Bud Powell Anthology

2) High Bebop

3) The Stuff That Dreams are Made Of

—

At the end of the day, no one could play more bebop than Bud Powell. All that is required to enjoy Powell’s European discography from 1959 on is committed listening.

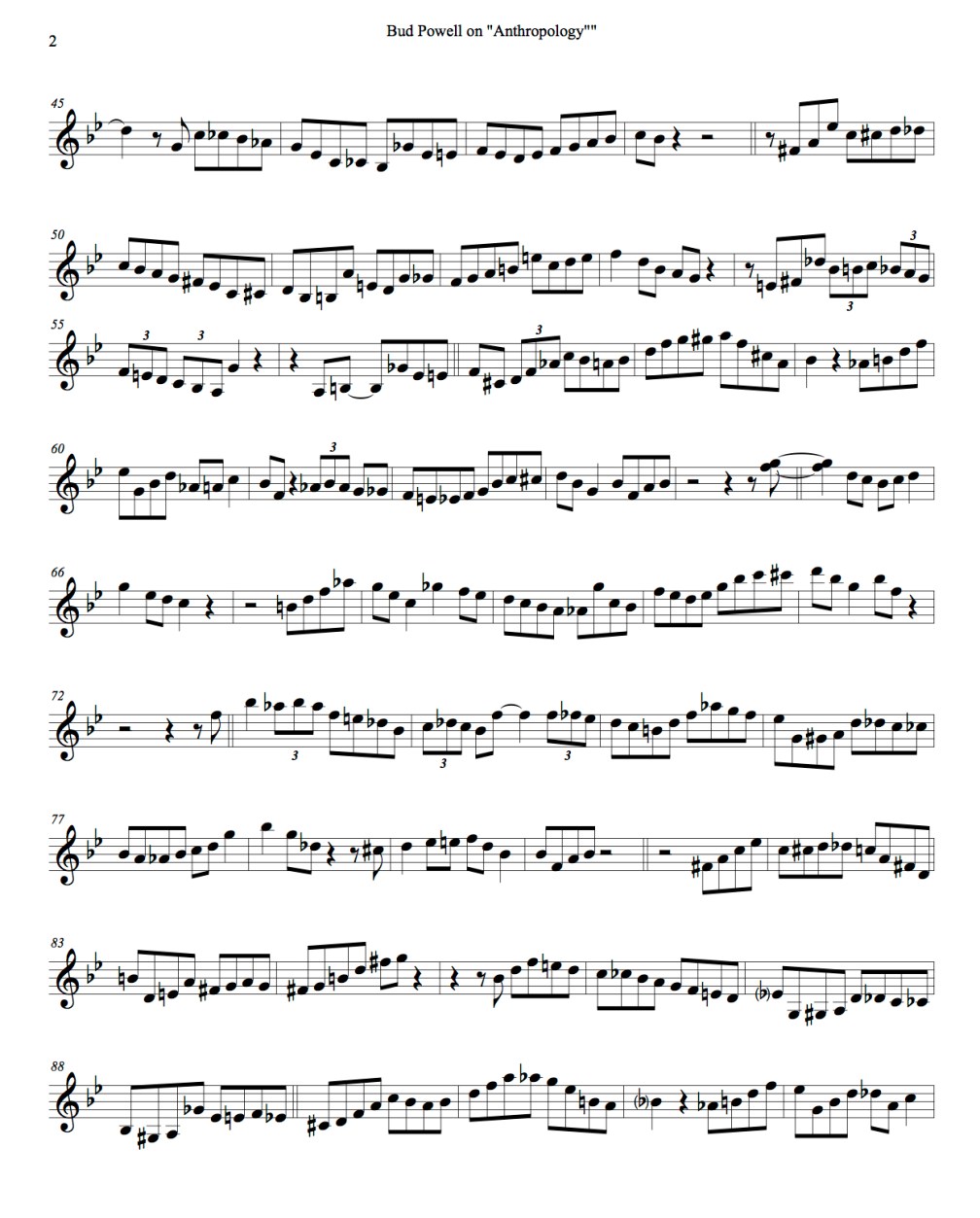

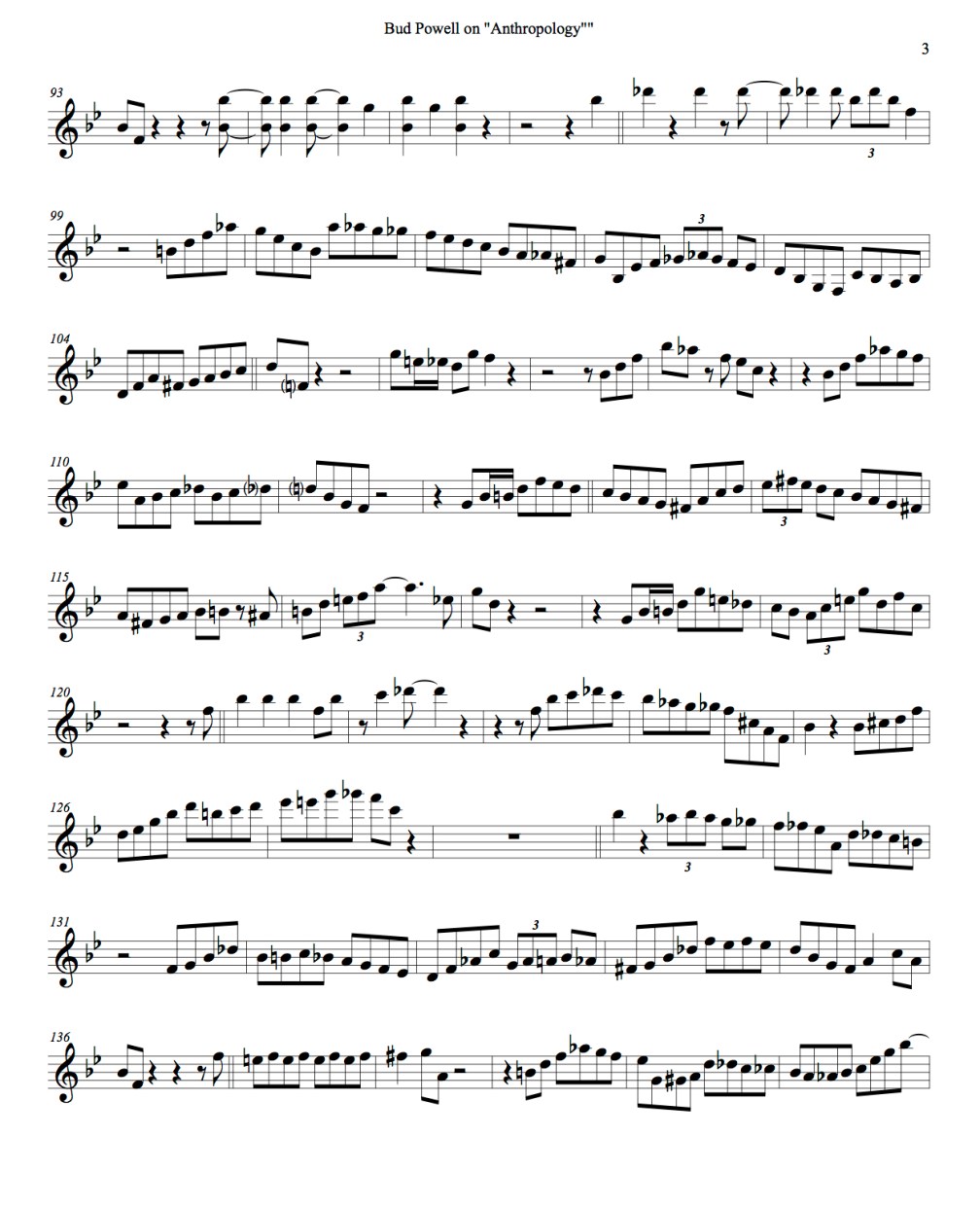

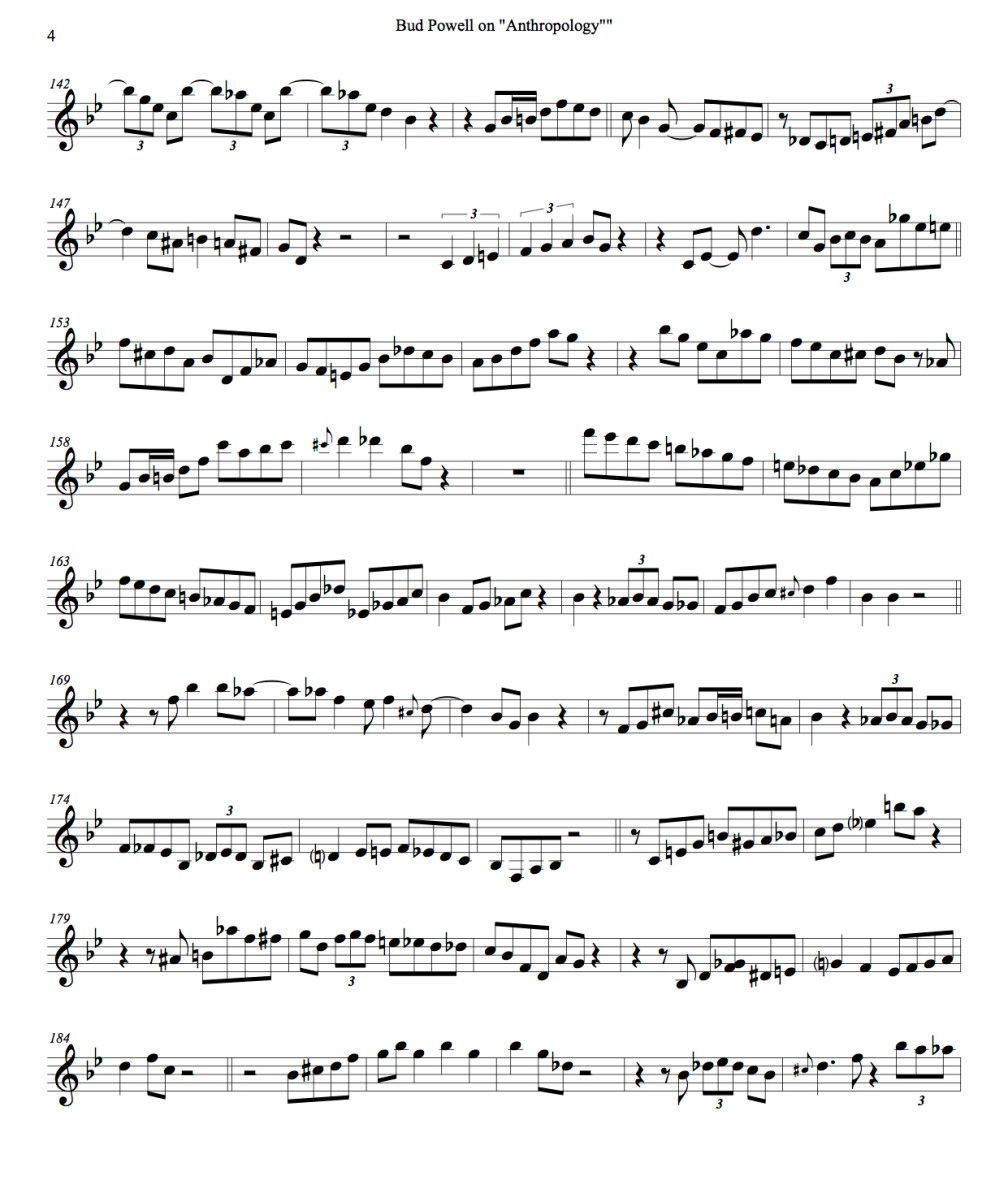

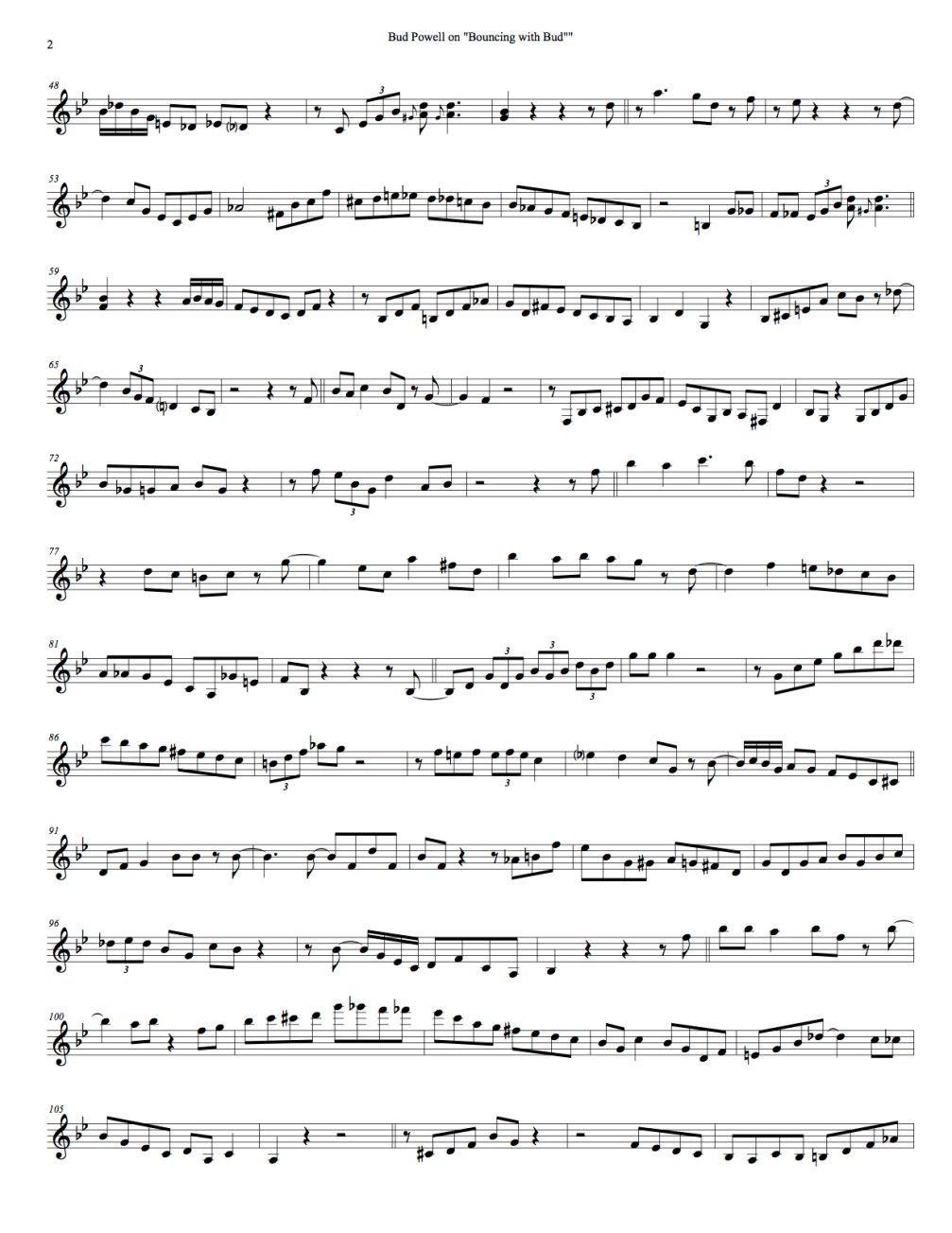

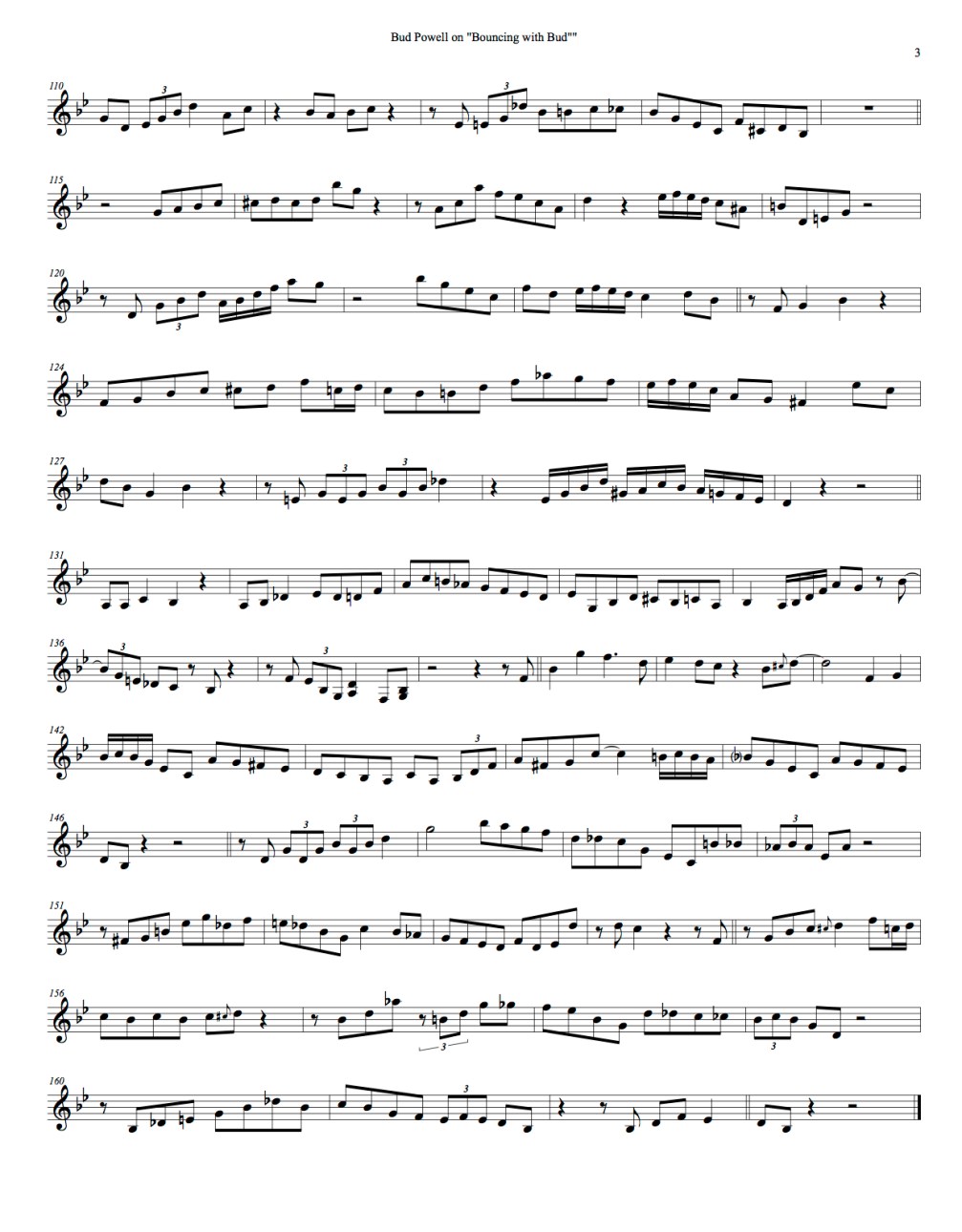

Try the outstanding version of “Anthropology” on the Bud Powell in Europe DVD, also on YouTube. Bud plays mid-tempo rhythm changes as well as it can be done. Thanks to Collin van Ryn for starting this transcription and inspiring me to finish it up. It’s the longest solo in these pages. The scroll simply unrolls.

Not everything Powell recorded during this era is at this level, but the feel is always authentic. He swings so hard, all the time. Hearing him with European musicians can highlight that aspect of his artistry. He powers through with ease and excellence no matter who’s playing bass and drums.

