(Sarah and I had known Don and Abby Westlake for about three years when Don suddenly passed on New Year’s Eve 2008. The first version of the following was my immediate tribute and obit. The essay was then expanded and revised when the blog rebooted in 2010. A second lighter revision was made in September 2014 to coincide with the publication of The Getaway Car: A Donald Westlake Nonfiction Miscellany.)

—

Whenever I told Donald E. Westlake I wanted to interview him about his complete canon, he just shrugged, not really interested. It seemed like he loved to talk about anything but his own work.

While I didn’t get to interview him, there are 92 emails from Don saved on my hard drive. Perhaps I should have conducted my interview as a written questionnaire, for he wrote as easily as most of us speak.

This page doesn’t annotate everything Westlake published, but it does cover his major fiction. For fun, I have starred (****) my favorite books.

—

The 39 non-series books written as Donald E. Westlake begin with five hard-boiled novels. They have shocking, experimental endings and high body counts. If Westlake had only produced this opening salvo, he would still be a cult figure among those who love “tough guy” fiction.

The Mercenaries (1960) An admirable debut novel wherein a minor hood named Clay is forced to be a detective for his boss. Clay’s interrogation of Broadway mogul Cy Grildquist—both of them weirdly talking to an inoperative television set in Grildquist’s swank apartment—is a harbinger of Westlake’s mature style.

Right from the beginning, Westlake’s books are filled with page-long passages describing quotidian environments. They make no pretense of being “charismatic” or “exciting” descriptions, they are just life “as is.” The 1960s novels include detailed rundowns of New York City neighborhoods and roads: my five-borough geography is certainly better thanks to reading all of Westlake.

Hard Case Crime has reissued The Mercenaries under The Cutie, Westlake’s original and better title.

Killing Time (1961) A portrait of a fully-corrupt small town. The ending is an absolute holocaust.

361 (1962) From DW’s email: “The very nice guy who runs our local liquor store had only read my lighter stuff, till a couple weeks ago, when he read 361. I walked into the place and he gave me a funny look.” Westlake studied all his predecessors seriously: 361 includes a detailed quote from Fredric Brown in the body of the text.

Westlake’s characters have feelings, but those feelings are never celebrated at the expense of the plot. This clear-eyed attitude is refreshing and addictive, but it’s also probably why Westlake never had a breakthrough bestseller. The average reader needs more obvious sentimental emotional engagement than Westlake was willing to provide. 361 is the most extreme example of this emotional distance: Westlake himself said that it was almost a technical exercise in creating emotion without speaking of it, and cited Dashiell Hammett, Peter Rabe, and Vladimir Nabokov as inspirations for this approach. 361 has been reprinted by Hard Case Crime.

****Killy (1963) My favorite of the early novels is the unflinching tale of an idealistic union organizer turned bad via murder and a femme fatale. The political aspect owes something to Hammett’s Red Harvest and The Glass Key.

Pity Him Afterwards (1964) A crazed-killer novel from years before they were de rigueur. This is the first time Westlake places action at a summer stock theater. He told me his first wife was a pretty good actress who worked in this milieu.

Memory (date unknown beyond early 1960s, published posthumously in 2010) Not a crime novel, but a long, experimental, existential exploration unique in Westlake’s canon. I haven’t really warmed up to it yet, but I’ll keep trying. If Westlake had overseen publication I suspect he would have tightened up a few corners. The ending is tremendous.

Westlake himself was surprised when his books took a comedic turn:

The Fugitive Pigeon (1965) There are too many gangster clichés in this one and The Busy Body, but they are still funny to read today…

The Busy Body (1966) … Especially the long scene of Aloysius Engel and his worthless henchman digging up a coffin late at night.

The Spy in the Ointment (1966) A modicum of liberal politics and plenty of silly send-ups of the James Bond/Man From UNCLE era.

****God Save the Mark (1967) Westlake’s first comic masterpiece won an Edgar. The title is from Shakespeare, the last line is ideal. There are limitless confidence tricks on display here, but we never lose confidence in the author.

Westlake always preferred telling the truth to handing the reader a fantasy. While his comic novels include absurd passages, the beating heart of any good Westlake book is a commitment to the most naturalistic narrative possible. There are no Westlake books where a Hero Makes No Wrong Decisions and Gets Everything He Wants In the End.

Who Stole Sassi Manoon? (1968) The first Westlake book with exotic locales and exotic characters offers a strange conceit where three college kids kidnap an arrogant movie star and everybody ends up learning life lessons. Not so memorable, but Westlake fans will enjoy details like the names of Manoon’s dogs, Kama and Sutra.

Up Your Banners (1969) Not a crime novel, but a “comedy of controversy”: a topical (and now dated) exploration of interracial romance between teachers at a Brooklyn school.

****Somebody Owes Me Money (1969) Chester is a NYC cabby trying to collect on a bet. Classic first line: “I bet none of it would have happened if I wasn’t so eloquent.” Tightly plotted and hilarious. Also recently reprinted by Hard Case Crime.

Adios Scheherazade (1970) Not a crime novel, but a partly autobiographical exploration of how writing erotic novels for a living makes you go insane. Once in a while Westlake tries out an unusual structure: here there are 10 chapters of exactly 5000 words each, just like the sex novels the hapless narrator is supposed to be writing.

I Gave At the Office (1971) Despite being a major TV network announcer, Jay Fisher is the height of unsavvy. This text is a transcript of his testimony recounting how his “on the scene” documentation of a CIA-esque takeover of a Caribbean dictatorship resulted in an international scandal.

Cops and Robbers (1972) Written expressly to be made into a movie. Of all the Westlake books set in New York City, this is the only one that paints the town as a vicious maw of uncertain violence, like Lawrence Block’s Scudder series, Ed McBain’s 87th Precinct series, and Brian Garfield’s Death Wish.

Gangway (1973) (with Brian Garfield) Historical/Western/caper/comedy. Westlake, Garfield, Joe Gores, Lawrence Block, and some others were a tight-knit crew in this era. The back cover author photo hints at the perpetual poker game of these years. The famous story of these talented, prolific, poker-playing authors betting on a manuscript they all took turns writing while playing cards is true, but apparently they didn’t get far enough for the MS to be salable.

Help, I Am Being Held Prisoner (1974) Harry Künt—don’t forget the umlaut—is a determined practical joker and model prisoner, except that he and several other cons tunnel out to escape each night before returning by morning.

****Brother’s Keepers (1975) Not a crime novel. This magnificent book — the best under his own byline since Somebody Owes Me Money — should have been a mainstream bestseller. From DW’s email: “I have to tell you a teeny thing about the genesis of BROTHERS KEEPERS. It all began with a title; THE FELONIOUS MONKS. They would commit some sort of robbery to save the monastery. So I started it and introduced them and realized I liked them too much to lead them into a life of crime. So, to begin with, there went the title. ‘Okay,’ I said, ‘let’s see what a caper novel looks like without the caper.’ Turned out to be a love story; who knew.”

Recently Lawrence Block complained about the name change, saying The Felonious Monks was a much better title. Regrettably, I think Larry’s right.

Two Much (1975) The darkest of all the humorous crime novels tells of a tasteless greeting card author/Don Juan gradually becoming more and more nefarious. Westake told me, “I never went for John Dickson Carr,” but a chapter from Carr’s The Hollow Man is placed inside Two Much.

Dancing Aztecs (1976) One of Westlake’s most popular books; widely considered one of his most hilarious. Actually, this is a bit over the top for me; the patented Westlake “one step away from reality” touch is discarded and I miss the subtlety.

****Enough (1977) (Repackaged in 2020 by Hard Case Crime as Double Feature.) Contains two wildly different stories influenced by the author’s experience with the silver screen, a short novel “A Travesty” and a short story, “Ordo.” “A Travesty” is Westlake at his absolute best, a send up of murder mystery genre conventions that surprises and delights on every page.

“Ordo” is a wan little tale of marriage with no crimes besides Hollywood excess.

