In the Washington Post article “Television on the Coast: Shameless Confessions of a Political Junkie” from August 20, 1976, Ross Thomas explained what made him tick.

I am (I confess it with no shame) a gavel-to-gavel political junkie. I got hooked as a child and some of my earliest memories are a curious amalgam of films from the 1930’s and political rallies held in Memorial Park in Oklahoma City where, on a hot summer Depression evening, my parents would sometimes take me to hear the booming oratorical efforts of the likes of Blind Tom Gore, Alfalfa Bill Murray, and a savvy young comer called Mike Monroney.

All thriller writers are interested in politics, but Thomas’s outsized passion for the mid-century American system gave his books a unique ambience, at once humorously bitter and happily jaded.

Thomas was a late bloomer. John Carmody details a complicated history in “Ross Thomas: His Life is Four Open Books” (The Washington Post, March 23, 1969.)

Ross Thomas is 43. For the past seven years or so in this town he has been considered one of the top two or three pro free-lance writers and public relations experts. He was one of those men government agency chiefs and labor union bosses and politicians (mostly Democrats) called in to write speeches or magazine articles or brochures or to help run some campaign for public or private office.

He was paid $60 a day if he didn’t feel like dickering over it and he could bang out the speeches in an hour and a half, which usually made the man he was working for jealous…

Then about three years ago he suddenly said the hellwithit and sat down and wrote a novel in six weeks. This was while he was working at VISTA headquarters, banging out his stuff on an old Royal, literally sitting at a packing case desk.

The same Post article also describes Thomas’s war experience in the Philippines, his public relations work for the National Farmers Union, and his speech-writing for Hubert Humphrey. In Washington, Thomas served on high-level labor councils before leaving for Denver to start his own PR firm. He helped lead a successful campaign for the Colorado governorship, and another successful congressional campaign for George McGovern in South Dakota.

Thomas’s subsequent political work in Nigeria involved “the world of big business protecting its interests in a new market,” Carmody reported. “Thomas recalls with a certain jaded relish the chartered Royal Dutch Shell helicopters and the dickering over Pepsi Cola plants.” In 1961, Thomas returned to the United States, where he continued his career in labor and PR. He wrote for the Post himself, and was a foreign correspondent in Bonn.

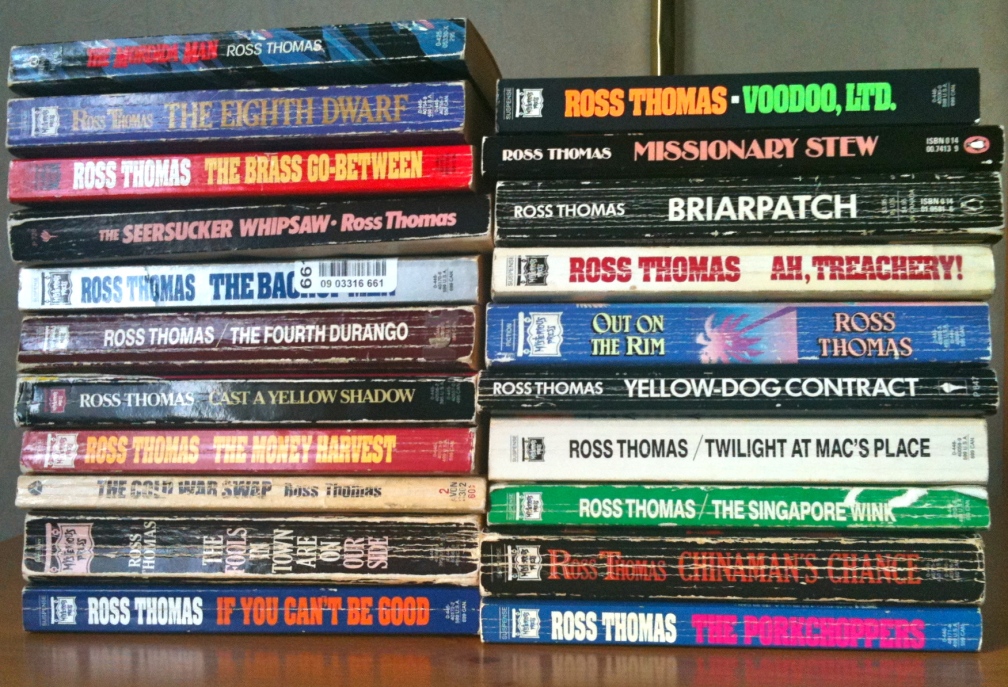

Every part of Thomas’s diverse CV finds its way into one of his novels. There are 25 of them, written between 1966 and 1994.

—

The Cold War Swap (1966) Introduces “Mac” McCorkle and Mike Padillo in West and East Germany. Like Len Deighton (whom he must have read), Thomas put the ironic voice of Raymond Chandler into the spy novel. Thomas wrote in the Post about Chandler’s detective, Philip Marlowe:

One hour and thirty five minutes before we were to land on the beach of an island in the Philippines called Cebu, the first scout handed me something called Farewell, My Lovely, by someone called Raymond Chandler. It was January of 1945, and I was eighteen.

The title sounded as if it could have been thought up by the American equivalent of Agatha Christie, whose works to this day I cannot read. Imagine my surprise, as Dame Agatha might say, when I opened it to discover Philip Marlowe over on that mixed Central Avenue block in east Los Angeles.

Chandler remains fresh thanks to his astonishing ability to write perfect little scenes populated by outrageous characters. The plot of Farewell, My Lovely is hard to follow, but the vivid actions and images are unforgettable: huge Moose Malloy, the insect in detective-lieutenant Nulty’s office, the twit Lindsay Marriott’s pride in a small modern sculpture that Marlowe calls “Two Warts on a Fanny.”

When fashioning a surreal vignette, Thomas could rival Chandler. Forty pages in, The Cold War Swap comes to life when McCorkle visits an old friend. This scene draws on Thomas’s own experiences as a radio journalist in Bonn.

“Come on in and have a drink.” The voice was deep and mellow.

The door opened wide and I went into the apartment of Cook G. Baker, Bonn correspondent for an international radio news service called Global Reports, Inc. Baker was the one and only professed member of Alcoholics Anonymous in Bonn, and he was a back-slider.

“Hello, Cooky. How’s the booze barrier?”

“I just got up. Care to join me in an eye-opener?”

“I think I’ll pass.”

The apartment was furnished in a haphazard manner. A rumpled day bed. A table or two and an enormous wing-back chair that had a telephone built into one arm and a portable typewriter attached to a stand that swung like a gate. It was Cooky’s office.

Around the room were carefully placed bottles of Ballantine’s Scotch. Some were half full, others nearly so. It was Cooky’s theory that when he wanted a drink he should only have to reach out and there it would be.

“Sometimes when I’m on the floor it’s a hell of a long crawl to the kitchen,” he once explained to me.

Cooky was thirty-three years old that year, and according to Fredl he was the most handsome man she had ever seen. He was a couple of inches over six feet, lean as a whipper, with a high forehead, a perfect nose and a wide mouth that seemed continually to be fighting a smile over some private joke. He wore a dark-blue ascot, a pair of gray flannels that must have cost sixty bucks, and black loafers.

“Sit down, Mac. Coffee?”

“That’ll do.”

“Sugar?”

“If you have it.”

He picked up one of the bottles of Scotch and disappeared into the kitchen. A couple of minutes later he handed me my coffee and then went back for his drink: a half-tumbler of Scotch with a milk chaser.

“Breakfast. Cheers.”

“Cheers.”

He took a long gulp of the Scotch and quickly washed it down with the milk.

“I fell off a week ago,” he said.

“You’ll make it.”

He shook his head sadly and smiled. “Maybe.”

“What do you hear from New York?”

“They’re billing more than thirty-seven million a year now and the money is still being banked to me.”

At twenty-six Cooky had been the boy wonder of Madison Avenue public-relations circles, a founder of Baker, Brickhill and Hillsman.

“I got on the flit one night and just couldn’t get off,” he had explained to me one gloomy night. “They wanted to buy out my interest, but in a moment of sobriety I listened to my lawyers and refused to sell. I’ve got a third of the stock. The more lushed I got, the more stubborn I became. Finally I made a deal. I would get out if they would bank my share of the profits for me. My attorneys handled the whole thing. I’m very rich and I’m very drunk and I know I’m never going to write a book.”

Cooky had been in Bonn for three years. Despite Berlitz and a series of private tutors, he could not learn German. “Mental block,” he had said. “I don’t like the goddamn language and I don’t want to learn it.”

His job was to fill one two-minute news spot a day and occasionally do a live show. His sources were the private secretaries of anyone in town who might have a story. In methodical fashion he had seduced those who were young enough and completely charmed those who were over the edge. I had once spent an afternoon with him while he gathered the news. He had sat in the big chair, the private-joke smile fighting to break through. “Wait,” he had said. “In three minutes the phone will ring.”