(Not to say that these two on “Anthropology” aren’t very good. Jorn Elniff is swinging, and the amazing Niels-Henning Orsted Pedersen is only 15 or 16 at the time.)

All the Powell performances on Bud Powell in Europe are important. “Anthropology” and a very deep “Blues in the Closet” are at the highest mark, while “Crossing the Channel” and “John’s Abbey” are nearly as great. It’s also sensational to get a look at Kenny Clarke playing the drums for a few tracks.

Powell’s deep connection to his music is even more obvious on video. His hands produce a maximum of sound and dynamic fluctuation with a minimum of effort. Sometimes he was called “hammer fingers,” but actually the fingers are just the final refinement. Like most healthy classical virtuosos, Powell plays the piano with his whole body.

Between phrases Bud hovers, almost relaxed, ready for the next melody to burst forth. In conversation it is important to listen to the end of the previous sentence before beginning the next. Bud always is listening to the start and stops of his line. He never looks at the keys. The affect is something like an endless fountain of perfect bebop.

—

A sample of Bud’s European records:

1959, sitting in on “Bouncing with Bud” and “Dance of the Infidels” with Art Blakey, Lee Morgan, Wayne Shorter, Barney Wilen and Jymie Merritt. Bud sounds good although he might play a few too many choruses. Fascinating to hear Shorter and Powell together. There’s quite a lot about this night in the Shorter biography Footprints. The classic Shorter song “This is For Albert” is dedicated to Powell. (In our interview, Shorter explains that “Albert” was a mishearing of something Blakey said.)

Blakey and Powell didn’t record enough together, really. He’s quite noticeable on the Verve box when he shows up for a few tunes. It’s too bad he picks up brushes for both piano solos, for Bud could have withstood the heat.

Barney Wilen doesn’t have much of an American reputation but he had a secure command of the language and Bud worked with him quite a bit. Here he seems more comfortable on “Bouncing with Bud” than the blues. It certainly takes guts to play alongside burning Lee Morgan and Wayne Shorter. Jymie Merritt is part of that delicious, unrepentant Philadelphia bass committee along with players like Jimmy Garrison. Morgan and Merritt brought some serious Philly to Paris that night.

1960, two tracks duo with Johnny Griffin. Bud swings hard with no rhythm section, Griffin is on fire.

March 12, 1960, two trio tracks with Pierre Michelot and Kenny Clarke. Wonderful succinct versions of “Now’s the Time” and “Confirmation.” Bird lives, Bud lives.

1960, Essen Jazz Festival trio and quartet with Coleman Hawkins, Oscar Pettiford, and Kenny Clarke. Pettiford is the nominal leader on the trio selections and plays great throughout. Sadly it is one of Pettiford’s last sessions. Bud is playing well, though he may be too aggressive for the saxophonist: Hawkins interrupts Bud’s solos on all three swingers. It’s not Hawkins’s best gig of this era.