Westlake had many experiences with the movies, most of them bad. In “A Travesty” he goes after auteur theory with a rapier. The narrator is a film critic who’s being blackmailed. In this scene he tries to use an interview with famous director Big John Brant to get help with his own problem:

Q: “I’d like to ask you now a more or less specific question of technique, based on a film other than one of yours.”

A: “Someone else’s picture?”

Q: “Yes. This is a work in progress being done by a young filmmaker here in New York. I’ve seen the completed portion, and I’d like to ask you how you would handle the problem this young filmmaker has set for himself.”

A: “Well, I’m not sure I get the idea what you want here, but let’s give it a try and see what happens.”

Q: “Fine. Now, the hero of this film is being blackmailed in the early part of the picture. But then he gets rid of the evidence against himself, but the blackmailer keeps coming around anyway. He’s bigger than the hero, threatens to beat him up and so on, he even moves into the hero’s apartment, he still wants his blackmail money even though the evidence is gone. The hero doesn’t want to go to the police, because he’s afraid they’ll get too interested in him and start looking around and maybe find some other evidence. So that’s the situation, as far as this young filmmaker’s taken it. The blackmailer is in the hero’s apartment, the hero is trying to decide what to do next. Now, if this was one of your pictures, how would you handle it from there?”

A: “Well, that depends on the story.”

Q: “Well, I think he wants the hero to win in the end.”

A: “Okay. Fine.”

Q: “The question is, where would you yourself take it from there?”

A: “Well, what’s the script say?”

Q: “That doesn’t matter. That’s still open.”

A: “Open? You have to know what happens next.”

Q: “Well, that’s up to you. What would you have happen?”

A: “I’d follow the script.”

Q: “Well, they’re doing this as they go along.”

A: “They’re crazy. You can’t do anything without a script.”

Q: “Well…They’re working this from an auteur theory, that it’s up to the director to color and shape the material and so on.”

A: “Yeah, that’s fine, but you got to have the material to start with. You got to have the story. You got to have the script.”

Q: “Well…I thought the director was the dominant influence in film.”

A: “Well, shit, sure, the director’s the dominant influence in film. But you still got to have a script.”

Well, that wasn’t any help. What was I supposed to do, go ask three or for screenwriters for suggestions? Is the director the auteur or isn’t he?

I did keep trying in this vein for a few more questions, but this didn’t get me anywhere. So far as I could see, Big John Brant’s career had come down to this; he was the fellow who told the cameraman to point the camera at people who were talking. And to think how high in the pantheon I’d always placed this man.

The script. Only a hack cares about the goddam script. What I needed was to talk to a real director; Hitchcock, or John Ford, or John Huston, or Howard Hawks. What happens next? that was my question. Sam Fuller would have an answer to that. Roger Corman, even.

Castle in the Air (1980) The dedication reads, “And this one is for the guys and gals at the Internal Revenue Service.” It’s the weakest over-the-top caper novel—was it written desperately to pay a tax bill? Don’t let this be your introduction to Westlake.

Kahawa (1981) Westlake was proud of this serious caper novel set in Idi Amin’s domain. While Kahawa shows that Westlake easily could have been a Robert Ludlum-ish “international espionage”-style writer, I admit that I’m glad that he didn’t pursue this direction further.

Occasionally the (fake) title The Time Of the Hero shows up in the Westlake canon, like in the introduction to the reprint of Kahawa, where Westlake explains that Kahawa almost had that title, except, “My feeling is, if the title is too boring to read all the way through, it might keep readers from trying the novel.”

Westlake’s best leads are criminals and fuck-ups, and he knew it. Kahawa even concludes with a near-apology to the reader for having a proper hero.

The Comedy is Finished (circa early ’80s, published posthumously) Like the posthumous Memory, The Comedy is Finished received quite a few accolades. Some even go so far as to say that it is a lost masterwork.

Certain things are indeed inarguably masterful. The FBI agent and crew are kept firmly in the middle. In the hands of anyone else, these law enforcement officers would be mean, silly, or incompetent, but DEW just holds it steady without resorting to drawing a cartoon. However, the book as a whole seems pretty dated, and, frankly, the way Westlake portrays women radicals is distressing.

In general, many of his books from the late ’70s/early ’80s (like Castle in the Air and Kahawa just above, along with the lesser series under the pen name Sam Holt) just aren’t his strongest. He was having trouble gaining traction in the industry. There weren’t even any Dortmunders from ’77-’83.

Eventually, this frustrating period inspired one of his authentic masterpieces:

****A Likely Story (1984) Not a crime novel, but the ultimate insider’s skewering of the publishing industry as seen by a working writer. The narrator is the editor of a book about Christmas, and the capsule descriptions of Christmas-themed Christmas Book submissions by Stephen King, Isaac Asimov, Norman Mailer, etc., are just fabulous. A Likely Story is also a meditation on the intricacies of modern love, marriage, and family. Note the title: could this be a roman à clef?

A Likely Story pairs with the expansive novelette “A Travesty” from Enough. Their meta succeeds because Westlake understood genre conventions so well. He tells stories about the art of telling stories; the final effect, lightly vicious yet unquestionably comic, gives us tales that are among the most obviously “Westlakean” of his whole bibliography.

When he first opened a website, Westlake’s splash page was simply his phrase, “I believe my subject is bewilderment…but I may be wrong.” That phrase may not make much sense when looking at some of Westlake’s most famous books concerning cops and robbers. But that phrase makes a lot of sense when contemplating A Likely Story and “A Travesty.”

Levine (1984) Another structural experiment, offering interlinked short stories about a NYC cop with heart trouble. Only the last story is recent; the rest are from Westlake’s earliest days flogging shorts to places like Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. The terrific 12-page introduction detailing his start as a writer is collected in The Getaway Car.

High Adventure (1985) The title is a pun: there’s lots of marijuana in this book. The “over the top” feel is similar to Dancing Aztecs.

****Trust Me On This (1988) This murder mystery perpetrated and solved by members of a National Enquirer-style tabloid is a recommended for those who don’t “get” the comic side of Westlake yet. The introduction is pure Westlake:

A Word in Your Ear

Although there is no newspaper anywhere in the United States like the Weekly Galaxy, as any alert reader will quickly realize, were there such a newspaper in actual real-life existence its activities would be stranger, harsher, and more outrageous than those described herein. The fictioneer labors under the constraint of plausibility; his inventions must stay within the capacity of the audience to accept and believe. God, of course, working with facts, faces no limitation. Were there a factual equivalent to the Weekly Galaxy, it would be much worse than the paper I have invented, its staff and ownership even more lost to all considerations of truth, taste, proportion, honor, morality or any shred of common humanity. Trust me.

In her spare time, brand-new Galaxy reporter Sara Joslyn is working on a thriller called The Time of the Hero.

Tomorrow’s Crimes (1989) This pairs with Levine, as both are Mysterious Press reprints of Sixties-era work. Tomorrow’s Crimes features a few SF stories and the novelette “Anarchaos” originally published in 1967 under the name Curt Clark. “Anarchaos” is quite good and brutal, with a lead character showing the determination of Parker, although the emotional context is similar to the posthumous Memory. Of the shorts, “In at the Death” is probably the best, packing a Fredric Brown-esque punch and showcasing Westlake’s love of precise language from the very beginning:

It’s hard not to believe in ghosts when you are one. I hanged myself in a fit of truculence–stronger than pique, but not so dignified as despair–and regretted it before the thing was well begun.

****Sacred Monster (1989) A star was born in Jack Pine, the heartthrob of millions. But what price fame? This underrated book is a meditation on the craft and lifestyle of Hollywood actors. The crime element is present, but only as an afterthought. Amusingly, a Westlake nom de plume is killed off in passing: “This house, until recently owned by a television star named Holt who’d committed suicide when his series was canceled…”

Humans (1992) An intriguing book pairing with Smoke below as some sort of sci-fi or metaphysical exploration with a crime caper element. In Humans, the angel Ananayel is God’s covert operative setting up a “deniable” end of the Earth. It meanders in the middle—one wonders if he was trying to make the word-count of someone like Stephen King—but the climax is very tense and exciting. In the introduction Westlake blames Evan Hunter for encouraging him to try something on a bigger canvas.

