(This post was written for Charlie Haden and Ruth Cameron.)

Even though Hampton Hawes had a strong and urgent touch, there was always air around his lines. He seemed to breathe his bluesy bebop into the piano. Along with many others, Hawes took Bud Powell and Charlie Parker and blended it with the pastel colors found in California, although Hawes’s unpretentious virtuosity and perfect jazz beat stood out among his West Coast brethren.

When Bird Song came out posthumously in the late 1990s, it was described as a newly-discovered 1956 trio date with Paul Chambers and Lawrence Marable. That was not correct, as there were only four short tracks with that personnel: “Blue ‘n’ Boogie,” “What’s New,” “Blues for Jacque,” and “I’ll Remember April.” The rest of the album is actually Hawes’s regular first trio with Red Mitchell and Chuck Thompson.

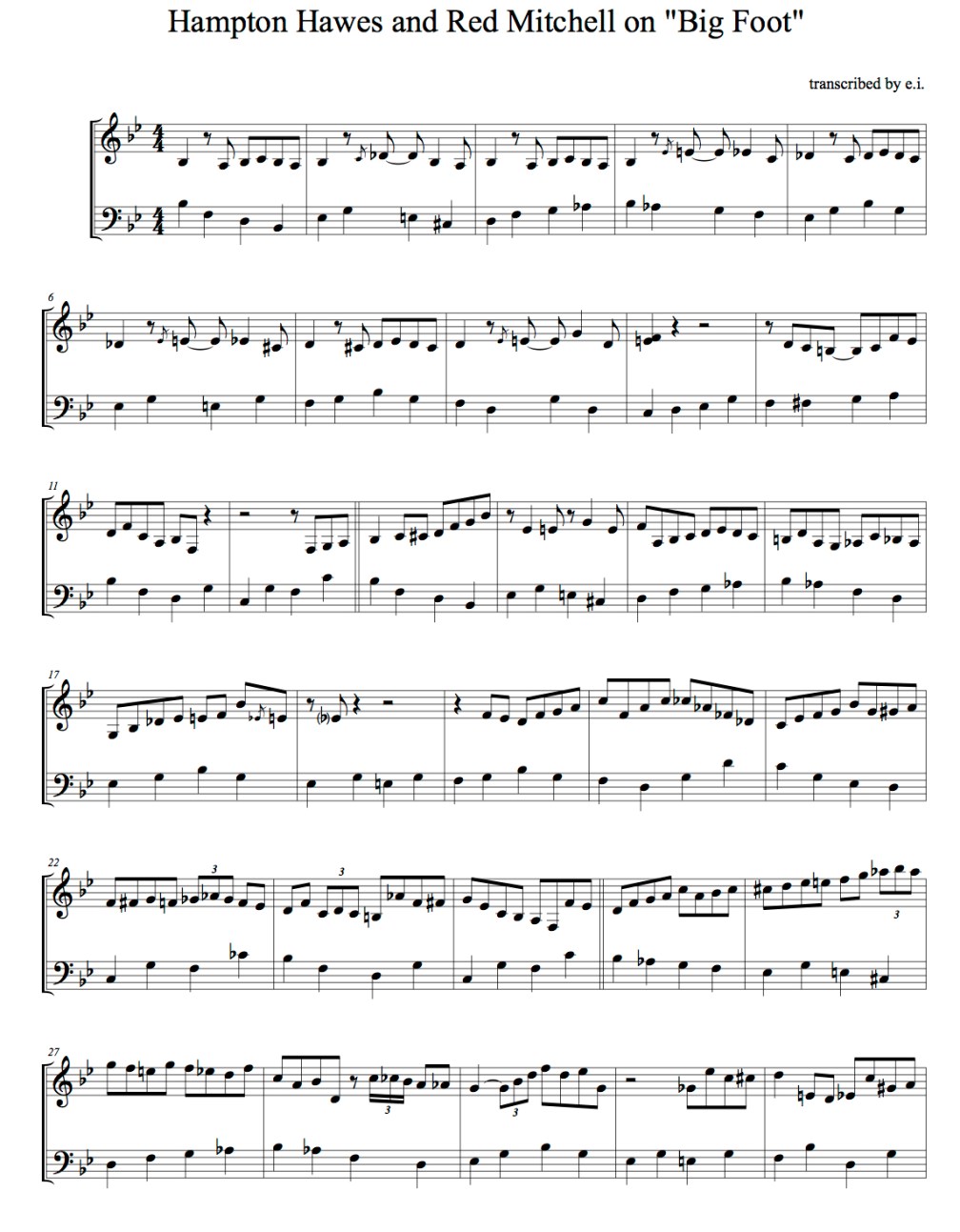

The opening track, “Big Foot” from 1955, showcases Hawes and Mitchell on the uptempo bop blues. Chuck Thompson usually played great with the trio but on “Big Foot” he’s kind of left in the dust by the soaring piano and bass.