It had. First there had been the girl from the Presse Dienst. Then it was one who worked as a stringer for the London Daily Express; when her boss had a story, she made sure that Cooky had it, too. The phone had continued to ring. To all Cooky had been charming, grateful, and sincere.

By eight o’clock the calls had ended and Cooky had gone over his notes. Between us we had managed to finish a fifth. Cooky had glanced around and found a fresh bottle conveniently placed by his chair on the floor. He had tossed it to me. “Mix us a couple more, Mac, while I write this crap.”

He had swung the typewriter toward him, inserted a sheet of paper, and talked the story as he typed. “Chancellor Ludwig Erhard said today that…” He had had two minutes that night, and it had taken him five to write it. “You want to go the studio?”

More than mellow, I had agreed. Cooky had stuck a fifth of Scotch into his macintosh and we had made the dash to the Deutsche Rundfunk station. The engineer had been waiting at the door.

“You have ten minutes, Herr Baker. They have already called you from New York.”

“Plenty of time,” Cooky had said, producing a bottle. The engineer had had a drink, I had had a drink, and Cooky had had a drink. I had been getting drunk, but Cooky had seemed as warm and charming as ever. We had gone into the studio and he gotten on the phone to his editor in New York. The editor had started to reel off the AP and UPI stories that had come over the wire from Bonn.

“I’ve got that…got that…got that. Yeah. That, too. And I’ve got one more on the Ambassador…I don’t give a goddamn if AP doesn’t have it; they’ll move it after nine o’clock.”

We had all had another drink. Cooky had put the earphones on and had talked over the live mike to the engineer in New York. “How they hanging, Frank? That’s good. All right; here we go.”

And Cooky had begun to read. His voice had been excellent, a fifth of Scotch apparently having made no effect. There had been no slurs, no flubs. He had glanced at the clock once, slowed his delivery slightly, and finished in exactly two minutes.

We had had another drink and then proceeded to the saloon, where Cooky and I were to meet two secretaries from the Ministry of Defense. “That,” he had said, on the way to Godesberg, “is how I keep going. If it weren’t for that deadline every afternoon and the fact that I don’t have to get up in the morning, I’d be chasing little men. You know, Mac, you should quit drinking. You’ve got all the earmarks of a lush.”

“My name is Mac and I’m an alcoholic,” I had said automatically.

“That’s the first step. The next time I dry up, we’ll have a long talk.”

“I’ll wait.”

Through what he termed his “little pigeons,” Cooky knew Bonn as few others did. He knew the servant problem at the Argentine Embassy as well as he knew that internal power struggle within the Christian Democratic Union. He never forgot anything. He had once said: “Sometimes I think that’s why I drink: to see if I can’t black out. I never have. I remember every God-awful thing that’s done and said.”

The amount of boozing that goes on in The Cold War Swap defies belief. In a superb essay in Mystery Scene, Lawrence Block sheds light on Thomas’s ways of the bottle. The first two times Block and Thomas socialized, Thomas was a teetotaler. The third occasion in 1973 was right out of a Thomas novel, complete with bribe, armed assistant, limo, and liquid lunch.

He came by around eleven-thirty. He rang my doorbell and I opened the door and there was Ross, with his eyes rolling around in his head. “We’ve got nothing to worry about,” he announced. “I just laid twenty bucks on your doorman.”

And just like that I understood why he didn’t drink.

###

The details of the afternoon are a little vague, and I can’t blame that on the years, because they were vague from the jump. Ross was accompanied by a young man he called the Sergeant-Major, for indiscernible reasons, who seemed to be a sort of driver and bodyguard. The Sergeant-Major went off to do something, and Ross had a seat, and I drank everything I could find in an effort to catch up, because I felt entirely too sober for the company. There was nothing on hand but a few cordials I kept for company, half-pint bottles of Kirschwasser and Goldwasser and Triple Sec, the sort of thing of which nobody would want more than a sip or two, but I braced myself and Made Do.

The Sergeant-Major turned up in time to drive us to Lutece in a limo, picking up my friend Debby en route, where he left us to do something else. (He was armed, Ross told us, and got his gun through airport security—such as it was in those innocent days—by wearing it in an ankle holster.)

At Lutece, they seated the three of us at a lovely table upstairs, and a waiter came to take our drink order. Ross said he wanted a triple vodka martini, straight up and extra dry. The waiter asked if he’d prefer an olive or an onion with that. “We’ll eat later,” Ross announced.

And after that, alas, it all gets rather vague. Ross was in the middle of a two- or three-week toot, and I was no match for him. I blotted my copybook, falling asleep with my head in a plate of Chicken Kiev, but not until I’d had one or two bites of it. It was a specialty at Lutece, and rightly so.

In The Cold War Swap, Mac and Padillo should also be falling into their food, considering the way they knock them back. Instead, they are coolly confident while ringing the changes of an entertaining but fairly predictable spy story.

The Cooky vignette is the best thing in the book, but it also points up one of Thomas’s consistent flaws. Sorry for this lone spoiler, but I must make an example at the beginning of the run: Cooky will turn out to be a traitor and Padillo will kill him, wasting a great character for no compelling reason. In the final pages of too many Thomas books, blood is shed among the friends you trust.

Cast a Yellow Shadow (1967) Thomas makes a go of a series, probably inspired by Deighton, Ian Fleming, and Donald Hamilton. McCorkle is the amateur (read: Thomas himself) and Padillo is the pro (read: Matt Helm). The most memorable aspect about the pair is their joint venture: Mac’s Place, a dimly lit, moderately expensive restaurant where you can get solid food and drink, the staff remembers your name, and no one will comment if you bring somebody else’s wife.

For this installment, Thomas has moved the action to Washington, D.C. Karl, the German bartender, explains why:

Some people hang around police stations. Karl hung around Congress. He had been in the States for less than a year but he could recite the names of the one hundred and thirty-five Representatives in alphabetical order. He knew how they voted on every roll call. He knew when and where committees met and whether their sessions were opened or closed. He could tell you the status of any major piece of legislation in either the Senate or the House and make you a ninety or ninety-five per cent accurate prediction on its chance for passage. He read the Congressional Record faithfully and snickered while he did it. He had worked for me before in a saloon I had once owned in Bonn, but the Bundestag had never amused him. He found Congress one long laugh.

Thomas knew this millieu was distinctive. His 1972 Post article “Washington: The Spy Novelist’s Delight” anthologizes nine D.C. vignettes from various books (including Karl the bartender). Thomas concludes:

For a living I write suspense novels, or thrillers, or perhaps as Graham Green describes them, entertainments. They do reasonably well, if not as well as I would like, and their backgrounds, often as not, are laid in Washington, which in my opinion, has more sharpies and sonsofbitches per square foot than any place in Christendom.

After Chandler, Thomas’s other big influence is Dashiell Hammett. Yellow Shadow appropriates the general model of The Maltese Falcon, where there are no real heroes, just a collection of scalawags who never trusted each other to begin with. But in Thomas’s case, the labyrinth of deception and double-cross may undercut the possibility of a logical conclusion. At the end of Yellow Shadow, only Mac and Padillo are left. Considering how many associates have been involved along the way, that’s just silly.

It’s telling that Thomas dismissed Agatha Christie as unreadable. Hammett, a superior plotter than Chandler or Thomas, bragged that one of the clues in The Maltese Falcon was worthy of Christie.

The Seersucker Whipsaw (1967) The first of Thomas’s elegant and dispassionate tales of fixers rounding up the votes by defaming the opposition and paying off the union. Thomas is getting into gear, and Padillo has only a tiny cameo.

Hammett’s Red Harvest and The Glass Key are about dirty municipal politics. The peace officers in Chandler’s Bay City define the corrupt cops motif in genre fiction. However, most classic crime and espionage tales ignore quotidian general elections. It is fun to guess what else Thomas might have read when imagining telling this kind of story. Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men is an obvious candidate, and W.R. Burnett’s Vanity Row (1952) and Donald E. Westlake’s Killy (1964) are great tales of city machines and union elections.

Of course, it was Thomas’s own life experience was his biggest source. The classic political Thomas novels remain a genre unto their own. An apt quote from the Village Voice adorns many of the books: “What Elmore Leonard does for crime in the streets, Ross Thomas does for crime in the suites.”

Seersucker Whipsaw is set in Africa. In its overture, Clinton Shartelle is called back into harness to, “Inject a little American razzamatazz into the campaign.”