Baby, Would I Lie? (1994) The sequel to Trust Me on This explores the world of country music and the related theme park of Branson, Missouri. The plot and musical details are successful, but maybe one go-around with the Weekly Galaxy was enough.

Smoke (1995) A cigarette corporation tries to prove that melanoma isn’t so bad and finds the secret to invisibility in the process. A burglar—yes, it’s a Westlake book—accidentally becomes the test case. Chapter 49 begins with the longest Westlake sentence: 183 words, a joke about Henry James. Westlake told me once that as much as he loved reading Anthony Powell, he worried that Powell was a bad influence on his sentence length. “Shorter sentences are usually better,” Westlake said.

****The Ax (1997) Burke Devore needs a job.

The Ax has my vote as Westlake’s masterpiece. Westlake always said he never outlined or planned too much; he just invented characters and they showed him the way. For The Ax (he told me and Sarah) he wrote the first couple of paragraphs and took it to his agent, asking basically, “Do you want to read a book about this guy?” His agent said yes and Westlake wrote the whole book in about three weeks. I will never forget Don taking The Ax off his shelf and reading us what he showed his agent:

I’ve never actually killed anybody before, murdered another person, snuffed out another human being. In a way, oddly enough, I wish I could talk to my father about this, since he did have the experience, had what we in the corporate world call the background in that area of expertise, he having been an infantryman in the Second World War, having seen “action” in the final march across France into Germany in ’44-’45, having shot at and certainly wounded and more than likely killed any number of men in dark gray wool, and having been quite calm about it all in retrospect. How do you know beforehand that you can do it? That’s the question.

Well, of course, I couldn’t ask my father that, discuss it with him, not even if he were still alive, which he isn’t, the cigarettes and the lung cancer having caught up with him in his sixty-third year, putting him down as surely if not as efficiently as if he had been a distant enemy in dark gray wool.

The question, in any case, will answer itself, won’t it? I mean, this is the sticking point. Either I can do it, or I can’t. If I can’t, then all the preparation, all the planning, the files I’ve maintained, the expense I’ve put myself to (when God knows I can’t afford it), have been in vain, and I might as well throw it all away, run no more ads, do no more scheming, simply allow myself to fall back into the herd of steer mindlessly lurching toward the big dark barn where the mooing stops.

Today decides it. Three days ago, Monday, I told Marjorie I had another appointment, this one at a small plant in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, that my appointment was for Friday morning, and that my plan was to drive to Albany Thursday, take a late afternoon flight to Harrisburg, stay over in a motel, taxi to the plant Friday morning, and then fly back to Albany Friday afternoon. Looking a bit worried, she said, “Would that mean we’d have to relocate? Move to Pennsylvania?”

“If that’s the worst of our problems,” I told her, “I’ll be grateful.”

After all this time, Marjorie still doesn’t understand just how severe our problems are. Of course, I’ve done my best to hide the extent of the calamity from her, so I shouldn’t blame Marjorie if I’m successful in keeping her more or less worry-free. Still, I do feel alone sometimes.

This has to work. I have to get out of this morass, and soon. Which means I’d better be capable of murder.

I emailed Don: “I re-read The Ax last month, and noticed for the first time the superb names of some of the addresses on Burke’s journey: Wildbury, Fall City, Nether St., Dyer’s Eddy, Erebus….Obviously, Burke has to “Devore” (devour) all these addresses to get from Halycon to Arcadia.”

His response: “That’s right. Usually I don’t mess with meaningful names for things (except comic), but that time I wanted the atmosphere to be in every comma. Not that somebody reading it needs to catch all or any of it; you don’t need to be aware of the smoke to feel a little antsy.”

A Good Story and Other Stories (1999) Enjoyable but inessential crime tales from diverse eras. Westlake didn’t consider himself a truly gifted short story writer. From his email: “Short stories have always been a secondary thing for me, and now that Alice Turner is gone from Playboy I don’t need to do them at all any more. A 70,000 word idea is much more fun than a 7,000 word idea.”

****The Hook (2000) A companion to The Ax which is almost as good. Like A Likely Story, one to be read by fellow novelists. Westlake’s ability to make unbelievable scenarios believable is on full display: maybe you, too, could kill a friend’s wife. A fun Westlake-as-crime-novel-historian moment:

“I think you gave up too quickly on the story about the guy who murdered the woman he didn’t know. I mean, nobody knew he knew her.”

Bryce cocked his head, gazing off. “You think so?”

In fact, Wayne did not. He thought the story was suited to a paperback original published around 1954, and the woman’s brother would be a gangster, probably in a gambling racket somewhere. Kill Me Slowly, it would be called.

The Hook also contains a rare self-referential moment:

He’d always been a storyteller that got the details of our world right. Not just the guns and the planes and the perfumes and the whiskeys, but the highway intersections and the histories of obscure clans and the reasons for the extinction of this or that species.

Much of his preparation had been in libraries or on the phone with experts. He had learned early on that he could phone almost anybody in the world, from the Israeli United Nations Mission to Budget Auto Rental’s main headquarters, and say, “I’m a writer working on a novel, and I wonder if you could tell me…” and people would stop whatever they were doing, answer the questions, look things up, spend as much time as he wanted, and wish him luck at the end of the call. It was one of the great secret resources of the fiction writer, that pleasure that the rest of the world takes in helping the fiction along.

****Put a Lid on It (2002) The last three non-series novels lack the superb tension of The Ax and The Hook. It’s fair to say that the Dortmunder and Parker books from this era have more weight. The best of the three is Put A Lid on It, a “political fixer” novel that is almost a Ross Thomas tribute and is funny as hell.

Money for Nothing (2003) An innocent man is drawn into an espionage net. This has the feel of something written for the movies, with a “wrong man drawn into a nefarious net” conceit going back at least to Eric Ambler. My wife started to read it and was instantly hooked, but we agreed that the book loses momentum when the honest Westlake refuses to keep tying extra knots, instead keeping the scenario realistic.

The Scared Stiff (2003) A surprise replay of the kind of “exotic locale” caper Westlake wrote time and again since Who Stole Sassi Manoon? It was first published under the pen name Judson Jack Carmichael.

There are 24 Richard Stark books with Parker as the lead. Master thief Parker is probably the greatest antihero in all crime fiction. He is unquestionably the most matter-of-fact: Parker observes his emotions from a great distance and rarely shares them with anyone else.

Some commentators on Westlake think Parker is his greatest character and that the series is his greatest work. They are easily his most influential books: Crime fiction, crime movies, and crime comics today wouldn’t be the same without Richard Stark.

The University Press of Chicago has reissued the complete set, often with valuable introductions by fellow literati. Darwyn Cooke did beautiful comic adaptions of some of the early books; my favorite Cooke is The Outfit, with all those many small heists told in varied styles.

The Hunter (1962) All the early books start in motion, with the word “When.” (Here is a collection of the opening lines.) In The Hunter, Parker is filled with a white-hot rage, destroying most of what he touches. “When a fresh-faced guy in a Chevy offered him a lift, Parker told him to go to hell,” scans as a bit strange if you know the rest of the series. The mature Parker would never tell a stranger, “Go to hell.”

It is the only Westlake book that has produced a great movie, Point Blank. From our email exchange:

EI: “I saw Point Blank on the big screen two weekends ago–Lee Marvin is great, the music is great, the sets are amazing, the babes are delicious, but your plot is nowhere to be found! Hard for me to think of another instance of such a good book making such a good movie –both really good– when the text of one is so misunderstood by the other.

“You must be kind of amazed at the Parker saga by now…40 years, right? First a pen name that no one knew was yours–cheap paperback originals–titles changed at the whim of whatever editor–Lee Marvin movies–French art movies–zillions of reprints and translations–cult classics–now new hardbound novels about the same character–“

DW: “I’ve always loved POINT BLANK sort of the way the Neanderthal mother loved that first hairless mutant: did that come from me? And I never get over being astonished at how far that original toss has sailed. In addition to the lowly origins you mentioned, there’s also the fact that it was supposed to be a one-off, that I had Parker arrested by the cops at the end of THE HUNTER, which is part of why I didn’t bother to give him a first name. A Pocket Books editor named Bucklyn Moon (honest: discovered Chester Himes) asked me if I could somehow arrange Parker’s escape and bring him back. It’s all careful planning, all careful planning.”