1960, sitting in with Mingus and one of the greatest Mingus bands at Antibes on “I’ll Remember April.” This was one of my first exposures to Powell, so I know it isn’t a very good introduction for a newbie. Now it is easy for me to appreciate Bud’s authenticity, but in the end still conclude that the non-Powell tunes on this mind-melting album are better. As when he sat in with Blakey, Bud plays a little too long on “April.” Perhaps Powell is trying to prove he is top dog when meeting Blakey, Hawkins, or Mingus on a big European stage.

1961, two sessions produced by Cannonball Adderley, one trio with Pierre Michelot and Kenny Clarke mostly of Monk, the other quartet/quintet with Don Byas and Idrees Sulieman. Michelot is great at holding it down, but he and Klook clearly can’t hear each other too well on the fast tunes with Byas.

Don Byas is one of the greats, but this quintet is neither Byas’s nor Powell’s finest hour. Powell’s inability to play a sensible part on the melody of Duke Pearson’s “Jeannine” shows his lack of curiosity about new music. The best moments are when Sulieman appears like a little bop angel who plays no clichés. The album’s highlight, “Good Bait,” is at that relaxed medium tempo that suited the Sixties Bud best.

That medium tempo helps out a superb piano solo on “There Will Never be Another You” from the next day’s trio session. The Monk covers are a mixed bag.

Lausanne, 1962. The first full album of many casual nightclub appearances of Bud with local rhythm sections. It’s great! Bud shines while playing God with the natives. He’s so swinging and authentic and never has to play too fast. (Indeed, “Woody ‘N You” has never been played so slowly, but it is still beautiful.) Long-time Powell advocate Chick Corea put this out on his own Stretch label.

Geneva, 1962. More of the same with another anonymous band. Equally great. The editing job is a little confusing, they should have just put out what they had without trying to fix it.

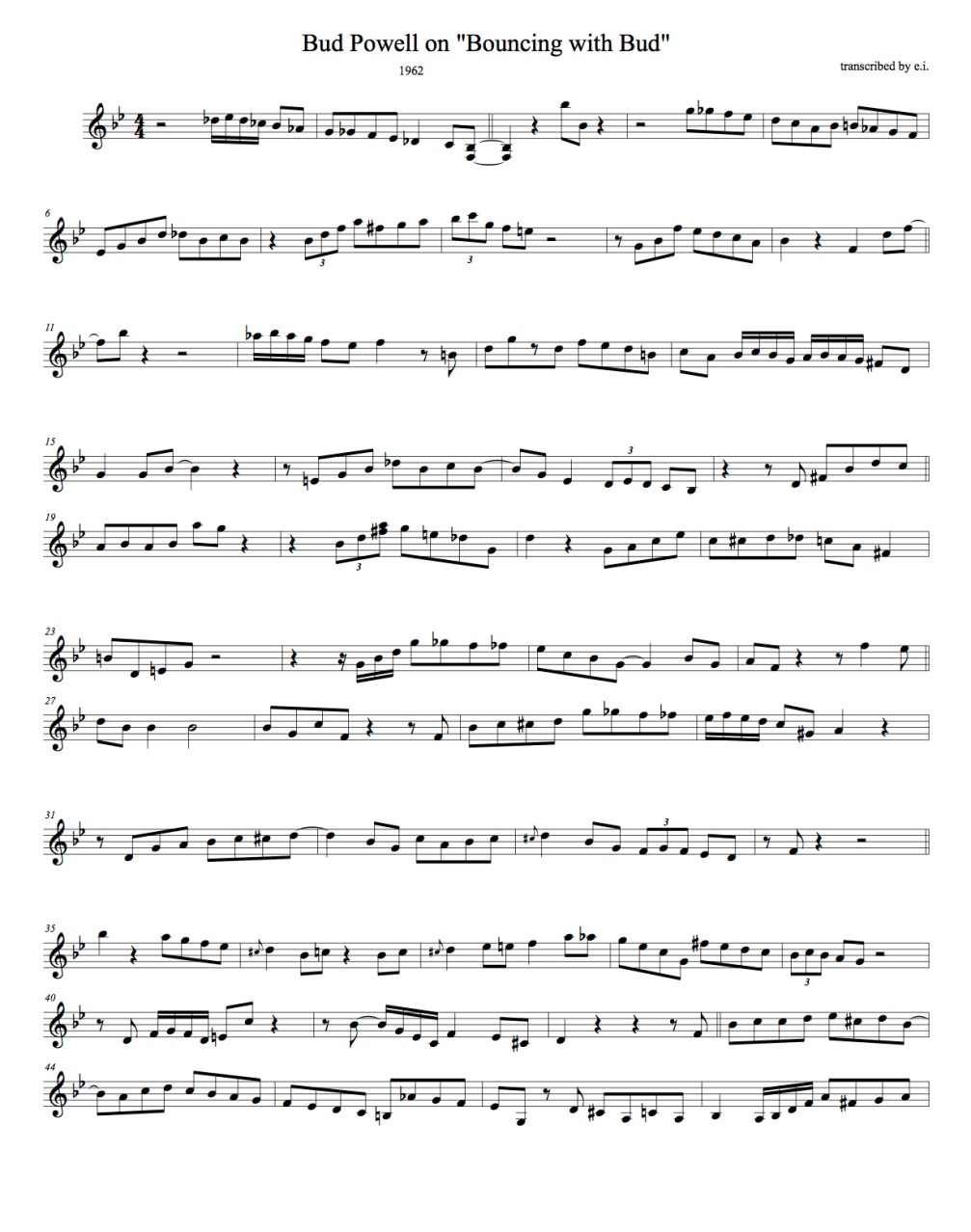

1962, Bouncing with Bud with N.H.O.P. and William Schiopffe. A powerful album that should be much better known. The repertoire choices are terrific. It’s especially interesting to hear Powell’s first trio recording of the title track.