“You have the reputation as the best rough-and-tumble campaign manager in the United States. You have six metropolitan mayors, five governors, three U.S. Senators, and nine Congressmen that you can honestly claim credit for. You’ve defeated the sales tax in four states, and got it passed in one. You got an oil severance tax passed in two states and got the resulting revenue earmarked for schools in one of them. In other words, you’re the best that’s available and Padraic Duffy told me to tell you he said that. You’ve to do whatever has to be done to get Chief Akomolo elected.”

Thomas actually ran a campaign for Chief Obafemi Awolowo in Nigeria, so the local details have the ring of truth. Thomas’s article for the Post, “The Great Nigerian Razzamatazz Scheme,” is dated March 23, 1975.

In the article, Thomas gives a few details that sound just like his books.

The proper practice of modern American political techniques, of course, requires the presence of media. In Nigeria there wasn’t any. There was television, but no sets. There was radio, but it was government controlled. There were newspapers, but they were pretty awful and not much read and even less believed. And besides, each of them hewed pretty close to their own particular party line.

So Filthy Fred and I invented our own medium. We borrowed the sky. Up there in the African blue we and a refugee from the RAF wrote “AWO” over and over with an old biplane that he flew down from London.

There’s no hard evidence to prove that the CIA anted up for Chief Obafemi Awolowo’s campaign. But somebody did and it certainly wasn’t MI6. After all, Chief Awolowo was the CIA’s kind of folks. He was left, but not too far left, and he hated the British. If he got elected, then the Americans would become the dominant friendly foreign power in the land of the cocoa bean. They weren’t worried about oil then. They knew that there was oil in Nigeria, but they didn’t know quite how much. If they had known — and here I’m assuming that they are the CIA — they might have spent a little bit more money. Maybe another couple of million.

To create an exciting novel, Thomas has to draw on his imagination, not just the facts. In Seersucker Whipsaw Shartelle does indeed do, “Whatever has to be done to get Chief Akomolo elected,” and it’s far more extreme than skywriting.

The only things holding the novel back are an ostentatious love interest and, in the epilogue, a surprise dive into heroism. It doesn’t matter. This is the first great Ross Thomas.

The Singapore Wink (1969) How to energize the hero? McCorkle and Padillo went on self-serving espionage missions while Shartelle ran an election. In Singapore Wink, the Mafia pressures ex-stuntman Edward Cauthorne to resolve an old mystery. According to Carmody, the Mafia stuff comes from another unpublished book: Thomas was hired to work on the Joseph Valachi memoir. Legal tangles led to his replacement with Peter Maas. Thomas told Carmody that he learned enough about the Mafia for “seven or eight novels,” but this is the only Thomas book that includes Mafia clichés. (There’s a comparatively minimal Mob element in The Money Harvest.)

The Singapore Wink is not all that believable to begin with, and eventually there are too many double-crosses. The best parts of the book center on the upscale Hollywood store Les Voitures Anciennes, where Cauthorne and Richard K.E. Trippet restore old American cars to mint condition. Woody Haut observes that “small-time entrepreneurism invariably appeals to Thomas’s protagonists, only for them to be dragged back into the world of spooks and scams.”

While in Singapore, Cauthorne shuttles money and information to and from the Mafia, the local police, the home police, and assorted other criminals. Thomas became fascinated with the idea of a paid professional working a self-interested middle between the law and the lawbreakers: a go-between.

The Brass Go-Between (1969) (as Oliver Bleeck) Thomas’s pen name, Oliver Bleeck, chronicled Philip St. Ives, the man who both criminals and victims trust to resolve tricky situations.

Has this kind of “go-between” ever really existed? Probably not, but it’s no less likely than a private detective who solves murders or a daredevil spy. Thomas wrote of real-life German lawyer Wolfgang Vogel in “Shcharansky Free At Last” (collected in Spies, Thumbsuckers, Etc.), calling him a “professional go-between.” Fictional examples are easier to find: Sam Spade is arguably a go-between in The Maltese Falcon, and Eric Ambler’s minor thriller A Kind of Anger from 1964 might prefigure the Bleeck series.

At any rate, almost all of Thomas’s future heroes are willing to work the middle.

Thomas didn’t change his voice for the Bleeck series. Lawrence Block remembers, “One day in 1969 I came across a new book called The Brass Go-Between, by one Oliver Bleeck, identified by his publisher as the pseudonym of a well-known writer… I opened the book, read two or three pages, and knew at once just what well-known writer had written these words.”

Indeed, who else could have written this minor vignette?

Albert Shippo and Associates’ office was at East 24th Street on the eighth floor of the George Building, which was as unimpressive as its name. There were two elevators, but only one of them was working under the captaincy of a shabbily dressed old man with a face the color and texture of a worn peach pit and pure white hair that hung down to his shoulders. He jerked the handle when I said, “eight,” and when the door didn’t close, he kicked it with a scuffed cowboy boot. The elevator responded, grudgingly, it seemed, and we creaked upward.

At the second floor, he turned to look at me. “Don’t get any ideas, rube. I ain’t one of them just because of the long hair.”

“I didn’t think you were.”

“Some folks get the wrong idea. I rode with Bill, you know. Madison Square Garden, nineteen-ought-nine.”

“Bill?”

“Bill Cody, you dumb shit. William Frederick Cody. Buffalo Bill.”

“You were in his Wild West Show, huh?”

“Dammed right I was. We all wore our hair long like this from Bill on down. Now folks think I’m one of those Village punks, but I ain’t. I’m part Indian, too. Chickasaw on my mother’s side.”

“You must have some great memories,” I said as the elevator croaked to a stop at the eighth floor.

“They ain’t so hot,” the old man said.

The Brass Go-Between is filled with humor and action set in the ideal Thomas arenas of New York City and Washington D.C. The Procane Chronicle offers stars a memorable thief in the title role and is filled with superb descriptions of NYC bars.

Procane was filmed as St. Ives starring Charles Bronson. Thomas’s article for the Post, “My Thriller: I Lost it at the Movies” (October 10, 1976) is amusing.

After five minutes of watching I realized that nothing of mine was going to be used except the skeleton of the plot. When I had met Charles Bronson on the set, he had told me, “I haven’t read your book.” That’s okay, I said, I didn’t see your last picture.

St. Ives. is the only Thomas novel adapted for film. However, Thomas did have had a hand in the marginally successful screenplay of Hammett and gets sole screenwriter credit the Lawrence Fishburne/Ellen Barkin vehicle Bad Company,. Sadly, Bad Company (which came out just before Thomas died) is entirely forgettable. Anything Thomas wrote is remote and “knowing,” but Bad Company grits its teeth with determination. Big boss Frank Langella wearing waders while fishing in a large pool built inside his office is the only image authentic to Thomas’s own voice.

Back to Bleeck: I admire The Brass Go-Between and The Procane Chronicle, but Protocol for a Kidnapping, The Highbinders, and No Questions Asked are lesser works, probably only for completists. Despite the occasional great Thomas paragraph and some funny characters, they have the feel of being written too quickly for a paycheck.

Around the same time as The Brass Go-Between, Thomas co-authored Warriors for the Poor: The Story of VISTA, Volunteers In Service to America with William H. Crook, a nonfiction account of a still active government agency informally known as “the domestic peace corps.” The prose is quite leaden, so undoubtedly it is more Crook than Thomas. The comment in Carmody is amusing:

…Recently completed a book for a $2000 fee (with William Crook, the former director) on VISTA which has taken a terrible panning from critics. This does not faze Thomas because he knows precisely what kind of book was expected from an old pro called in to do a job.

Some of the chapter titles in Warriors for the Poor are fabulous:

How to Reach Forty Without Selling Out

Dead for All Intents and Purposes

This Used to Be a Real Nice Neighborhood

Baltimore Is a Big, Dead Fish, But My Mother Likes It

The Next Social Worker Will Be Shot

Don’t Mention Block Clubs in Miami Beach

A Master’s Degree in Poverty

If You Can’t Raise $35 Bail, You’re Indigent

“Dead for All Intents and Purposes” is almost interesting as it gives the history of how the first bill to create the National Service Corps (the precursor of VISTA) was not passed in the House and the Senate. This is just the kind of thing Karl the German bartender would know the real story behind! However, none of Thomas’s rapier wit gets to be used on the real people involved. I found it rather a slog, although perhaps it would be fascinating to those who study ’60s politics. At the end of the chapter, a paragraph sounds informed by the master. I italicize two snooze-worthy sentences in the middle, presumably William H. Crook’s work.