Westlake also told me in person that Lee Marvin agreed to participate in the movie because Marvin, “Had never seen that character before, and wanted to play him.”

The remake starring Mel Gibson, Payback, is a travesty.

****The Man With the Getaway Face (1963) Parker is in control now: when he brings home a man’s head in a box, it is because of business, not revenge. From here on out, Parker’s temperature is mostly unemotional and professional.

****The Outfit (1963) Crams as many heists as possible into single book. Every sentence rides an express train from beginning to end.

The first three Parker books form an interconnected trilogy that is surely one of the finest achievements of the genre. The next ten books are a bit inconsistent. Sometimes the scenarios are a bit gaudy or the double-crossing a bit rote. They are also all quite short. You can read them like eating cookies. Munch, munch, swallow… take another one down from the shelf…Munch, munch…

It’s worth keeping in mind that there was no cachet to the series yet. The Parker books were churned out to be read in cheap mass-market editions. In his Mystery Scene interview with Lee Server, Westlake says, “I was this anonymous guy in the middle of the night spewing out this stuff pretty fast.”

The Mourner (1963) A riff on The Maltese Falcon. At one point, Parker tortures a woman at length to get information. The scene is not really described in detail at all; it’s just part of Parker’s job that day.

The Score (1964) Can Parker take down a full town? This book has the first appearance of Parker’s occasional sidekick Alan Grofeld, the summer stock theater-owning actor/heister.

The Jugger (1965) Parker buries his mailbox (an old buddy named Joe Sheer) and trouble ensues.

****The Seventh (1966) One of the toughest of a tough series and my favorite of this ten. Westlake’s truth-telling never varies as Parker’s own stupid mistake with the cops kills off his whole crew. Parker doesn’t care, though. At the end he laughs (a real rarity) while clutching a fistful of bloody cash.

Westlake believed in putting surreal or out-of-place events in genre fiction. Not events that don’t make sense in the story, but events that don’t make sense for the writer to have written. He learned this from Dashiell Hammett, as he suggests in his essay “The Hard-Boiled Dicks”:

The English like Chandler better than Hammett because they understand him more. The ritual is firmly in control. In Hammett, in The Dain Curse, there’s a question about some money a character has, and we get this:

Rhino said, “Ain’t nobody’s business where I got my money, I got it, I got–” He put his cigar on the edge of the table, picked up the money, wet a thumb as big as a heel on a tongue like a bathmat, and counted his roll bill by bill down the table. “Twenty — thirty — eighty — hundred — hundred and ten — two hundred and ten — three hundred and ten — three hundred and thirty — three hundred and thirty-five — four hundred and thirty-five — five hundred and thirty-five — five hundred and eighty-five — six hundred and five — six hundred and ten — six hundred and twenty — seven hundred and twenty — seven hundred and seventy — eight hundred and twenty — eight hundred and thirty — eight hundred and forty — nine hundred and forty — nine hundred and sixty — nine hundred and seventy — nine hundred and seventy five — nine hundred and ninety-five — ten-hundred and fifteen — ten hundred and twenty — eleven hundred and twenty — eleven hundred and seventy. Anybody want to know what I got, that’s what I got — eleven hundred and seventy dollars. Anybody want to know where I get it, maybe I tell them, maybe I don’t. Just depend on how I feel about it.”

Now, what the hell is that all about? Chandler would have never done a thing like that. He was always too correct.

Near the end of The Seventh, Parker’s narrator somehow feels it necessary to detail a similar overly-specific money count:

He pulled open the gates and went in and rolled the amateur over on his back and went through his pockets.

Left trouser pocket, sixty-three twenties. Right trouser pocket, thirty-nine twenties and twenty-five tens. Left hip pocket, fifty-two tens and ten fifties. Right hip pocket, forty-seven twenties and nine tens and eight fifties. Right shirt pocket, forty-two twenties and four hundreds. Nothing in the left shirt pocket; that must be where the eight hundred eighty bucks had come from.

Still more. Left jacket pocket, fifty twenties and nine fifties. Right jacket pocket, fifty-three twenties and seven fifties. Inside jacket pocket, ninety-five twenties and three hundreds.

The amateur had bulged with cash, bloated with cash, overflowed with cash.

Left raincoat pocket, ninety-three twenties and seventeen tens. Right raincoat pocket, eighty twenties and fifteen fifties.

All together, seven hundreds and forty-nine fifties and six hundred two twenties and one hundred eleven tens, including the money left on the stairs.

Sixteen thousand three hundred dollars.

Now, what the hell is that all about?

The Handle (1966) An exotic island run for gambling is Parker’s score. It’s amazing how casually Westlake kills off Parker’s partners; I would have happily read more books with Salsa involved.

The Rare Coin Score (1967) Introduces Parker’s love interest Claire. A lot of times the best parts of these books are the digressions into armament and transportation. Here, Parker’s negotiation to buy an old truck is a highlight.

The Green Eagle Score (1967) This was the first Parker I read. I could not understand how dry as dust, simple, and matter of fact it was. Weren’t crime novels supposed to have a suppressed current of sentimental emotion running through them? Maybe I had better read it again…

The Black Ice Score (1968) Probably the weakest Parker, with a crew of Africans that belong over in Westlake’s comedies.

****The Sour Lemon Score (1969) Nothing goes right in this one. It’s just a blast to read. Westlake talks about this entry in the aforementioned Mystery Scene interview: “…There were two characters from the past that had to come back [for the 2001 Parker Firebreak]…So I had to re-read it…And…it sounds immodest…but I thought, you know, this is pretty good! Ha!…Also I could see a moment about two-thirds of the way through where the writer didn’t know what the hell he was doing, but kept going…Wait a minute, you’re vamping here!” I don’t see much vamping myself, although Parker does complain about driving back and forth without doing much.

Deadly Edge (1971) The first half (the heist) is more stylish and memorable than the second half (where psychos go after Parker’s new woman, Claire).

Deadly Edge was the first Parker to be in hardcover, but it doesn’t feel that different from the previous ten quickies. However, the next three hardcover books are longer and more serious.

****Slayground (1971) A stone masterpiece. Here’s the thing about the Parker series: They are believable. In this case, Parker is trapped inside a large indoor amusement park in the Midwest while the local Mafia hunts for him. This is, of course, ludicrous. But Westlake never tips the action into parody. When Parker falls into an icy stream, he needs to sleep before he can fight again. When he realizes there are just too many hoods for him to take on alone, he leaves without triumph.

Plunder Squad (1972) Parker steals some art. There are some amusing moments when he interfaces with high society a little bit. One of Parker’s crew, fat Lou Sternberg, is reading Anthony Powell. Indeed, Sternberg seems to be modeled on Widmerpool from A Dance to the Music of Time.

****Butcher’s Moon (1974) The sequel to Slayground is last, longest, and bloodiest of the series’s first run. It’s another example of how to pack the maximum number of heists into one book. Stephen King likes to quote this immortal passage:

“It was a stupid thing to kill Al Lonzini,” Shevelly said.

Parker frowned at him, looking at the coldly angry face. “Oh. They told you I did that, huh?”

Shevelly had nothing to say. Parker, studying him, saw there was no point arguing with him, and that it was no longer possible to either trust him or make use of him. He gestured with the pistol toward Shevelly, saying, “Get out of the car.”

“What?”

“Just get out. Leave the door open, back away to the sidewalk, keep facing me.”

Shevelly frowned. “What for?”

“I take precautions. Do it.”

Puzzled, Shevelly opened the door and climbed out onto the thin grass next to the curb. He took a step to the sidewalk and turned around to face the car again.

Parker leaned far to the right, aiming the pistol out at arm’s length in front of him, the line of the barrel sighted on Shevelly’s head. Shevelly read his intention and suddenly thrust his hands out protectively in front of himself, shouting, “I’m only the messenger!”

“Now you’re the message,” Parker told him, and shot him.