On the melody of “52nd Street Theme,” the bitonal answers and diminished cascades still conjure the furious sidewalk life and car horns of Manhattan. He’s slowed down a bit since 1948 but Bud’s still got it.

1963. Dexter Gordon’s Our Man in Paris belongs in any serious jazz collection. Dexter is divine and the repertoire works for Bud.

Apparently Bud substituted for Kenny Drew at the last minute. Drew was one of several groovy pianists who made prime Blue Note albums with Gordon in those years. It’s intense and refreshing to hear Bud in place of his children Kenny Drew, Sonny Clark, Horace Parlan, or Barry Harris—like encountering Lee Marvin when you expected Sean Penn.

Kenny Clarke is feeling his oats! He must have heard what Elvin Jones and other contemporary drummers were doing. Pierre Michelot is excellent, too. “Stairway to the Stars” even has a great Powell solo on a ballad.

The bonus track is a trio “Like Someone In Love” without Dexter. The rubato intro is fairly cacophonous before the band confidently rolls in and saves the take. The piano solo has phrases that come out of every corner: classic discontinuous continuity.

1961-1964. Eternity and Strictly Confidential. By this point Powell was firmly enmeshed with Francis Paudras, and these two discs are apparently just a small portion of Paudras’s home recordings. As an unreliable Boswell sworn to both protect and interfere with his hero’s posthumous reputation, Paudras ranks somewhere between Charles Kinbote and Robert Craft. The memoir Dance of the Infidels: A Portrait of Bud Powell can not be taken at face value.

Paudras could play piano a little bit and recorded himself thwacking brushes along with solo Powell at his Paris apartment. Unfortunately, Paudras’s rhythm isn’t very good. Unfazed, Bud places his nonchalant yet propulsive beat against Paudras’s amateurism in a professional and non-combative way.

At one point Paudras curated ten volumes of Powell tapes on Mythic Sound, later briefly reissued on CD. They are currently very hard to find. On Vol. 10, Award at Birdland from fall 1964, it’s enjoyable to hear Powell with a tough young New York rhythm section again. John Ore and J.C. Moses can’t influence the music too much, of course, but they sound really good all the same. The highlight is “Star Eyes,” which has a single chorus of superb surreal piano improvisation, concluding with 8 bars of wild, perfectly executed block chords.

—

When Powell died in 1966 he left more questions than answers about his turbulent life. The attention paid to those problems dragged his career down when he was active and still haunt his legacy today.

Bill Coss wrote in the liner notes to Jazz at Massey Hall on Mingus’s Debut label: “Bud Powell, driven mad by beauty or a policeman’s club, has influenced whole scores of pianists. He has no influence over himself. Only the final tragedy is missing; he is still alive.” Can you imagine picking up a record jacket and reading that about yourself?

Who was Charles Mingus to cast the first stone, anyway? When Roy Haynes was interviewed by Anthony Brown for the Smithsonian, Haynes talked about the trio on Inner Fires: “He [Mingus] was going through different things backstage that ended up seeming like he was the one that was just let out of the hospital and that Bud was the cool one.”

Mingus, Bud, Monk, Bird, Miles, Dizzy, Max: this is not a roll call of reasonable men who worked day jobs. These men had a different kind of gig.

Maybe Bud was crazy. However, his mental instability is not the story. The real story is his music.

—

Further reading

While I was originally working on “Bud Powell Anthology,” the book I most wanted to read was Peter Pullman’s biography of Powell. Pullman also wrote extensive notes for The Complete Bud Powell on Verve. The book wasn’t quite out yet, but Pullman graciously contributed the following note when I originally posted in 2012:

HOW I CAME TO WRITE WAIL: THE LIFE OF BUD POWELL

I was working in Verve Records’ reissue department when, in 1994, the opportunity arose for the label to assemble all of its Bud Powell recordings (including all alternative and breakdown takes), for a CD box-set presentation. Michael Lang, who headed the department, was receptive to my offer, to interview musicians and help to put together photos and other graphics for a lengthy, accompanying booklet to the five CDs. He insisted that the booklet have a biographical essay, too, and that I write it.

The set was nominated for a Grammy, in the Best Liner Notes category. I went to the awards ceremony, where I met a number of musicians, including Horace Silver, who’d written an essay for the set. (The Powell lost in its category to a Louis Armstrong-reissue project.)

I also met, at the ceremony, Celia Powell, Bud’s daughter, who warned me about trying to get at the truth about her father. She said that his life story had many question marks, and that if I were to try to answer them I would follow many false leads and meet with a lot of dead ends.

That challenge I sought to undertake, from about 1996: to see if I could get past those dead ends. The first thing to do was to get informed about Powell’s beginnings in Harlem. Celia had advised me to set his early years against the backdrop of the Harlem renaissance, as he was raised in an environment in which lived and worked not only so many great musicians and composers but, as well, painters, poets, and others who aspired to greatness. I undertook learning an informal history of Sugar Hill, the Harlem neighborhood that Powell spent most of his upbringing in. I visited the grounds of the church and schools that he attended, and got access to their transcripts. I educated myself about the many local venues in which musicians hung out in that era — the speakeasies and after-hours places as well as the once-established clubs and ballrooms. I even read fiction (e.g., Claude McKay and Rudolf Fisher) of the era, to get a picture of what, for instance, rent parties were like.

I widened my inquiry, in my desire to understand Powell’s beginnings, to those Harlemites who’d known him even casually, as a kid in the neighborhood. (Remember, Bud Powell came from a small family, and one of his two brothers had died in 1956. His mother died in 1961 and, by the time that I began my quest to learn about his life, his father was dead. I learned as well that his other brother, who had decades earlier distanced himself from everyone connected to the Bud Powell story, died in 1995.)