The Kennedy Administration had made a valiant but unsuccessful effort to transfer the charisma of the Peace Corps to the National Service Corps which, despite herculean efforts to alter its image, still remained something of an ugly duckling, just a trifle ridiculous perhaps, even a little quaint. Overlooked by Congress was the fact that the corps would be a unique departure in the history of American aid to the disadvantaged. Never before had there been the opportunity to dispatch trained full-time volunteers into the poverty of the nation. [Snooze.] Although the do-gooders were undoubtedly needed, the approach to Congress had smacked too much of Madison Avenue and too little of the grass roots. It had all been just a trifle too glossy, a trifle too slick, a trifle too arrogant for the preponderantly conservative representatives of the people who composed the first session of the 88th Congress.

Ultimately Warriors for the Poor was just another job supplying future material: In The Porkchoppers, Kelly Cubbin spends time in a VISTA-type organization.

The Fools in Town Are on Our Side (1970) An agent provocateur goes in to clean up a corrupt town. Thomas obviously shows a debt to Hammett’s Red Harvest. One question always remains about the older masterpiece: Would all the entrenched criminals really keep the Continental Op around after he starts successfully stirring up trouble? Since Lucifer Dye is a paid criminal himself, with both sides wondering if he’s really working for them, in a way Thomas’s story is a little more believable.

Thomas flexes his authorial muscles in Fools in Town. Even the title, which comes from Mark Twain—“Hain’t we got all the fools in town on our side? And ain’t that a big enough majority in any town?”—shows an attempt to work a bigger sociological canvas. Thomas is entirely successful; Fools is one of his best books.

In one famous passage, Thomas decodes Swankerton, a fictional town somewhere in Texas or Oklahoma. (If the burg is Oklahoma City, it’s more disguised than in the later Briarpatch.)

Swankerton had the outline of a squatty pear; its fat bottom sprawled along the expensive Gulf Coast beach and then tapered reluctantly north into quiet, middle-income residential areas whose forty and fifty-year old elms and weeping willows cooled and shaded streets where parking was still no problem. In the warm evenings the owners of the neat houses came home, changed into bermuda shorts, and stood about, gin and tonic in hand, watching their creepy-crawler sprinklers wet down the thick green lawns and wondering whether it wasn’t the right time to sell and move to the suburbs, now that the place was looking so nice.

Farther up the pear, just below the neck, the neat homes and green lawns made way for ugly frame houses that once may have been bright green or blue or even yellow, but were now mostly a disappointed gray, ugly as old soldiers. The poor whites lived there, the millhands and the rednecks and their big-boned wives and tow-headed kids. The gray houses weren’t really old. Most had been built right after World War II to accommodate the returning warriors and they had been thrown up fast in developments that went by such names as Monterrey Vistas and Vahlmall Gardens and Lakeview Acres. They had been cheaply built and cheaply financed with four percent VA loans and no money down to vets.

But the vets who had lived there right after World War II had long since moved away. The lawns had turned brown and some of the trees had died and the concrete streets with the fancy names were broken. Nearly every block had one or two rusting shrines to despair in the form of a ’49 Ford with a busted block or a ’51 Pontiac with frozen main bearings. Nobody admitted that the shrines even existed because admission implied ownership and it cost fifteen dollars to have them towed away.

The owners and renters here came home after work too, but they didn’t change into anything. Those who worked the day shift just sat around on the shady side of the house in their plastic-webbed lawn chairs that they got at the drugstore for $1.98 each and drank Jax beer and yelled at their kids.

The gray houses with their composition roofs kept on going block after block until they ran against the railroad tracks which split Swankerton neatly in two about halfway up the pear. The tracks, which ran all the way from Washington to Houston, served as the city’s color line. North of the tracks was black. South was white.

When you crossed the tracks leading north you found yourself in another enclave of neat houses and emerald lawns and creepy-crawler sprinklers. It lasted for almost twelve blocks. The owners here were black and after work they came home and stood around, martini in hand, and wondered whether they should buy their wives a Camaro or one of those new Javelins. They were N-town’s affluent, its political leaders, its doctors and dentists, its morticians, schoolteachers, lawyers, skilled workers, restaurant owners, insurance salesmen, policy men, and the Federal civil servants who worked out at the big Air Force depot.

Past these well-tended houses and still father up the neck of the pear spread the rest of N-town, a collection of flimsy, gimcrack houses, often duplexes, whose sides were covered with Permastone or imitation brick and which often as not leaned crazily at each other. And on the edge of the city, just before the suburban sprawl began, was Shacktown, a fully integrated city, composed of packing-crate hovels, abandoned buses, and ancient house trailers that hadn’t been moved in twenty years. In Shacktown teeth were bad and bellies were swollen and eyes were glazed. Those who lived there had given up everything, but the last luxury to go had been the comforting awareness of racial identity. But now that had gone, too, and everyone in Shacktown was almost colorblind.

The stem of the pear was the Strip, a three-mile-long double strand of junkyards, motels, gas stations, nightclubs, roadhouses, and honkytonks. Interspersed among these were the franchised food spots, all glass and godawful colors, that hugged the highway to offer fried chicken and hamburgers which all tasted the same but signaled the weary traveler that a kind of civilization lay just a little way ahead.

The Strip sliced outlying suburbia neatly in two, skirted Shacktown, and when it reached the city limits they called it MacArthur Drive. Desk-top flat and six and eight and even ten lanes wide, it rolled and twisted all the way down from Chicago and St. Louis and Memphis, taking bang-on aim at the Gulf of Mexico. They called it the Strip sometimes but more often just U.S. 97. It was the river that Swankerton had never had, the route of the endless caravan of semis and articulated vans, big as box cars, that growled up hills in low tenth gear and roared down the other side, seventy and eighty miles per hour, black smoke snorting from their diesel stacks and their drivers praying for the goddamned brakes to hold. The teamsters rolled them night and day down the highway that linked the city with the North and the West and they handled more freight in a day than the railroads did in a week. They rolled down from Pittsburgh and Minneapolis and Omaha and Chicago and Detroit and Cleveland, bringing Swankerton what it couldn’t grow and what it couldn’t make itself, which was just about everything except textiles and vice.

Lucifer Dye’s assistant is Homer Necessary, the ex-police chief with one blue and one brown eye. He’s corrupt, mean, and he gets the job done.

Then he turned to the young man in the chair. “You got a name?”

“Frank. Frank Smith. That’s the God’s truth. It’s Smith.”

Necessary returned the blackjack to his hip pocket and slapped Frank Smith across the face. It was a hard, brisk slap. “That’s what you get for telling the truth, Frank. You can just let your imagination work on what you’re going to get when you start lying.”

Not if, I noticed, but when. I lit a cigarette and watched the ex-chief operate. I decided that he must have enjoyed his former line of work.

Thomas almost always wrote about male partnerships. Unusually, it takes nearly all of Fools in Town for Dye and Necessary to bond. It’s too bad Thomas retired them after a single book, but if you run across them somewhere, perhaps you could hire them yourself, if the money was right.

My one mild criticism of Fools is that the main story about Swankerton is plenty; we don’t need the entire Shanghai/Section Two segment as well. Indeed, that whole backstory could have been a book on its own. But two for one isn’t so bad, either.

The Backup Men (1971) Nothing makes a whole lot of sense in any of the Mac and Padillo plots. It’s impossible that all these mysterious villains keep forcing Padillo to return to service as bodyguard or assassin when he doesn’t really want to.

However, over 200 pages in, when the team is on a search and kill mission in a mostly deserted San Francisco office building, Thomas gives us another perfect vignette. It must be stressed that the following has nothing to do with plot, but exists simply because Thomas wanted to write this character.

The lighted door was half frosted glass and half wood. Carefully lettered in black on the glass was “The Arbitrator, Miss Nancy deChant Orumber, Editor.” Padillo motioned us to the other side of the door where we flattened ourselves against the wall. He took up a similar position next to the door knob, reached for it, turned it, and flung the door open. It banged against something inside the office. We waited, but nothing happened. We waited some more and then a woman’s voice asked in a cool, polite tone, “May I help you?”

She wore a gray leghorn hat with a wide brim and a narrow white band that had artificial flowers attached to it. Pink roses, I think. She sat behind an old but carefully polished oak desk which was covered with what seemed to be galley proofs. Two sides of the room were lined with bookshelves that contained bound copies that had The Arbitrator lettered on them in gold ink below that the year of their issue. They went back all the way to 1905.

She looked at us with unwavering bright blue eyes that were covered with gold-rimmed spectacles. Her hair was white and she held a fat editor’s pencil in her right hand. Next to her on a stand was an L.C. Smith typewriter. There was a black phone on the desk and against the outer wall there were three cabinets that the door had banged against. Everything was spotlessly clean.

She asked again if she could help us and Padillo hastily stuck his automatic back in his waistband and said, “Security, ma’am. Just checking.”

“This building hasn’t had a night watchman since nineteen-sixty-three,” she said. “I do not think you are telling the truth. However, you seem too well dressed to be bandits, especially the young lady. I like your frock, my dear.”