Max Allan Collins got his start as a professional writer with a series about a heister modeled on Parker called Nolan. Apparently he talked it over with Westlake and Westlake gave Collins his blessing. Surely Collins was thrilled when reading Butcher’s Moon: Parker meets with the politicos in the Nolan building. The postlude to the reissue of the first two Nolan stories, Two For the Money, has more information on the Nolan/Parker connection.

Eventually Collins took the “Now you’re the message” riff from Butcher’s Moon and put it in Road to Perdition, an act of minor thievery Westlake was less happy about.

****Comeback (1998) Parker’s return after 24 years is as good as any book in the series; as a bonus, it skewers evangelism, too. Comeback’s epigraph says it all about Parker’s attitude:

“The outcome you have been waiting for is assured. Continue to persevere.” —Chinese Fortune Cookie

Comeback also has my favorite lead of any Parker:

When the angel opened the door, Parker stepped first past the threshold into the darkness of the cinder block corridor beneath the stage. A hymn filtered discordantly through the rough walls; thousands of voices, raggedly together. The angel said, “I’m not sure about this.”

“We are,” Parker said.

Comeback was finished in the aftermath of The Ax. Perhaps that dark masterpiece enabled to Stark to resurface? The major Michael Mann movie Heat (which surely claims the Parker series as part of its DNA) was a hit in 1995: Was this movie also a spur to author to show the world how heisting was really done?

Some commentators have muttered that the new Parker books weren’t as good as the old ones. I disagree! The late Parkers are my favorite Parkers. There isn’t a bad page from here to the finish.

Backflash (1999) Two fully successful heists in a row! Parker is doing well since he’s back. This time he takes the money off a gambling boat.

****Flashfire (2000) Another example of the maximum number of heists stuffed into one book. The concluding chapter of Parker-cop repartee is priceless. Letting Parker walk away, the cop says, “I’ll always wonder if I could have taken you,” to which Parker replies, “Look on the bright side. This way you have an always.”

Flashfire was the source for the Jason Statham vehicle Parker. The Statham tagline that all Parker fans hate, “I don’t steal from people who can’t afford it, and I don’t hurt people that don’t deserve it,” is featured on the back of the UK movie tie-in edition of Flashfire. This is notably ironic: In the very first paragraph Parker casually bombs a gas station (with people inside) as a diversion while working on a heist occurring across town.

****Firebreak (2001) Parker unhesitatingly trains young psychopath Larry Lloyd in the finer points of murder, arson, and getting out with something from the remains of a heist gone sour.

****Breakout (2002) Parker escapes from prison. Do you really need more inducement to read this book? If so, Breakout also has Westlake’s first truly excellent black character, a professional hardcase named Williams. Previous black Westlake characters like Dortmunder’s jugger Herman X and the love interests in Up Your Banners and The Blackbird are only OK, but Williams is something else.

Williams had been happy to stick with Parker in Stoneveldt, though he would have been more comfortable if his partner had been of color. But nobody of color in that place looked to be making a key to get out of there, and Parker did. So when Parker asked him to come along, he rode with the idea, though at first with every caution. Does this guy really want a partner, or does he want somebody to throw off the sled when the chase starts?

Throughout their time together, Williams had watched the man he had known then as Kasper, waiting for him to give himself away, and it never happened. It looked at though Parker was just a guy determined to get out of that place, who’d known he couldn’t do it on his own but needed a couple of guys in it with him, and who’d decided Williams should be part of the crew. No more, no less.

Well, that was then, this was now. They were out, though still not many miles from Stoneveldt. But guards and gates and prison walls didn’t hold them any more. Williams watched Parker, thinking, I done my part, I been straight with you. I know you got me out of there, but I got you out of there, too, so what does that mean? Is this crew still together?

He was dependent on Parker, whichever way he went. It wasn’t possible to ask anything, so all he could do was stand there and watch and wait, and know that, sooner or later, they would be both going to ground, but in very different places.

****Nobody Runs Forever (2004) Just like the first three of the series, the final three books evolved into an interconnected trilogy. Westlake must have done an amazing amount of research to keep Parker’s work environment up to date over the years. The arc of crime enforcement can be traced by how hard it is for Parker to pull a heist: in The Hunter from 1962, Parker runs several small scams at New York City banks without any photo I.D., and in the final trilogy he’s constantly staying just one step ahead of post-Patriot Act law.

Of course, there’s a strong through-line too. The first scene in Nobody Runs Forever, where Parker puts down his poker cards in order to strangle a fellow thief who is wearing a wire, could have been included in any of the books from 40 years earlier.

****Ask the Parrot (2006) Westlake described this to me as, “Parker among the straights.” There are a couple of amusing goofy edges as Parker deals with a whole town of amateurs. The parrot even has a scene of internal dialogue, a successful experiment. This paragraph near the end shows Westlake at his most Stark:

There was very little time to waste here, but there was time enough for this. He would wait, and Cory would reveal himself, and Parker would kill him. He would wait, and Lindahl would come back and make some sort of disturbance, flushing Cory out, and Parker would kill him.

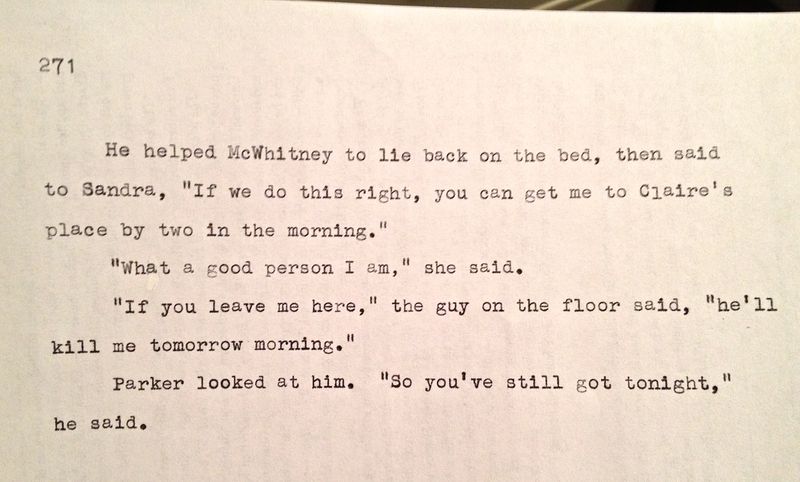

****Dirty Money (2008) Ah Christ, is it really the last one? Well, at least we had 24 of them. How does an author know when a book is done? Westlake told me that a book should end when the reader could easily write the next chapter. At the very end of Dirty Money, Parker leaves a trussed-up enemy in the hands of a recovering associate:

“If you leave me here,” the guy on the floor said, “He’ll kill me in the morning.”

Parker looked at him. “So you still have tonight.”

(end)

—

The 4 Richard Stark novels with Alan Grofeld as the lead include The Damsel (1967), The Dame (1968), The Blackbird (1971), and Lemons Never Lie (1971). I’m not sure the first three work so well: they attempt to inject some of the globe-trotting humor of Westlake into the heister ethos of Stark, and the results seem unsettled. Astonishingly, they were the first Starks in hardcover. Grofeld got there before Parker! The cover blurb for The Dame says it all: “Murder and mobsters put the finger on Alan Grofeld, Mr. Cool, when he meets up with…The Dame.” The best part of these books are when Grofeld commits heinous acts of murderous violence in the context of something that is reading as a light comedy.

After these “girl” books and the respectable Cock Robin/Macmillian imprint, Grofeld has his best turn in the brilliant ****Lemons Never Lie which is as tough as a Parker book. It used to be extremely rare indeed, published by World and blurbed by Lawrence Block’s pen name Paul Kavanagh: “The best Richard Stark ever.” In conjunction with this book’s recent reissue by Hard Case Crime, Westlake wrote on his website: “What pleases me most about LEMONS NEVER LIE is that it was the only time I can think of where I invented a plot structure. That structure, which is not an arc but three bounces, each one higher, was new, I believe.”