At the same time, I began my investigation of the mental-health world of the Forties and Fifties, as I knew (inchoately; in some ways, inaccurately) that Powell had been incarcerated in various places for long stretches of time. I interviewed psychiatric nurses as well as MDs, and I began to build my case for access to the files that certain institutions had kept on him (I’d assumed, rightly as it turned out, that these files hadn’t been destroyed). I successfully petitioned two hospitals to see what they had on him and, eventually, won a case in State Supreme Court. This allowed me to read a file on Powell that Office of Mental Health, based in Albany, New York, had kept sealed (hitherto in perpetuity).

* * * *

BUD POWELL came up in an era where his music, and that of his close colleagues, was first and foremost entertainment. (Which he delivered six nights a week, four or five times a night, in the clubs and, sometimes, for many hours afterward in informal settings.) That might sound hackneyed to say but, today, with all of the masters theses that are being produced, and the other art theory-laden expostulations that are making it to print and into video documentaries, it needs to be reiterated.

So I never stopped looking for musicians to talk to, from all parts of his career, especially as most of them were getting on, so to speak, in years. I interviewed many who’d played or recorded with him, those whom I’d not gotten to for the box set. I talked with some who had known Powell only from having visited Birdland once or twice to hear him. Others whom I reached had only heard him in an informal performance, at someone’s apartment.

The musicians whom I spoke to constantly surprised me by how diverse their reactions to particular recorded pieces of his were — and how different their reactions were to seeing him live — while all agree that his talent was unparalleled in his time. Fans’ reactions, too, I quickly learned, were so variable; yet, they have been often simplified in print, where they appear at all, to a cliché (e.g., “Seeing Powell play was an unforgettable experience”).

Powell, in the clubs, was a phenomenon that anyone who cared at all for jazz had to witness. (Maybe, in his time, fans had more visceral responses only to club performances of Billie Holiday and Charlie Parker.) Part of this, of course, was the emotional content of Powell’s playing. That and, as well — what is unfortunate — the knowledge that fans brought to the clubs, of what they’d heard about Powell’s offstage dissipations and consequent cruel treatment by the police, courts, and hospitals.

So the biggest part of my narrative is Powell’s public life in his prime years, as they played out in the nightclubs. I look at him repeatedly from the fans’ as well as his sidemen’s perspectives, capturing their reactions. None watched him casually; all hung on every note that he struck. The point in dwelling on his nightclub persona: It was where he was most alive; in some periods, where he spent the majority of his hours awake.

In pursuing the whole story of Powell’s life I talked, as well, to those who had worked in the clubs that he played in and those who had produced his record dates (including one, Jack Hooke, whom no one had asked about the date that was done for Roost; the one with “Indiana” and “Bud’s Bubble”). And I got to know the key critics, such as Ira Gitler, who had seen Powell play countless times. Ira was terrifically helpful. (Thanks here, as well, to all at Institute of Jazz Studies, especially the nonpareil of historians, Dan Morgenstern; to Brian Priestley, another distinguished historian and critic, and a dear friend; and to Michael Cuscuna of Blue Note and Mosaic, who has long encouraged me.)

This awakening, of the need to get as diverse a survey of fans’ as well as musicians’ and critics’ responses to Powell, propelled me to start making trips to Europe. People there were even more eager to share their insights — they included, of course, the pianists who’d been inspired by him — and to reveal how much Powell the human being had touched their lives, beyond the notes that they’d heard him play. I came to understand that from the time that he’d attained celebrity status, Powell wasn’t very visible in New York City (when he wasn’t playing). He was, though, much more a public personality in Europe — particularly once he’d moved there, in 1959. (Although the decision to move abroad was not an expression of his disgust with life in New York City but so that he could get hired; a Paris club offered him a job that, some months later, became a steady one and wound up being the longest continuous employment of his career.)

By 1999 I started writing the narrative of Powell’s life but, I realized, there was more to learn about the Europe years. I kept going abroad, having already established a relationship with Powell’s greatest fan, Francis Paudras (who had long since been a legend himself by the time that he invited me to stay at his country estate, in 1997). He gave me access at that time to his substantial Powell archive, and I got to learn much from our long, long evenings spent in conversation. He then died; in 1999, however, I visited the archive again, with the cooperation of his attorney.

I remain ambivalent about Paudras, as from the start I’d felt driven to befriend many other French, as well as Scandinavian and Italian, fans and friends of Powell’s — these relationships soon becoming a corrective to Paudras’s version of the Bud Powell story. I even moved to France, in 2002, in part to tie up some loose ends to my interviews and other research but, as well, to finish the writing of the biography. I returned to live in New York City in 2004. It was a struggle, thereafter, to finish the narrative, to make the hard choices about what to believe — Celia Powell’s warning turning out to be too true — and, then, how to tell the proverbial whole truth and nothing but. The final draft was finished in 2009 and, leaving a publisher whose dilatory editor had no desire to issue the work, I chose in 2010 to issue it as an e-book.

For an ongoing discussion of all things Bud Powell, you can visit my blog, at TheLifeofBudPowell.wordpress.com.

At my website, www.BudPowellBio.com (though it is officially titled www.WailTheLifeofBudPowell.com), there is a substantial excerpt from the work. There is, as well, an annotated chronology, for scholars and fans to browse. Also, I have put at it a number of photos of Powell that have never been made public before.

Complete information about ordering the e-book is also provided there.

Peter Pullman

There’s a tremendous amount of new biographical material in Wail. Pullman’s most notable coups are searching out Powell’s early piano teachers and chasing down all the paper documenting the horrible story of Powell’s humiliating treatment in medical institutions.

Soon after Pullman finally released Wail, Guthrie P. Ramsey Jr. published The Amazing Bud Powell: Black Genius, Jazz History, and the Challenge of Bebop. Powell is a logical topic for Black Studies. Indeed, it is a relief to turn to a book that is uncompromising about race after the obfuscating neologisms “afram” and “euram” found in Pullman’s Wail.