“Thank you,” Wanda said.

“I am Miss Orumber and this is my last night in this office so I welcome your company although I must say that well brought up young ladies and gentlemen are taught to knock before entering. You will join me in a glass of wine, of course.”

“Well, I don’t think that–” Padillo didn’t get a chance to finish.

“Nonsense,” she said, rising and moving over to one of the filing cabinets. “There was a time when we would have champagne, but–” She let the sentence trail off as she brought out a bottle of sherry, placed it on the desk, returned to the file cabinet, and produced four long-stemmed glasses which she polished with a clean white cloth.

“You, young man,” she said to me. “You look as though you may have acquired a few of the social graces along the way. There’s character in your face. Some would probably call it dissipation, but I choose to call it character. You may pour the wine.”

I looked at Padillo who shrugged slightly. I poured the wine and handed glasses all around.

“We will not drink to me,” she said, “but to The Arbitrator and to its overdue demise. The Arbitrator.” We sipped the wine.

“In nineteen-twenty-one a man sent me a Pierce-Arrow. A limousine. The only condition was that I include his name in that year’s edition of The Arbitrator. A limousine, can you imagine? No gentleman would present a lady with a limousine unless he also provided a chauffeur. The man was a boor. Needless to say his name was not included.”

She had a lined, haughty face with a thin nose and a still strong chin. She could have have been a beauty fifty or sixty years ago, one of those tall imperious types that Gibson once drew.

“What is The Arbitrator,” Padillo asked, “San Francisco’s social register?” I think he was trying to be polite.

“Not is, young man, but was. It ruled San Francisco society for nearly forty years. I have been its only editor. Now society in San Francisco is no more and after this edition, neither is The Arbitrator.”

She finished her drink in quick, tiny sips. “I shan’t keep you,” she said, moving around her desk and lowering herself into the chair. “Thank you for coming.”

We turned to go, but she said, “Do you know something? Today is my birthday. I had quite forgotten. I am eighty-five.”

“Our best wishes,” I said.

“I’ve edited The Arbitrator since nineteen-o-nine. This will be the last edition, but I said that, didn’t I? May I ask you something, young man? You with the brooding eyes,” she said, nodding at Padillo.

“Anything,” he said.

“Can you think of a more ridiculous way to spend a lifetime than deciding who should or should not be considered members of something called society?”

“I can think of several,” he said.

“Really? Do tell me one to cheer me up.”

“I’d hate to spend a lifetime worrying about whether I belonged to something called society.”

She brightened. “And the bastards did worry, didn’t they?”

“Yes,” Padillo said. “I’m sure they did.”

The Porkchoppers (1972) Thomas tries out third-person for the first time. It suits him well: a bird’s-eye view gives him even more room for digressions, descriptions, and vignettes.

The topic is a union election. The White House has a stake in the outcome, as do the fixers, the bagmen, and of course two unforgettable candidates, Daniel Cubbin and Sammy Hanks.

Daniel Cubbin looked as if he should be president of something, possibly of the United States or, if his hangover wasn’t too bad, of the world. Instead, he was president of an industrial labor union whose headquarters was in Washington and whose membership was up around 990,000, depending on who did the counting.

Cubbin’s union was smaller that the auto workers and the teamsters, but a little larger than the steelworkers and the machinists, and since the first two were no longer in the AFL-CIO just then, it meant that he was the president of the largest in the establishment house of labor.

Cubbin had been president of his union since the early fifties, falling into the job after the death of the Good Old Man who was its first president and virtual founder. The union’s executive board, meeting in a special session, had appointed the secretary-treasurer to serve as president until the next biennial election. As secretary-treasurer, Cubbin had spent nearly sixteen years carrying the Good Old Man’s bag. After he was appointed president, he quickly learned to like it and soon discovered that there were a number of persons around who were anxious and eager to carry his bag, and this he particularly liked. So he had held on to the job for nearly nineteen years, enjoying its perquisites that included a salary that had climbed steadily to its current level of $65,000 a year, a fat, noncontributory pension scheme, a virtually nonaccountable expense allowance, a chauffeured Cadillac as big as a cabinet member’s, and large, permanent suites in the Madison in Washington, the Hilton in Pittsburgh, the Warwick in New York, the Sheraton-Blackstone in Chicago, and the Beverly-Wilshire in Los Angeles.

Over the years Cubbin had faced only two serious challenges from persons that wanted his job. The first occurred in 1955 when a popular, fast-talking vice-president from Youngstown, Ohio, thought that he had detected a groundswell and promptly announced his candidacy. The Youngstown vice-president had received some encouragement, but more important, some money from another international union that occasionally dabbled in intramural politics. The fast-talking vice-president and Cubbin fought a noisy, almost clean campaign from which Cubbin emerged with a respectable two-to-one margin and a permanent grudge against the president of the union that had meddled in what Cubbin had felt to be a sacrosanctly internal matter.

Cubbin was a little older in 1961 — he was fifty-one by then — when for the second time he detected signs of opposition. This time they came from a man that he himself had hired, the union’s director of organization who, after getting his degree at Brown in economics, took a job as a sweeper in a Gary, Indiana plant (an experience he still had nightmares about) and who possessed, along with his degree, the conviction that he was destined to be the forerunner of a new and vigorous breed of union leadership, the kind that would be on an equal intellectual footing with management.

Cubbin could have fired him, of course. But he didn’t. Instead he placed a call to the White House. A week later the director of organization was awakened at six-thirty by a call from Bobby Kennedy who told him that the President needed him to be an assistant secretary of state. Not too many people were saying no to the Kennedys in 1961, certainly not the director of organization for Cubbin’s union who was then only thirty-six and terribly excited about being chosen to scout for the New Frontier. Later, when Cubbin had a few drinks, he liked to tell cronies about how he had buried his opposition in Froggy Bottom. He did an excellent mimicry of both Bobby Kennedy and the director of organization.

In “With ‘Joe Hill’ and the Men of Steel” in the Washington Post (Nov. 16, 1976), Thomas writes about some of his history with unions. At times it reads just like the excerpt above.

The invitation was hand-written in brown ink and it wanted to know whether I wouldn’t like to have beer and hot dogs in Santa Monica with Ed Sadlowski, the 38-year-old Chicago maverick who was running hard for the presidency of the 1.5 million-member United Steelworkers Union.

Being president of the steelworkers is a nice job that, when I last looked, paid $75,000 a year and offered fringe benefits comparable to those enjoyed by the Shah of Iran. It wasn’t difficult to understand why Sadlowski would want it. What was difficult to understand was why he would want to have beer and hot dogs with me since I had once spent a wild and wacky two months of my life [in 1965] trying to prevent Sadlowski and his crowd from dumping David J. McDonald from that very same post.

Despite my efforts, or perhaps because of them, McDonald merrily lost…

The text then gets smudged and hard to read. Later on Thomas says that the current bunch are “tabby cats” compared to the squad Walter Reuther sent in to take down McDonald. Lurking among those Reuther UAW agents was Robert A. Maheu, the “ex-FBI agent who went on to manage Howard Hughes’ Las Vegas empire and served as contact man for the CIA when the geniuses in Langley decided they needed Mafia help in assassinating Fidel Castro….”

These days, The Porkchoppers has lost some of its power to shock, but at the time it must have been pretty racy indeed.

Boone had started small in Chicago, first investing a fair amount of capital in several white-occupied apartment buildings…

…then buying into a small construction business. Boone knew little or nothing about the construction business, but he knew all there was to know about payoffs and bribes and kickbacks and so his business began to flourish with the collective blessing of various city employees who bought new cars or had their kids’ teeth straightened thanks to Boone’s generosity.

Indigo Boone then went into politics, starting small and mildly meek at the precinct level and working his way up the Democratic party ladder, largely by doing those onerous chores that nobody else wanted to fool with, until he was now something of a minor power with excellent connections downtown.

Prior to 1960 Boone had helped steal a few elections, but it had been mostly minor stuff that had involved no more than sending some extra Democratic state legislators down to Springfield. But on the night of the election of 1960 the word came down to Boone that they would need a few additional Kennedy votes. Boone found them here and there, doing what he regarded as no more than his usual workmanlike job. But as the night wore on, additional word came down that more and more Kennedy votes were needed, that in fact a whole raft of them was needed, that indeed a deluge of Chicago Kennedy votes were needed to offset the downstate trend.

Boone found them. At least he found a lot of them and some said most. He invented new ways to filch precincts right out from under the noses of the Republican poll watchers. He improvised foolproof means of inflating the actual Democratic vote. He fell back on time-honored methods and voted the lame, the sick, the halt and the dead. He even, some said, managed to corrupt the voting machines themselves. He sped from polling place to polling place that night in a squad car, its siren moaning hoarsely, its top light flashing, giving counsel, advice, and instructions to the party faithful and buying what was needed from those who were not so faithful, peeling off fifty- and one-hundred-dollar bills from a roll that one prejudiced observer later claimed was “as big as a cantaloupe.”