—

I suspect that the 15 Donald E. Westlake novels with John Dortmunder in the lead are the ones that Don’s close companions and Don himself related to the most. They document elaborate heists performed by a talented but slightly bumbling everyman. Don wasn’t bumbling — not in the slightest — but after meeting him I decided he was clearly more Dortmunder than any other Westlake character.

When people told Westlake how realistic the Parker books were, he would joke that the Dortmunders were even more realistic, since Parker could always find a place to park his car and Dortmunder couldn’t.

The Hot Rock (1970) How many times do you need to steal an emerald? Westlake had originally planned on giving Parker this assignment, but realized Parker would cut his losses and quit mid-book. He needed a thief who was fatalistic. It’s not a bad movie, but honestly Robert Redford was miscast. Westlake told me he had imagined Harry Dean Stanton as Dortmunder.

Bank Shot (1972) I like the first two Dortmunders, but they are still revving up.

****Jimmy the Kid (1974) Here we go! A masterpiece of meta. Anthony Boucher outed Richard Stark as Westlake in the New York Times, so the author responded by (sort of) combining both worlds. At one point, Dortmunder’s crew has a stroke of good luck. Dortmunder’s response? “We’ll pay for this.”

Nobody’s Perfect (1977) Stealing one painting takes a lot out of you. Structured as “The Verse,” “The First Chorus,” “The Second Chorus,” “The Bridge,” and “The Final Chorus.” The Christmas party in Dortmunder’s home is a vast celebratory canvas that carefully leads up to an all-time great punch line.

****Why Me? (1983) The franchise really starts to settle down here. At first, sidekick Andy Kelp was a dim-witted thorn in Dortmunder’s side, but from here on out, Kelp and the rest of the team consistently act like experienced pros. I think Westlake was too much of a professional himself to put up with amateurism any longer. Of course, just because they are pros, that doesn’t mean that they win.

After Chief Inspector Francis Mologna refuses a $60,000 bribe from extremists, he thinks, “You don’t get to be the top cop in the great city of New York by takin bribes from strangers.”

****Good Behaviour (1987) Oh dear, a sisterhood of Nuns who have taken a vow of silence need Dortmunder’s help rescuing one of their own. Structured as “Genesis,” “Numbers,” “Lamentations,” and “Exodus.” One of the funniest books ever written.

****Drowned Hopes (1990) A Jim Thompson-style character, Tom Jimson, shows up and puts the fear of God into everybody. What Dortmunder ends up fearing even more than Jimson is the Vilburgtown reservoir, which Dortmunder keeps intentionally and unintentionally exploring in great depth. Structured as “First Down,” “Second Down,” “Third Down,” and “Fourth Down.”

When the the crew is getting restive waiting it out in a small town upstate, Stan Murch takes a solo:

Stan had brought home a dark blue Lincoln Atlantis, a huge old steamboat of a car, which he was “fixing up” in the driveway beside the house. Along about the third day, May came out onto the porch and with her hands in a dish towel — she’d never done that before, was doing it unconsciously now — and looked with disapproval at what Stan, with help from Tiny, was wroughting.

On newspapers spread on the lawn squatted any number of automobile parts, all caked with black oily grime. The Lincoln’s huge hood had been removed from the car and now leaned against the chain-link fence like a Titan’s shield. The moth-eaten old backseat was out and lying on the gravel between the car and the street in plain sight of the entire neighborhood.

“Stan,” May said, “I’ve gotten two phone calls already today.”

Stan and Tiny lifted their heads out of the hoodless engine compartment. They were as grimy and oil-streaked as the auto parts. Stan asked, “Yeah?”

“About this car,” May told him.

“Not for sale,” Stan said.

“One, there’s no papers,” Tiny added.

Stan was about to dive back into his disassembled engine when May said, “Complaints about the car.”

They looked at her in surprise. Stan said, “Complaints?”

“It’s an eyesore. The neighbors think it distracts from the tone.”

Tiny scratched his oily head with and oily hand. “Tone? Whaddya mean, tone?”

“The quality of the neighborhood,” May told him.

“That’s some quality,” Stan said, getting a little miffed. “Down where I live in Brooklyn, I got two, three cars I’m working on at a time, I never get a complaint. All over the neighborhood, guys are working on their cars. And it’s a terrific neighborhood. So what’s the big deal?”

“Well, look around this neighborhood,” May advised him, taking one hand out from under the dish towel to wave it generally about. “These people are neat, Stan, they’re clean. That’s the way they like it.”

Gazing up and down the street, Stan said, “How do they fix their cars?”

“I think,” May said carefully, “they take them to the garage for the mechanic to fix, when something goes wrong.”

Appalled, Stan said, “They don’t fix their own cars? And they complain about me?”

Don’t Ask (1993) This time a bone is the object. Yes, that’s right, Dortmunder is stealing a bone. Don’t ask.

****What’s the Worst That Could Happen? (1996) Dortmunder tangles with a flamboyant capitalist who might have been modeled on pre-presidential Donald Trump. This joyous book’s victories seem to redeem the manifold losses of the past.

Bad News (2001) Compared to the early years, the tales of Dortmunder’s final decade run smoothly. The crew almost never puts a foot wrong; instead, they are just constantly visited by poor luck. To get the most out of the late Dortmunders, you must have read at least some of the previous adventures. In Bad News the contest between city lawyers in a hick courtroom is the highlight.

The Road to Ruin (2004) I didn’t like The Road to Ruin the first time through because it was so diffuse. But upon rereading, I thought it was great and certainly much more surreal than I understood at first. From our email exchange:

EI: “The crimes are no longer the center of the books: Reporting on life is the center instead. I now adore THE ROAD TO RUIN, which features a kind of daemonic journalism which is perhaps unprecedented. I mean, what are those scenes?!? Chester driving the drunk salesman around? The Harvards vs. the labor schmos? Who else but you would dare to be so underdone in acaper novel?”

DW: “Lemme think about this.” [Later] “I like what you are saying…In all the arts, first you try to please the audience and eventually who you’re trying to please is yourself.”

Thieves’ Dozen (2004) Sentence for sentence, the funniest book of crime stories I know. (Yes, there are eleven of them.) “Too Many Crooks” is the standout.

Watch Your Back! (2005) Dortmunder meets a Tony Soprano-like character and Murch gets to steal a semi on the fly. The first sentence is the great first sentence of the Dortmunder canon:

When John Dortmunder, a free man, not even on parole, walked into the O.J. Bar & Grill on Amsterdam Avenue that Friday night in July, just before ten o’clock, the regulars were discussing the afterlife.

One minor character is a modern musician:

Ralph Medrick listened to “The Star-Spangled Banner” as he’d recorded it during last winter’s Super Bowl—MCXIV?—sung by a nervous girl pop singer with excessive tremolo, an unsteady grasp of key, and not much upper register; cool. His fingers moved on the control panel, adjusting the gains, and the middle range faded, taking with it much of the ambient crowd noise, leaving mainly the aggressive brass sounds, both high and low, like sturdy lines of cathedral columns, with that frightened little voice vaguely wandering among them, a little trapped bird. Nice.

Stop; set coordinates; save; set aside; move on to the Beatles’ “Hey Jude.” Strip away high and low, leaving a broody midrange with tatters of a barely recognizable voice and an obsessive baritone rhythm section pulsing forward like a predator fish, eyes flicking left and right, tail flashing behind.

Reset “Jude”; sync with “Banner”; play both. “Jude” had to be speeded up just a bit to blend with the “Banner” tempo, which served to lift the notes of “Jude” so that they became dissonant with any melodic line played anywhere in the history of the world. The two treated themes weaved discordantly through each other. Now the ruined cathedral columns were underwater, the forlorn “Banner” singer clearly the dinner the predator “Jude” was looking for.

The novelette “Walking Around Money” is included in the Evan Hunter/Ed McBain anthology Transgressions (2005). From DW’s email: “WALKING AROUND MONEY is an oddity, isn’t it? The whole book was Evan’s idea, and he was just determined to make it happen. Twenty thousand word novelettes from 10 writers. We all knew, if he didn’t sell the book, there was nowhere else on earth to sell a twenty thousand word story, but we all went ahead and wrote them anyway; Evan could do that to you. When he first asked me to contribute, I said, ‘Westlake or Stark,’ and he said, ‘Dortmunder,’ so there we are. I’d had the real/fake money idea for 30 years without being able to figure out how to do it. Oh, a novelette.”