From the four tracks with Chambers and Marable, the mid-tempo “Blues for Jacque” gives the best sense of what this one-off trio was capable of.

PC’s lines are really mysterious. Looking at the above line by itself, it’s hard to tell that it’s a blues in F, since the diatonic scales groovily going up and down are almost ignorant of the changes. The music becomes a real ensemble statement with significant bass counterpoint. Marable’s ride cymbal is wonderful, too.

There’s no Bud Powell trio where there’s as much room for the kind of space Mitchell and Chambers have above on these two tracks. Throughout the Hawes discography, you can hear the bass, and you can also hear that Hawes himself is listening to the bass.

More than most pianists of his era, Hawes was intrigued by the way the music opened up in the Sixties. He incorporated the harmony of Bill Evans and McCoy Tyner in a personal way, and in the studio he elicited unusually interactive performances by Monk Montgomery, Steve Ellington, Chuck Israels, Donald Bailey, and others. (David Fink transcribed Hawes and Israels together on “Fly Me to the Moon.”)

The best place to hear Hampton Hawes being influenced by the bass are the duos with Charlie Haden. Haden grew up on the Hawes records with Red Mitchell, eventually got Larance Marable to join him for Quartet West, and was deeply influenced by the diatonic lines of Paul Chambers.

Haden played quite a bit with Hawes in the late Fifties and early Sixties, especially when they were in jail together. They finally met for a recorded conversation in 1976 shortly before Hawes passed away in 1977. The full-length LP As Long As There’s Music shows Hawes reaching not just for dialogue but for total freedom. It’s a very moving document. I can’t imagine another bebop pianist being this vulnerable.

My favorite Hawes-Haden track, though, is on Charlie’s album The Golden Number. This essential record consists of three free-form duos with Ornette Coleman, Don Cherry, and Archie Shepp, plus a blues with Hawes that is quite also “free.”

Charlie’s bass line here was the very first thing I ever tried to transcribe as a kid. It is so abstract within the blues… where is the form in the second chorus?.. sounds great though!

Hawes is with Haden every second, reacting to those outer-space notes with faultless choices and never with too much left hand. There’s even something Ornette-ish about a few of Hawes’s phrases, and the last “heraldic” stuff is pure Don Cherry. No way Hamp would have gotten there without Charlie’s prodding! Haden reacts to Hawes, as well: Dig the way the bass sits on nothing but two bars of “F” under the most gospel-ish piano moment.

—

Some say that Hawes isn’t as good later as he was earlier. It’s true that he slowed down a bit compared to the wonderful run of sparkling Fifties Contemporary albums, which may ultimately be his greatest contribution to the discography overall.

(Vinyl maven Anna Wayland’s HH collection)

But in the Sixties and Seventies Hawes has another kind of wisdom and humility.

Charlie Haden is an obviously alchemical musician, instantly affecting everyone around him. It’s less obvious, but Hawes had something of that alchemical magic as well. He certainly got something special out of Ray Brown and Shelly Manne. Brown and Manne always play great but there can be something a little workmanlike about their attitude. Not with Hawes! On the final trio disc At the Piano all three musicians play together in a kind of reverie.

There’s also a jam session video with Bob Cooper. During the extraordinary piano solo on the opening blues, Brown and Manne dig inside themselves, looking for something a little deeper to keep up with the beat, freedom of phrasing, and natural soulfulness of Hampton Hawes.

—

(Charlie and Reid Anderson duetting on Haden’s glorious basses after the recent Royce Hall gig. Reid has said many times that Charlie Haden is the reason he plays the bass.)

—

For Charlie Haden:

1) Liberation Chorus (memorial thoughts from Charlie’s extended family of musicians)

2) Interview with Charlie Haden (2007)

3) This is Our Mystic (Haden with Ornette) (2010)

4) Hampton Hawes and the Low Blues (2013)

5) Silence (Personal history and anthology of other bits about Charlie on DTM)