Afterward, there were those partisans who claimed that Boone’s efforts had saved the nation from Richard Nixon, at least for a while. Illinois went Democratic by 8,858 votes out of the 4,746,834 that were cast for the two major parties. “Well,” Indigo Boone had said later, “when they called up and told me they needed some more Kennedy votes, why I just scurried around and got them some more, about nine thousand more, if I recollect right.”

Mickey Della is another one of the fixers, a hired gun to dream up dirty tricks.

Hanks was now accusing Cubbin of having sold out the union…it was strong stuff carefully written in an awful, florid style to make sure that it would be both broadcast and printed.

“Who writes this crap for Sammy?” the AP man asked The Wall Street Journal reporter.

“Mickey Della, I guess.”

“I thought so.”

“Why?”

“Only a real pro could make it this bad.”

After answering a few perfunctory questions, the press conference ended and Sammy Hanks left the large hotel room on Fourteenth and K Streets and headed down the hall followed by a heavy, stooped, shambling gray-haired man whose bright blues eyes glittered balefully from behind bifocal glasses with bent steel frames. The man had his usual equipment consisting of a Pall Mall cigarette parked in the corner of his mouth underneath a stained, scraggly gray mustache and a newspaper tucked under his arm. He was never seen without either a cigarette in his mouth or a newspaper under his arm because he was addicted to both. He smoked four packs of Pall Malls a day and bought every edition of every paper published in whatever city or town he happened to be in. If asked about his addiction to newspapers — he could never pass a stand or a street seller without buying one — the man always said, “What the hell, it only costs a dime and where else can you buy that much bullshit for a dime?”

The man was Mickey Della…

…He was a professional political press agent, or public relations adviser, or flack, or whatever anyone wanted to call him, he didn’t mind, and he was without a doubt the most vicious one around and quite possibly the best and he felt right at home working for Sammy Hanks.

He had been at it for more than forty years and for him it contained no more surprises, but he was hooked on it now, as addicted as any mainliner is to heroin. Mickey Della needed politics to live and he lunched on its intrigue and dined on its gossip. Its heartbreak provided him with breakfast…

…He had learned to use radio in the thirties and television in the fifties and he used them skillfully in a nasty, clever way that assured maximum impact…

…But Della remained essentially a newspaper man, a muckraker, an exposer of vice and wrongdoing, a viewer with alarm who had never got over the feeling that almost any evil could be cured by ninety-point headlines. And that was the principal reason that he was working for Sammy Hanks, because it was going to be a print campaign, as dirty, nasty, vicious, and lowdown as one could hope for and since it might possibly be the last such campaign ever held, Mickey Della would almost have paid to get in on it. Instead, he had lowered his usual fee of $66,789 to $61,802. Della always quoted his fee in precise amounts because he figured exactitude served as balm to the people who had to pay the bill.

Seaching for way to derail Cubbin’s campaign, Della begins his work in earnest:

Sunday was feast day for Mickey Della. It was the day that he rose at seven to devour The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Sunday Star, The Baltimore Sun, and the New York Daily News in approximately that order.

Della lived in the same large one-bedroom apartment on Sixteenth Street N.W. that he lived in since 1948. It was an apartment from which two wives had departed and whose goings Della had scarcely noticed. Now he lived alone, surrounded by hundreds of books, some mismatched but comfortable furniture, and six green, five-drawer filing cabinets that were crammed with articles and features that Della had ripped from newspapers and tucked away for future reference.

The apartment was cluttered, but not messy. The ashtrays were all clean, except for the one that Della used as he read his twenty-five pounds or so of newspapers. Only one coffee cup was visible. An old wooden desk with an equally old typewriter in its well had no litter on its surface. Della had cooked his own breakfast that morning, but there was no evidence of it in the kitchen. His bed was made and his pajamas were hung neatly behind the door of the bathroom whose tub was innocent of a ring. It was the apartment of someone who had lived alone long enough to learn that it was easier to be neat than not.

At noon Della crossed to the phone and dialed the home number of the man he bought his liquor from. “Mickey Della, Sid…I’m fine. Sorry to bother you on Sunday but I want to place a standing order with you and I’ll be out of town for a few days…Yeah. What I want is a fifth of real cheap bourbon, I don’t care what kind, to be delivered personally and gift wrapped to the same guy every day for the next month. Now he’s going to be out of town most of the time so you’re going to have to arrange it with American Express or Western Union or whoever you work it through…Yeah, it’s kind of a joke. I want it to start today, if possible. He’s in Chicago. Okay. Now I want the card to read, ‘Courage, a Friend.’ That’s all. Hell, I don’t even remember whether they sell booze in Chicago on Sunday. It’s not famous for its blue laws….Yeah, well, the guy I want you to send it to is Daniel Cubbin. Today and tomorrow he’ll be at the Sheraton-Blackstone in Chicago. Thanks, Sid.”

Della chuckled as he went back to his newspapers. Later there would be needling harassments that would be far better and much more vicious. But it was okay for a start and just right to set the tone for another Mickey Della campaign.

The Porkchoppers is a masterpiece that should be included on any list of this decade’s best thrillers. I’ve read it half-a-dozen times and it just keeps getting better. It’s not overdone, but rolls gently and smoothly through the mud, coming to a quiet rest on the far fencepost, sighing with irrevocable melancholy.

As with The Fools in Town Are on Our Side, there is an extraneous story: rent-a-killer Truman Goff has no good reason to be included. (Admittedly, I’m the kind of skeptical soul that wonders if Taylor Henry’s murder was necessary in The Glass Key.) Probably Thomas thought he needed some murders to sell the book as a thriller, and maybe he was right.

Thomas has found his stride and all the remaining books under the Thomas byline are great.

If You Can’t Be Good (1973) This volume is almost never mentioned by fans or commentators, but it has a tighter plot than most, a satisfying climax, and a superb reveal about the title. Thomas obviously writes himself as Deke Lucas, the cynical, nonviolent researcher who spends most of his time in libraries and exchanges witty barbs with his girlfriend.

The Kennedys turn up again when Lucas tells his personal history. There’s no doubt that Thomas was a liberal. In the Carmody article, it says that Thomas “…was one of the three cofounders of the Nigerian Democrats for Adlai Stevenson in 1960.” There’s also no doubt that Thomas goes after Democrats whenever he can! Of course he does this because he knew that both sides were dirty. Here the titles of Lucas’s reports sound like chapter titles in Warriors For the Poor.

In late 1959 I had been a candidate for a doctoral degree in history at the University of Colorado when Bobby Kennedy had swung through the West looking for people who might like to see his brother nominated President. Although only twenty-one at the time and a nominal Socialist, I had set up an organization that called itself Republican Students for Kennedy. It had made a lot of noise, but not enough to prevent John Kennedy from losing Colorado in the 1960 election by nearly 62,000 votes. After twelve years in government, I think I’m an anarchist.

But the Kennedys, devout believers in the spoils system, had been grateful for my efforts and so I was invited to Washington. When I arrived in early February of 1961 nobody was quite sure what to do with me so they made me a $50-a-day consultant and assigned me to something called Food for Peace, which was run out of a small suite in the old Executive Office Building next door to the White House by a young ex-congressman named George McGovern who didn’t quite know what to do with me either.

It was finally decided that since I was a budding historian it would be nice if I made a historic record of the first shipment of Food for Peace from the time that it left Baltimore with appropriate fanfare to when it entered the bellies of those whose hearts and minds it surely would win to Democracy’s side. I suppose everyone was still a bit naïve back in 1961.

The first shipment of food was 300 tons of wheat destined for the bellies of the citizens of one of those countries on the west coast of Africa that had just shrugged off a couple of hundred years of British colonial rule. A third of the wheat disappeared into the black market the same day that it was unloaded. The rest of it just vanished only to turn up a few weeks later when a Dutch freighter, flying a Liberian flag of convenience, dropped anchor in Marseilles.

Some six weeks after that, selected elite units of the new African nation’s army were sporting the French-made MAT 49 nine-millimeter submachine guns and I arranged to to have some awfully good pictures of them which I turned in with my 129-page report that I entitled, “Where the Wheat Went, or How Many 9mm Rounds in a Bushel?”

After that I somehow became an unofficial Cupidity and Corruption Specialist, always temporarily inflicted upon one government agency or another that had managed to get itself into hot water. I usually pried and poked for around for two or three months, digging though records and asking questions and looking grim and mysterious. Then I would write a long report that invariably told a rather sordid tale of greed and bribery on the part of those who sold things to the government and of avarice in the hearts of those who bought them.