When Hunter died I sent Don a condolence. He wrote back: “Evan began as a serious novelist, but that world had ended. He wrote several first-rate novels, completely forgotten. It griped him sometimes, but he was mostly sunny, and if the world wanted him to be Ed McBain, fine. I liked and admired him a lot.”

****What’s So Funny? (2007) The lead, an attorney/heir/modern NYC woman, is subtle and pitch-perfect. It’s hard to believe a 73-year old writer had his finger on the pulse so accurately.

I got to peek inside Westlake’s head a little bit for this one. While he was working on it, he told me that Stan Murch was proud to bring a caper to the table for once: there was a huge dome of gold by the expressway that he thought the gang should steal. Don didn’t know how he was going to work it yet…

But when What’s So Funny? was published, Stan and the dome were there, but not as the main caper, just as a humorous sidebar. I emailed him:

EI: “I have just finished your latest Dortmunder, and thought it was really wonderful. The burglary of the chess set was priceless. Now, I hope they go get that gold dome in the next volume! I think the crew is averaging about 10 G’s per man for a two-month caper these days, huh? Perhaps the moral of the Dortmunder books has turned out to be: Crime pays a moderate wage.”

DW: “I think the purpose of the golden dome was to show the difference between what they do do and total absurdity.”

So there you go. Westlake started to write the golden dome caper, realized that it couldn’t work and still be believable, but kept it in since Stan’s character had said it already.

****Get Real (2009) For his posthumously-published valediction, the great plotter and scenario-imaginer takes down reality TV in meaty chunks. Note how nothing goes according to schedule, like how a big love interest is introduced and…doesn’t go anywhere! Except offscreen with another extra. Genius.

Am I too fanciful or is Babe, the executive producer, somehow Westlake’s own grim reaper, circling like a vulture before ringing down the curtain? Read carefully. At the least, it is rather chilling and moving how Babe sits in the corner, a “stiff” actor, while Dortmunder, Kelp, Tiny, and the kid are asked to reminisce “about the hits of yesteryear.” It’s the last book but the normally unsentimental author gets it in:

The group cut up old jackpots, the bank in the trailer, the emerald they had to keep going back and getting again and again, the ruby that was too famous to hock so they had to put it back where they got it, the cache of cash in the reservoir. The time just seemed to go by.

—

The 5 Tucker Coe novels featuring retired policeman Mitch Tobin

Kinds of Love, Kinds of Death (1966)

Murder Among Children (1967)

Wax Apple (1970)

A Jade in Aries (1970)

Don’t Lie to Me (1972)

and the 4 Sam Holt novels featuring ex-TV Star/amateur detective Sam Holt

One of Us is Wrong (1986)

I Know a Trick Worth Two of That (1986)

What I Tell You Three Times is False (1987)

The Fourth Dimension is Death (1989)

are the only conventional private eye murder mysteries in the Westlake canon. It’s not surprising they’re published under pen names; as the essay “The Hard-Boiled Dicks” makes clear, Westlake was suspicious of the form.

While the Coes and Holts are perhaps really only for Westlake completists, they will still make good reading for anyone who likes to try to “beat the detective” and solve the murder mystery before the hero does. The always-honest Westlake leaves the clues in plain sight; rather to my surprise, without trying, I solved a few of them myself.

The Tobin series offer a basic story arc. At the beginning of the first novel, the lead is emotionally distanced from the world (Tobin is even building a wall in his backyard, not the most subtle of metaphors), but at the close of the series, our hero rejoins his family and society as a whole. There’s a fair amount of amateur psychology throughout the five books, including this self-aware phone call from A Jade In Aries, which doesn’t require a medical degree to unpack:

Marty came on the line after a minute, and I said, “Hello. How are you doing?”

“Don!” he said. “Good to hear from you.”

I said, “This is Mitch. Mitch Tobin.”

“For God’s sake,” he said. “Hiya, Mitch. You sound just like Don Stark. You don’t know him, do you?”

“No, I don’t.”

The Sam Holt tales are comparatively lightweight and feature an ex-TV star, famous for playing “Packard,” a Jim Rockford/James Garner figure. What I Tell You Three Times is False is especially fun, with a cast of fellow actors known for portraying Miss Marple, Sherlock Homes, and Charlie Chan. It’s too bad that Westlake didn’t include more humor in the Holt series, for they just weren’t that serious to begin with, and the final result is a bit stagnant.

—

The two works of nonfiction are more essential for serious Westlakians.

Under an English Heaven (1972) is a huge book that purports to be “a true recital of the events leading up to and down from the British invasion of Anguilla on March 19th, 1969, in which nobody was killed but many people were embarrassed.” The dedication reads: “To anybody anywhere who has ever believed anything that any Government ever said about anything.” Westlake works hard at keeping the comedy coming in what is surely the most well-researched non-fiction history ever done by a crime novelist. Of course, his novels benefitted from his love of research, too, but it’s interesting to look at his style from the wrong end of the telescope. The Paul Bacon cover is fabulous. Used copies can be found online for $30 or new in any Anguilla drug store for $12. Several of the island’s tourist websites proudly reprint the first three pages.

The Getaway Car: A Donald Westlake Nonfiction Miscellany (2014), edited by Levi Stahl, collects terrific fragments from a previously unpublished autobiography and the best of Westlake’s many other non-fiction pieces. In the first edition of this overview, I cited three essays in particular, and I’m pleased to report that they all ended up in The Getaway Car.

During the years that I knew him, Don was mostly kind and generous in his comments about other writers. He wrote introductions to books by Charles Willeford, Fredric Brown, Jack Ritchie, Ross Thomas, James Thurber; in person Westlake spoke admiringly of Peter Straub, Steven King, and Thomas Perry, and said that his oldest friend Lawrence Block was great in every era, including in the current Keller series. Looking though the canon you also can also find praise of George V. Higgins, Elmore Leonard and Len Deighton on occasions when he had no reason to go out of his way to mention them. Westlake also reviewed a lot of non-crime books.

(I did praise James Ellroy once and Don made a face: he didn’t like Ellroy’s sensationalist braggadocio.)

Anyway, all this is to say that the scathing “Don’t Call Us, We’ll Call You” from Xero (1963, collected in The Best of Xero and The Getaway Car) is a real shocker. Lawrence Block mentioned it at the Westlake memorial, saying that the science fiction community — notably Frederik Pohl — had never forgiven him for this early assault on “why science fiction is so lousy.” In addition to Pohl, Westlake takes down Bradbury, Matheson, A.C. Clarke, John Campbell, and many names I don’t recognize, including editor Cele Goldsmith: “A third grade teacher and I think she wonders what in the world she’s doing over at Amazing. (Know I do.)”

“The Hard-Boiled Dicks” from The Armchair Detective (Winter 1984, collected in The Getaway Car) This detailed history of the gumshoe is some of the best crime novel criticism I’ve seen. Westlake argues that genre fiction begins with an iconic image, transforms into ritual, and ends up as pastiche, even concluding with an indictment against writing private eye novels today (although he didn’t always follow that advice himself). Some of the writers discussed are obvious (John Carroll Daly, Hammett, Chandler, Spillane, and Ross MacDonald) and some are not (Lester Dent, Forrest Rosaire,and Shell Scott). Westlake praises Hammett, barbs lightly at Chandler, really goes after Ross MacDonald, and compares first paragraphs of Daly, Hammett, and Spillane in an eye-opening way.

“Peter Rabe” from Murder Off the Rack: Critical Studies of Ten Paperback Masters (1989, collected in The Getaway Car) Westake always avowed his indebtedness to Rabe, whom he cited with Hammett as one of his biggest influences. Rabe’s name would be much less familiar to readers today if Westlake hadn’t been so vocal in his acclaim. This important essay looks at all the major Rabe books in chronological order. Westlake doesn’t like all the novels equally, and in interview shortly before he died, Rabe said he appreciated Westlake’s honesty.