The Amazing Bud Powell is obviously excellent but it is also a product of academia. The challenge for Black Studies taking on jazz remains melding college talk with the real world. Ron Carter says to Art Taylor in Notes and Tones: “All of a sudden Black Studies programs have been getting hot. Everybody is a Black music authority. A lot of them are not, as you know.”

Ramsey ‘s favored commentators Amiri Baraka, Henry Louis Gates, Robin D.G. Kelley, and Ingrid Monson are undoubtedly valuable, but their perspective does not supersede those on the ground actually making the music. To his credit, Ramsey does offer some transcriptions and musical analysis.

Pullman, Ramsey, and I all hear Powell very differently, even to the point of stark disagreement about whether certain tracks are prime Bud or not. Steven Beck offered a perceptive review contrasting Wail and The Amazing Bud Powell in Ethnomusicology Review. Those that have enjoyed my work on Powell here on DTM are strongly encouraged to read both Pullman and Ramsey as well. In some way all this recent activity feels like a new day in the understanding of Bud Powell.

There are a few other valuable sources. Bob Blumenthal’s liner notes to the Blue Note and Roost box are fine, but Mark Gardner’s notes for the Mosaic Blue Note box are longer and more detailed.

Gardner’s Mosaic bio is reproduced in Bouncing with Bud: All the Recordings of Bud Powell by Carl Smith. Frustratingly, the music is cataloged by issue instead of by session date, although the photos of Smith’s record collection are certainly fun for any collector.

Paudras’s unsettling Dance of the Infidels seems to have been the primary source for the mediocre The Glass Enclosure: The Life of Bud Powell by Alan Groves and Alyn Shipton. Among other gaffes, Groves and Shipton dismiss the musical value of all of post-1953 Powell.

In 1994 the Village Voice jazz supplement was “The Earl of Harlem: Bud Powell at 70.” Edited by Gary Giddins, this extensive feature includes articles by Giddins, Eugene Holley, Jr., and Guthrie P. Ramsey, Jr., plus Peter Pullman’s interview with Jackie McLean (which is also reproduced in the Verve notes). Best of all, it also includes little interviews by David Jaffe with Tommy Flanagan, Dick Katz, Walter Bishop Jr., Barry Harris, and John Hicks. Hicks concludes his interview and the supplement in fine poetic fashion: “He was a father of the music—one of the people that makes doing this shit worthwhile.”

—

Coda: Other great pianists play Bud Powell

In the Fifties and Sixties not too many other pianists recorded Bud’s compositions. On Wynton Kelly’s first album there is a “Cherokee” that, while not a Powell tune, is obviously a direct tribute. Red Garland tried out a casually swinging version of “So Sorry Please.”

More important is Phineas Newborn’s truly dazzling “Celia,” which remains a benchmark of virtuosity. Indeed, there’s an argument for this track being the greatest Powell tribute of them all.

Later on, in the era of retrenchment and classification, it is interesting to observe how various masters interpreted Powell on record.

Barry Harris is the most devoted keeper of the pure bebop flame. From 1976, a live “Dance of the Infidels” with Sam Jones and Leroy Williams in Tokyo shows how deeply Barry has contemplated Bud’s alternate blues changes. Barry’s piano lines are always melodic and surprising, yet of course always authentic to the style. “Un Poco Loco” from the same disc is one of earlier covers of this exceptionally challenging composition.

Keith Jarrett is the antipode of Barry Harris. Keith admitted he hadn’t even heard Bud by the time he was already in a position of taking his first DownBeat blindfold test. His duo version of “Dance of the Infidels” (2007) with Charlie Haden has a brilliant piano solo but Charlie himself told me that he wished Keith had played the melody correctly.

Speaking of Charlie, “Oblivion” (1989) with Geri Allen and Paul Motian is a rare delight. Geri knows her Bud but plays the language her way. The last blast of her solo is even a “judo chop.”

A completely different approach is taken with Kenny Kirkland’s synthesizer amplification of “Celia” (1991). In this case the reference is not only Celia Powell but Celia Cruz, “La Guarachera de Cuba.” Don Alias is on hand to provide additional salsa. Perhaps it’s not an unqualified success but this track has grown on me over the years.

Another important version of “Celia” is the highlight of Chick Corea’s 1997 album-length tribute to Powell. For my own taste, there can be something a little off-putting about Chick’s appropriation of bebop (I’m aware this is a minority opinion) but it would be churlish to not admit that this casual solo track isn’t great piano playing. (Interestingly, Chick plays it in F, not B-flat, sort of like how Bud himself changed keys down a fourth or third on Bud Plays Bird.)

McCoy Tyner is one of Bud’s most important disciples but his 1991 solo version of “Bouncing with Bud” a bit earthbound. Perhaps he’s reading a chart brought in by a producer. It’s also later McCoy: From the Sixties when McCoy was in his prime, the insanely fast “bebop to the stratosphere” of “The Way You Look Tonight” at a jam session with Eric Dolphy is a breathtaking listen. McCoy ignores Mel Lewis: eventually Mel’s high-hat is turned around compared to the pianist. Not sure who is at fault, but in its way this dislocation is also a kind of a tip of a hat to Bud.

Returning to a more authentic situation, Tommy Flanagan offers four delicious Powell pieces on the 1977 anthology They All Played Bebop. “Dance of the Infidels,” “Strictly Confidential” and “Bouncing With Bud,” are duos with Keter Betts and “I’ll Keep Loving You” is solo. Tommy doesn’t play the full melody of “Bouncing” on the way out, an obvious tribute to the abbreviated 78 that Tommy would have first heard as an eager student of the new music in 1948.

—

Bud Powell Anthology

2) High Bebop