And almost always they sat on my reports while somebody else scurried about and patched things over. The reports of mine that did surface were major scandals that were already bubbling so fierecely that it was impossible to keep the lid on. Of these the Peanut Oil King Affair comes to mind. So does the one where some Madison Avenue sharpies ripped off the Office of Economic Opportunity. That one I entitled, “Poverty is Where the Money’s At.”

Thomas never goes overboard with metaphors, but he takes some pride in describing the eyes of powerful men. They are usually ice gray. A few pages later Lucas meets Frank Size, the news columnist offering Lucas a job.

If contempt had a color, it would be the same shade of gray as his eyes, the pale, cold, glittering gray of polished granite in winter rain.

The Money Harvest (1975) While Truman Goff was extraneous in The Porkchoppers, the killers in The Money Harvest make sense as pointed social commentary, even though they are not necessary for the political plot. Perhaps some would brand Thomas a racist for documenting the way rich whites talk about poor blacks without any obvious liberal qualifiers, but I believe he is just being society’s stoolie, warning us about what really happens.

Wheat futures sound like a boring topic for a thriller, but Thomas ratchets up the tension even as he teaches us how the marketplace really works. Chapter 25 is one of the most informative segments I’ve ever read in genre fiction. As far as I can research, it is all true: Jesse Livermore, the Russian commodities scandal of 1972, Mort Sosland and The Southwestern Miller, Butz and Palmby at the Department of Agriculture.]

It was called the Hope Building, and Pope wondered if it offered any to those who rented its offices. It was a narrow, shabby, nine-story building just south of K Street on Fifteenth, which is bordered on the west by McPherson Square. At ten o’clock on the morning of the Fourth of July there were only five people in the square. Four of them were men who were asleep or passed out on the grass. The fifth was an elderly woman who sat on a park bench and talked to herself while she fed the pigeons out of a brown paper sack.

The lobby of the Hope Building smelled of vomit and Lysol and cheap cigars. There were two elevators, but one of them was decorated with an “Out of Order” sign. The sign seemed permanent. There was some green paint on the walls of the lobby that was just beginning to peel. Somebody had thrown up on the floor and a bucket and a mop stood next to the vomit, but nothing had yet yet been done about it.

Pope skirted the vomit and punched the elevator’s up button. When it came, he got in, and punched the number seven button. The elevator’s doors closed and it started moving up, but slowly and with what seemed to be muttered protestations.

At the seventh floor the elevator door clanked open and Pope moved down the hall, guided by the flaked gold paint of an arrow that claimed rooms 701 and 721 were down that way. He stopped in front of the door that had 713 painted on it in black numerals. Beneath the numerals was another painted sign that said, Commodity Jack’s Green Sheet, Inc. Beneath that in smaller letters was, John H. Scurlong, President. Pope knocked and while waiting for somebody to open the door or say who’s there or come in, he checked Commodity Jack’s neighbors. To the left was William Rice, Jobber and Manufacturer’s Representative. To the right was something called Metropolitan Industries, Inc. Across the hall was Sally Simmons Real Estate and Insurance. Pope wondered if they had all managed to scrape up their July rent.

It wasn’t until Pope knocked the second time that something happened behind the door. A bolt was drawn. A key was turned. Another bolt was drawn and still another key was turned. The door opened perhaps and inch and something blue looked out at Pope. He decided that it was an eye. The door opened wider and Commodity Jack Scurlong said, “Now you’d be Jake Pope, wouldn’t you?”

He wasn’t very tall, about five-four, and he wasn’t very heavy, about a hundred pounds if he kept his shoes on, but he was all dressed up and he moved quickly with a funny little prance. He was very old, although he had a curiously young voice, high and light, almost a tenor. Once started, he was hard to shut up.

“Mr. Scurlong?” Pope said.

“Come in, lad. Come in. Ancel Easter said you’d come calling this morning, not that I get many visitors, especially on a holiday like this, but I told Ancel that I’m still on the job seven days a week, just like I’ve always been, because in my business you’ve got to keep your eyes open all the time or the bastards’ll sneak up on your blind side. Now let’s have a cup of coffee, how does that sound?”

“Fine,” Pope said, “It sounds fine.”

“You a drinking man?”

“Sometimes.”

“I take mine this time of morning with two cubes of sugar and a good big slug of straight bourbon, how does that sound?”

“Great,” Pope said.

Commodity Jack reached inside his coat and produced a silver flask. “Holdover from prohibition, lad, now those were the days, I’ll tell you; some real shenanigans going on then. Ever hear of Jesse Livermore?”

“Never did.”

“The cotton king.”

“Doesn’t ring a bell.”

“Old Jessie cornered cotton his first time out, but of course that was in ought-eight, not the twenties. Pity about old Jesse.”

“Why a pity?”

“Walked into the Sherry-Netherland’s men’s bar, Thanksgiving eve it was, all dressed up, grey flannel suit, brand-new shoes, nice blue foulard, blue tab-collar shirt, gold pin, ordered a dry martini, drank her down, walked into the men’s room, and blew his brains out. November 28, 1940. Sorry to hear about it. Distressed. Here’s your coffee.”

“Thanks very much,” Pope said.

The telephone rang. Commodity Jack put down his own cup, picked up the phone, said hello, and then started listening. He picked up a yellow pencil and made notes as he listened. Pope looked around the room while he sipped at his bourbon and coffee. It wasn’t a big room, but neither was it small. It was about the size of what you can get at a Holiday Inn for $32 on a slow night.

One wall was covered with maps. There were maps of the United States, of Russia, of India, of China, of the world, of Argentina, of Africa, and of Australia. There were big maps and little maps and maps that seemed to have been torn from the National Geographic and Scotch-taped on top of other maps. Below the maps was a Reuter’s newsprinter that stuttered and spoke every few minutes. Next to the newsprinter was a radio, a Sony, with lots of dials and knobs and bands that looked as if it could pick up either Moscow or the local police calls, depending upon one’s mood. Across the room was a bookcase that covered the entire wall and was crammed with books and pamphlets and old copies of the Congressional Record and newspapers and magazines. On the floor was a four-foot-high stack of back copies of the New York Journal of Commerce. The wall nearest the corridor was lined with metal, four-drawer filing cabinets, some green, some gray. Just enough space was left for the office door, although it could be opened only partway before it banged into a cabinet. The door itself had four Yale locks and three bolts.

In the middle of all this, near the room’s single window, was the desk. It was an old desk, scratched and scarred, made out of some dark wood and its surface was covered with graphs and charts and clippings and an electric calculator and three telephones, one of which Commodity Jack Scurlong still held to his ear. Next to the desk was the small table that held the electric kettle and the coffee stuff. There was a swivel chair behind the desk. The only other chair in the room was the wooden one with the straight back that Pope sat in.

The only neat thing in the room was Scurlong himself. He wore a white suit that looked as if it were mede out of linen with narrow shoulders, a pinched-in waist, and a belt in the back. Pinned to its lapel was the bud of a red rose. He wore a blue striped shirt with white cuffs and collar. The cuffs were kept closed by gold cuff links and he shot the cuffs every few moments out of what seemed to be nervous habit. His tie was narrow and bright blue and his shoes were black-and-white wing tips. Commodity Jack Scurlong, Pope decided, was something of a dandy.

He must be at least seventy-five, Pope thought, maybe even eighty. But he doesn’t look it. Maybe it’s the way he moves.

Even while he was just listening on the phone Commodity Jack was in action. He shot his cuffs, and winked and smiled, made notes, sipped at his coffee and bourbon, found a comb and ran it through his long, white hair, made some more notes, nodded, grinned, and even smirked, made another note, fiddled with some papers on his desk, pulled at his nose, patted his pockets, found a cigarette, lit it, blew three smoke rings, made a note, winked at Pope, shrugged, took off his rimless glasses, breathed on them, polished them with his tie, put them back on, made another note, and fidgeted constantly as though afraid to sit still.

Scurlong had a thin, busybody face with a little black mustache that contrasted nicely with his white hair. His eyes were blue, sky blue perhaps, and shiny hard. They darted quickly about, noticing this and registering that. The face itself was deeply lined with cracks and tiny crevasses, like a piece of fine old rag paper that had been wadded up and then carelessly smoothed out. He had a pink nose that turned rosy at the tip and beneath the little black mustache was a small mouth that couldn’t be called prim because the little black mustache its ends kept twitching up too much. His teeth were white and shiny and they may not have been his own, but if they were false, they didn’t seem to bother him. There wasn’t much to his chin and this may have bothered him some because every once in a while he would lift it up and thrust it out and hold there for a while until he got tired, or forgot about it.