—

Other bits from our correspondence:

DW: “Originally I was supposed to be in DC for Laura Bush’s National Book Festival, a thing we did the first time she ran it, the weekend before 9/11, the only time we’ve ever been in the White House. But I just couldn’t do it, and begged off. I’m not going to go public and rant and rave about that bunch, but I can’t be complicit.”

When I asked what dietary restrictions he and Abby had when coming for dinner, he responded, “None. If it moves slowly enough, we’ll eat anything.”

When I sent him a long quote from John D. MacDonald’s Soft Touch (the bit about money when they open the suitcase), he responded, “John D. was a born writer, which is the same I guess as a born poet. He would drop into these riffs every once in a while, and they were wonderful. I remember one where a guy on death row suddenly starts feeling what he calls nostalgia for all the things that won’t be; the wife, the kids, the experiences. ‘I won’t be coming down the track of time to you.’ None of those riffs are necessary, but life wouldn’t be the same without them.”

After he sent me a copy of Charles Willeford’s own typed manuscript of the unpublished Grimhaven, I sent him a thank you note and called it “exceptional.” He wrote back, “It is not just an exception in his oeuvre, but in the world. Those who will be knocked out by it should see it.”

—

Don, thanks for a memorable chapter in my life! I’ll never forget meeting and getting to know a literary hero.

But really, thanks for all the goddamn great books. In way, I can’t even be that sad you have passed on: you did here exactly what you were supposed to do.

Donald E. Westlake, 1933 – 2008.

—

Bonus track 1:

The Armchair Dectective Book of Lists includes a selection of favorite mysteries that reveal quite a bit about Westlake’s tastes and influences.

The Hoke Moseley series by Charles Willeford These surreal police procedurals were relatively recent when Westlake made this list. He had blurbed,“Hoke Moseley is a magnificently battered hero. Willeford brings him to us lean and hard and brand-new.” Undoubtedly Westlake also appreciated Willeford’s strong declarative sentences.

The Red Right Hand by Joel Townsley Rogers is sort of as if H. P. Lovecraft wrote an Ellery Queen mystery. Westlake told Ed Gorman in an interview, “I believe Joel Townsley Rogers’ The Red Right Hand should be reissued every 5 years forever.”

Kill The Boss Goodbye by Peter Rabe See the discussion of the Rabe essay above.

The Coffin Ed/Digger Jones series by Chester Himes The two cops don’t really ever win big and are constantly derailed by minor but surprising events, just like classic Westlake characters.

The Maltese Falcon by Dashiell Hammett From my fanboy chair, I’m a little surprised Westlake plumped for this one. It’s one of the greatest, of course, but many serious Hammett readers think The Glass Key is even greater. On the other hand, the exotic treasure theme of Falcon was borrowed by Westlake on more than one occasion.

Westlake wrote about The Thin Man and The Dain Curse extensively in the essay “The Hard-Boiled Dicks.” He also solved what he considered the “problem” of Red Harvest in a movie treatment that was never produced.

The “problem” is simply that the first murder mystery concludes about a third into the book. (The bank teller killed the publisher out of mistaken jealousy.) It’s hard to comprehend why and how the Op stays in the action, playing both sides against the middle, after that first proper wedge of plot is given away. Of course he has the elder Willson “sewed up,” but, still, why is the Op so committed? And why do all the criminals grant him access into their dealings? While the Op was looking for the murderer of young Willson, it all made a bit more sense.

I don’t have this “problem” with Red Harvest, I think it is a masterpiece. But Don was a stickler for believability and this really bothered him when writing the script. In the screenplay there’s more about the Op and his almost love interest Dinah Brand that “solved” the motivation for the Op. From my comfy fanboy chair, I’m surprised that Westlake was comfortable rewriting Hammett to such an extent.

Westlake also tried to write a screenplay for The Dain Curse. There’s too many characters for a movie script, so the first thing he did while rereading the book was note which minor players to leave out. He could only cut one, and in the last pages that person was revealed as the murderer, so he gave up the project.

Interface by Joe Gores In “The Hard-Boiled Dicks,” Westlake calls this book a good modern interpretation of the private-eye tradition. Gores was also a close friend: both Plunder Squad and Drowned Hopes share chapters with Gores characters.

The Eighth Circle by Stanley Ellin The murder plot is almost incidental in this superb and realistic portrait of the 1950’s-era gumshoe. It’s easily Ellin’s best longer work, who is more famous for his short stories.

Sleep and his Brother by Peter Dickinson Atmosphere takes precedence over plot in Dickinson’s fascinatingly erudite English crime novels. Sleep stars Jimmy Pibble, the London policeman with remarkable intuition.

A Coffin for Dimitrios and The Light of Day by Eric Ambler Dimitrios is grim, Day is comic, and there is not an extra word or unflawed character between them. The Light of Day is a clear influence on some of Westlake’s comic capers.

—

Bonus track 2, from April 2013:

When Levi Stahl was assembling The Getaway Car I helped him look though Donald E. Westlake’s attic.

I felt a chill when I discovered the shelf of homemade research books.

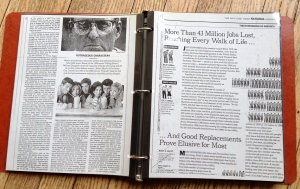

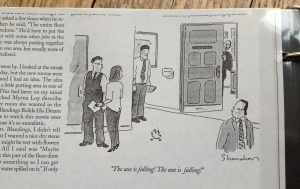

Among other tools,here was Westlake’s own large compilation of relevant New Yorker cartoons and NY Times articles for The Ax.

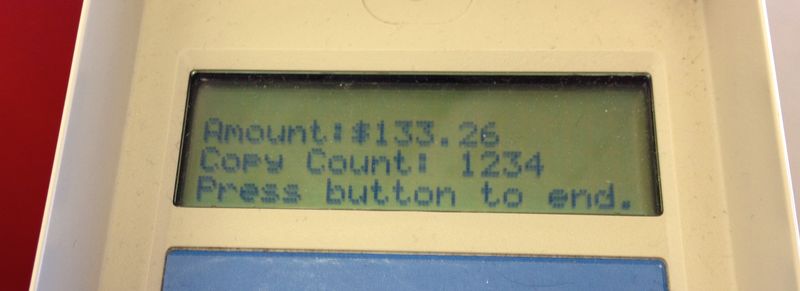

There was a spooky visitation while spending over an hour running photocopies for Levi at Staples. Sarah and I kept wondering when I’d run out of paper. The machine finally did… right after completing the first full copy of the autobiography, and with the copy count right at 1234.

Also in the attic were reams of correspondence with carbons of his typewritten responses. Long after the advent of word processing, Westlake still wrote his books on his beloved Smith-Coronas. From the last decade, I was amused by plantive letters from young publishing underlings requesting Word docs or PDFs. Westlake curtly refused, of course. They would get only big boxes of neat Courier typescript from Donald E. Westlake.

In several interviews, Westlake said he didn’t outline, but I did find a few page-long notes on plot. Indeed, there was one reference page that had the whole outline of the last two Parkers, Ask the Parrot and Dirty Money. (Talk about fanboy gold…)

Much more frequent than outlines were single-spaced, unparagraphed, sloppy first drafts of chapters running all over both sides of a page. My guess is that when inspiration struck, he just turned up the gas and didn’t stop for anything. Then the second draft was a fair copy with very few mistakes and even fewer edits.

I opened up the box of Dirty Money to look at the famous last line that I cite above.

Westlake was a worker. He’d write anything he thought was interesting or had a chance to survive. Levi and I didn’t find any other novels, but we did find about two file drawers of finished, never-produced film and television scripts. This isn’t exactly a surprise, but according to the contracts, it is indeed true that submitting unused ideas for a James Bond film pays ten times the advance for a completed novel.

My heart was warmed looking at the “contract” for the essay on Peter Rabe for Murder Off the Rack. No advance, and future royalties split between all ten of the anthology’s contributors. It’s safe to say that Westlake never made a dime from it. He wrote the essay because he thought it was important to do, and he was right.

—

Very special thanks to Abby Westlake.