionist arco frenzy. Ornette Coleman’s violin may have been the first time this kind noisy string aesthetic got an airing, but of course Wadud has more basic command of the instrument. The shrieks turn into bluesy pizzicato chords; in time, this track also ends with a pop bass line.

“Camille” Time for glorious song, arco, long, high, and deep. The pizz returns, a soulful vamp-like structure, with perhaps a hint of flamenco. Fade out. Recently, Tomeka Reid suggested that “Camille” would be “Five Minutes to Make You Love the Cello” in the New York Times.

“Expansions” Side two begins with fast pizzicato, almost like a lunatic walking bass line. Fractured phrasing works with and against the open strings. Arco returns, the “expansions” of the title now mean pulverized material and leaps forward into nothingness. The fast pizz bass of the beginning returns to “walk” it out.

“In A Breeze” More folksong, a kind of sentimental ballad heard on a back porch somewhere down South. Go ahead, Abdul Wadud.

“Happiness” “In a Breeze” was nothing but pretty, but “Happiness” begins with arco high screech. Soon a low melody contextualizes the dissonance. I’m not exactly sure how Wadud plays the percussive third section, it might be bouncing the bow on the strings. For the coda, a pizzicato folk melody dances high up on the instrument, first unaccompanied, then with Wadud’s trademark strum.

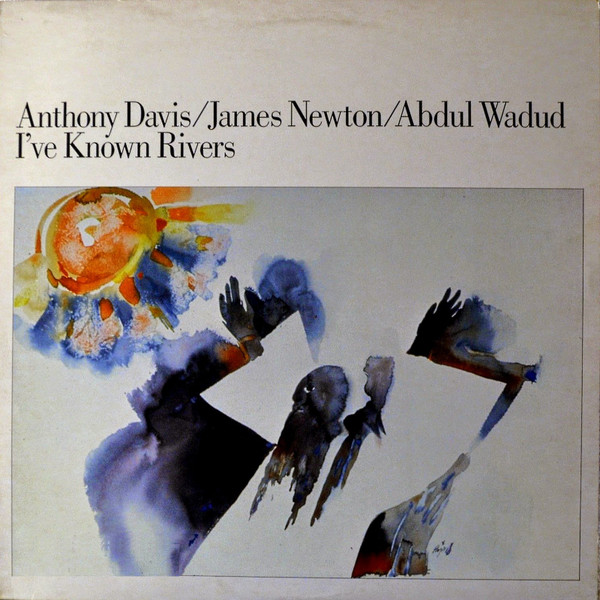

Anthony Davis, James Newton, and Abdul Wadud, I’ve Known Rivers (1982).

“Juneteenth” (Newton) While Dogon A.D. and By Myself were self-produced for indie labels, I’ve Known Rivers was a comparatively deluxe LP made for Gramavision, a label that did a lot for creative music in this era. The liner notes are notable, for each composer goes into detail about the structure of each piece. “Juneteenth” is about the “holiday,” about joyous swing, about Thelonious Monk…and also about the fervent embrace of advanced European idioms by African-Americans. The notated part of “Juneteenth” is truly difficult and abstract.

James Newton, Anthony Davis, and Abdul Wadud were all pioneers. These days orchestras are looking for diversity, but it was a very different situation in 1982. When I interviewed Newton, he offered a telling comment concerning the New York Philharmonic.

I LOVE ABDUL WADUD! Let me now tell you something. Let’s go back to the blues. Wadud knew how to play the blues and had a deep feeling for it. It’s like if you could imagine Robert Johnson playing the cello, there it is, you know?

Then let’s go to another extreme: I remember when we did Anthony Davis’s piece, Still Waters, written for the trio, with the New York Philharmonic.

(We were all impacted by Toru Takemitsu’s music. Takemitsu wrote a piece for Tashi and then created a second version with orchestra entitled Quatrain. That was similar to what Anthony did: Still Waters could be for a trio or work with trio plus symphony orchestra.)

We were on the stage at Alice Tully Hall. We walked on the stage, and the orchestra was like, “OK, who are these guys?” Almost always, when you work with orchestras, you get to the point where you have to prove something to them. There are very few times when you get the support you need right away. You need to prove to them that you know what’s going on, and you know how to navigate in that environment in a way that can make the music can happen. OK, we started rehearsing a lot of written passages with them, and after about 15 minutes into the rehearsal, the principal cellist says, “Mr. Wadud, could you please tell me the fingering that you’re using for that particular phrase?” Then, it was over. We had won! The orchestra could not believe the three of us. They were like, “Who are these cats? How come we don’t know about them?”

If I had to pick five musicians that I have worked with in my life where I cherished the experience of working with them, Wadud would easily be on that list. He’d probably be in the top three. He could work with so many different composers; he is a composer himself, he is a complete musician and so stylistically diverse and can articulate so many different styles of music with full authority. And just a cat that is so much fun to be around. I read something recently where he said, “Anthony Davis and James, those are my boys!” Well, he’s our boy! I could not imagine the cello doing what it was able to do in Abdul’s hands and hear something else. In that trio we would push each other, and some of the stuff that we demanded the other to play was close to the edge of impossibility. The improvisation impacted the composition, and there was a fluidity. There was almost exponential development with that Trio. I still have in my mind a concert we did in Basel in the early 80s. It was one of those nights where the music was almost perfect. I can’t think of any other experience where I felt that was the case. There was always this long list of things that I think each of us felt we could have done a lot better, but these cats and what we had together was special. And, I think the strongest component in that equation was Abdul Wadud. I really do.

“Still Waters” (Davis) In the quote above, Newton name-checks Takemitsu, and the rhapsodic opening of Davis’s substantial work (the longest on the LP) would pair comfortably with a modernist non-improvising composer of Takemitsu’s stature. As the piece proceeds, the solos, duos, and trios are improvised, yet the aesthetic remains unified with the composed opening. The idea of a true blend of composition and improvisation has been in the air for some time, but the platonic ideal is rarely realized: “Still Waters” is as good an example as I know. A planned (but I believe improvised) sequence of trills/tremolos sets up the graceful return of the opening ideas. The title comes from the 23rd Psalm.

“After You Said Yes” (Newton) The roadmap of the romance is explained in the notes. After an extended intro, a cello solo, and some collective yearning, a chord progression in Ellington tempo finally arrives, changing and charging the atmosphere. Davis takes a jazz solo. What a good blindfold test: who’s this excellent pianist? Besides Duke, the theme may recall a hint of Mingus counterpoint as well.

“Tawaafa” (Wadud) Wadud’s compositional contribution is strikingly charismatic. The flautist and the cellist are at their most unrestrained and virtuosic, while the pianist holds it down in the middle with vamps, drones, and extended techniques. Really quite a unique band, there’s nothing else that sounds like this. According the notes, the piece is in three sections, and the complete title of the work is tripartite: “Tawaafa/Circumambulation/Communion.” The final “holy” theme is flute in unison with plucked piano over dry cello strums, an extraordinary texture.

Both Newton and Davis are currently active and producing some of their best work. However, I’ve Known Rivers remains one of the best documents of their early years.

Bonus track: Eric Dolphy might be considered one of the patron saints on this page, a direct inspiration for Hemphill’s alto and Newton’s flute. Dolphy also made one of the most significant earlier albums to feature cello, Out There from 1960 with Ron Carter on cello (plus George Duvivier on bass and Roy Haynes on drums). Composer Hale Smith was a friend to Dolphy and a mentor to Newton. A nexus of sorts is the simply glorious melody and performance of “Feathers,” written by Smith, and featuring Carter strumming chords, just like the future Wadud.