It was a smart face, Pope decided, maybe not wise, but certainly clever. It was also the face of someone who had made a few mistakes over the years, but refused to brood about them. Pope didn’t think that Commodity Jack Scurlong looked like someone who had much more than a nodding acquaintance with regret.

Finally, the old man said, “Thanks very much,” and hung up the phone. He looked at Pope. “London,” he said.

“On the phone.”

Commodity Jack looked at his watch. “Calls every day about this time. Later over there, you know. Time change. Market just closed. Expensive, though, these calls. Terrible phone bill. Ghastly. Well, now, Ancel said you want a crash course. Never heard the phrase before. Figured it out. Means intensive instruction, right?”

“Right.”

“You interested in going into the market?”

“No. I’m interested in finding out about it, though.”

“Ever play the stock market?”

“Yes. A little a few years back.”

“Never fiddled with commodities, though.”

“No.”

“Thought not. I can tell. Don’t know how, but I can. Look at a chap and tell whether he’s been in commodities or had gonorrhea. Don’t know why, but I can. Never had the clap, did you?”

“No,” Pope said, “I never did.”

“See. Some kind of second sight. Useful sometimes. Well, where should we start? Better have a dab more of this first.” He reached into his breast pocket, hopped around the desk, and poured another generous jolt of bourbon into Pope’s half-empty cup. “Second wing. Fly now. Well, commodities. What are commodities, Mr. Pope?”

“They’re various agricultural products, wheat, corn, oats, barley, soybeans, cotton, things like that. In recent years they’ve included other items. Frozen orange juice, Silver. Lumber. Plywood, and so forth.”

“And what are done with these commodities?”

“Well, they’re bought and sold.”

“Where?”

“In various exchanges. Let’s see. There’s the Chicago Board of Trade, it deals in wheat and soybeans and stuff like that. And the Chicago Mercantile Exchange which goes for eggs, live cattle, pork bellies, and sorghums, I think. Then there’s New York and Kansas City and other exchanges around the country.”

“And who does the buying and selling?”

“Brokers acting for their clients. Professional traders with the big companies. Speculators.”

“Speculators, you say?”

“Yes.”

“Nasty word, isn’t it? Spec-u-la-tors. Makes you think of shifty-eyed chaps, dollar signs on their vests, big jowls, big cigars, fists full of money. Diamonds on their pinkies. Chaps like that. Terrible.”

“Nobody seems to mind,” Pope said.

“Mind what?”

“Speculators in the commodity markets. You invest in the stock market, but you speculate in the commodity market. Why?”

“Excellent point. First-class point. Good mind, sir. Well, now, you can buy a share of stock and it’s yours to hold and keep forever. It can go down, up, or stay the same forever. But it’s yours. Right?”

“Right.”

“It’s an in-vest-ment. But let’s take five thousand bushels of wheat. That’s what’s called a futures contract. You go to your commodity broker. You say, ‘My Uncle Orville out in Montana’s got a wheat farm and he tells me wheat’s going through the ceiling. How can I cash in on this wonderful piece of inside dope?’ Well, sir, you make a down payment on 5,000 bushels of wheat. That’s called a margin. Your down payment is about 75 cents a bushel. Wheat’s selling for say, $5 a bushel. Terrible price. Your margin is about fifteen percent. Used to be less, but wheat got volatile, brokers got burned, margin went up. Clear so far?”

“Perfectly,” Pope said.

“Okay. But your uncle in Montana told you that wheat wasn’t going up right away, it was going up in maybe two or three weeks. Big jump then. But you want to buy cheap now and sell high in the fu-ture — mark that word — fu-ture. So you make your down payment, or margin, of fifteen percent on 5,000 bushels of wheat at $5 a bushel. That’s what everybody but your uncle in Montana think’s wheat’s going to be selling for in September. That’s called a wheat future. So for a down payment of $750 you control 5,000 bushels of wheat that’s worth $25,000. Now when you signed up for your wheat, you signed a contract. You promised to accept delivery of 5,000 bushels of wheat at $5 a bushel from somebody in September. You don’t know who. You don’t really care. But it’s somebody who doesn’t give a damn what your uncle out in Montana says. This somebody, whoever he is, is selling you 5,000 bushels of September wheat at $5 a bushel. You want to know why? Because he thinks that the price of wheat’s going to drop. Of course, he’s selling something he doesn’t own. Never will own, probably. But he’s got a contract, too. He’s got to deliver that 5,000 bushels of wheat to you in September. Clear so far?”

“Sure,” Pope said.

“Well, you’ve gone long in the wheat market and the chap you bought your wheat from has gone short. That’s what it’s called. You think the price is going to rise. He thinks it’s going to fall. If it goes up enough, you sell. If it goes down enough, say to $4.50 a bushel, he steps into the market and buys 5,000 bushels of wheat at $4.50 a bushel. Now he’s already sold you 5,000 bushels of wheat at $5 a bushel. But when delivery time comes, he can pay you off with wheat that cost him only $4.50 a bushel. So he’s made 50 cents a bushel on 5,000 bushels which is $2,500. That’s off an investment of $750, which was his margin or down payment. Not bad, huh?”

“Not bad,” Pope said.

“Ah, but suppose the price of wheat went up, like your uncle out in Montana said. When you bought your September wheat it was $5.00 a bushel. But it goes to $5.50. So what do you do? You sell. Now who buys it? Well, the chap who promised to deliver you 5,000 bushels of wheat has still got to do it. It’s in his contract. He sold you something that he didn’t own. He went short. Now he has to go out and buy it. But what does he find? Five dollars and fifty cents a bushel for wheat. That’s what. So he has to come up with the extra fifty cents a bushel and instead of making $2,500 on his contract, he loses that much.”

“You should write a book,” Pope said.

Commodity Jack shook his head. “Spec-u-la-tion is gambling pure and simple. You’re betting that the price of something that you never see and never own will rise or fall. Back in sixty-four the value of all futures contracts was a little over $60 billion. Now, it’s around $340 billion. It’s getting too big. Too fat.”

“What’s going to happen?” Pope said.

“Collapse. Disaster. A wipeout. Maybe next year or the year after. Total ruin. Awful to think of. They excuse speculation, of course. Say it provides a liquid market. Pure poppycock. Crap game, that’s what it is. Look at what Russians did. Smart. Clever. Mean, too. Hoodwinked everybody. Especially chaps at Department of Agriculture. Poor sods. Russians come in. Take out checkbooks. Buy 333 million bushels of wheat. More than 246 million bushels of corn. Barley. Sorghums. Soybeans. God knows what. Bought wheat at $1.67 a bushel. Cash on the barrelhead. Poor old Nixon out in San Clemente. He announces big deal. Wonderful news. Russkies going to buy $750 million worth of U.S. grains over next five years. They’d already bought $500 million worth and he didn’t even know it.”

“Somebody must have known it,” Pope said.

“That was back in seventy-two,” Commodity Jack said, shaking his head. “Everybody in the commodity market. Cab drivers. Little old ladies. Doctors. Bartenders. People like that. All going short. Wheat selling for $1.67. Everybody swore it would go down to $1.47. Maybe even $1.40. Everybody got fooled. By year’s end it had hit $2.70 and was still climbing.”

“Nobody went long, huh?”

Commodity Jack tapped his thin chest. “My people. I told ‘em to go long. Curious thing. Kept getting these calls from London. Chap told me his name was Mr. Smith. Nice-sounding chap. Told me every move the Russkies made. Checked it out. Found it true. Put it in the Green Sheet. My people cleaned up. Wretched business.”

“This guy Smith. Did he tell anyone else?” Pope said.

“Told a chap out in Kansas City. Mort Sosland. Editor of something called The Southwestern Miller. Kept calling him, too. Mr. Smith, I mean. Must have run up a tremendous phone bill. Long way from London to Kansas City. Never did find out who Smith really was. Most knowledgable chap though. Probably Chinese.”

“So what happened?”

“The Russkies slickered us. That’s what. All legitimate. Cost taxpayers, of course. About $300 million in shipping subsidies. That’s Department of Agriculture’s fault. Terrible incompetence. Unbelievable. Senate got mad about it. Called policy inadequate, shortsighted, dictated by outmoded prin-ci-ples. Strong language.”

“Who’s fault was it?”

“Old man Butz. Secretary of Agriculture then. Chap named Palmby, too. He took a nice job with a big grain firm. Created lot of suspicion. Nothing proved though. Exonerated. Hah.”

“What about the Commodity Exchange Authority, the CEA?”

“Bumblers. Bumbled then, bumble now. Got tip that somebody was rigging Kansas City market. Looked into it. Spent nineteen hundred man hours on it. Lot of hours. But they spent it looking up the wrong facts. Incredible.”

“Suppose somebody wanted to rig the market, the wheat market say. How would they go about it?”