[Update: Two weeks later: The sudden death of Geri Allen is a profound shock.]

Geri Allen is 60 today. Happy Birthday Geri!

Allen has had a long career of triumphs and remains one of the key musicians in jazz, but she may not always get enough credit for the degree of influential innovation on display from about 1984 to 1989.

Kenny Kirkland took the virtuosic McCoy Tyner/Herbie Hancock/Chick Corea axis to its logical endpoint. Around the time of Kirkland’s greatest prominence, Geri Allen broke something open by offering a radically different approach, bringing back the surrealism of Thelonious Monk and Eric Dolphy.

Allen’s solution would go on to be vastly influential. There were other avatars from the late 80s and early 90s, perhaps most notably Marcus Roberts and Brad Mehldau. Many of the celebrated younger pianists of the current moment — a recent poll has names like Jason Moran, Vijay Iyer, Craig Taborn, David Virelles, Kris Davis, Matt Mitchell, Aruán Ortiz — don’t play like Kirkland, Roberts, or Mehldau. They play like Allen.

—

Allen hails from Detroit, where the late Marcus Belgrave was a crucial mentor to so many musicians. Belgrave shares a birthday with Allen (he would have been 81 today) and an informal duo from 1993 where he talks a little bit before playing Allen’s “Dolphy’s Dance” is a precious document. (Thanks to Mark Stryker for this paragraph.)

Once her reach began extending past Motor City, word got around fast. In the mid-80s everyone was talking this newcomer with an unprecedented command of the whole history of jazz piano, where a bluesy ethos was naturally married to a profound embrace of the avant-garde.

It was both sides that made her so special. She was so out, and so in. Atonal cascades, African vamps, swing, fusion. Fire in all directions. In the mid-80s, very few could say they could play with anybody, but Allen could cross any bridge.

On Allen’s first album, The Printmakers from 1984, the future was foretold. It sounds like a release made yesterday by a modern poll-winner except richer and more deeply connected to tradition. Bass virtuoso Anthony Cox and honored master Andrew Cyrille complete the ancient-to-the-future trio.

“A Celebration of all Life” = wild vamps.

“Eric” = surreal waltz.

“Running As Fast As You Can… tgth” = unprecedented form, melody and improvisation for just bass and drums before they do it all again with piano.

“M’s Heart” = solo gospel.

“Printmakers” = boogie and swing.

“Andrew” = arco bass and tympani doubling the melody.

“When Kabuya Dances” = joy.

“D and V” = chorale conclusion.

Allen followed up with Homegrown, an impressive solo recital with fractured readings of two Monk pieces. A reasonably inside reading of “‘Round Midnight” goes straight into the righteous chaos of “Blue.” Don Pullen could also marry Monk and Cecil Taylor with an heightened African thread; Stanley Cowell is in there too. But Allen seems to have the most unified and streamlined blend of conventional jazz harmony and pure atonality. The opening “Mamma’s Babies” has it all, a manifesto of African avant-garde blues and riffs.

The next pair of Allen dates have synthesizers, overdubs, vocals, and other borrowings from popular music and fusion anchored by a hometown rhythm section of Jaribu Shahid and Tani Tabbal. Open on All Sides in the Middle is a full band and Twylight is an expanded trio session. Perhaps not every production choice has aged well (it was the 80s, after all) but the compositional integrity is striking. The slinky/fractured horn lines on Open on All Sides are really beautiful. Twylight has a concentrated offering of Allen’s odd meter vamps that feel old and fresh at the same time. Over those vamps Allen plays pretty chords, bluesy melodies, or jagged shapes. Everyone does this today, but at the time it was rousing call to arms.

“Skin” from Twylight

An acoustic version of music from Twylight and The Printmakers on tour in Minneapolis with Anthony Cox and force of nature Pheeroan ak Laff in about 1989 made a powerful impression. At least two compositions for the Bad Plus, “Boo-wah” and “Do Your Sums, Die Like a Dog, Play for Home,” are my attempts to digest and reshape that profound influence. It’s probably just the ravings of a fan boy, but I have often thought if Allen had kept the trio with Cox and ak Laff and developed that language further they would have changed the course of jazz. I’m still waiting to hear a bootleg: Cox told me they played the Village Vanguard and other places.

The best meeting of Allen and ak Laff on record is Oliver Lake’s Gallery, a superb quartet session with Fred Hopkins. (Rasul Siddik joins on one track.) Gramavision dates were unusually well-engineered for the era: Fred Hopkins is always impressive but this LP recorded by Jim Anderson shows him in an especially positive light. Lake’s tunes are wonderfully charismatic and the whole band is clearly having a great time. Allen’s comping is deft and subtle. In a freer context pianists can swamp the harmony with endless sound, but Allen always offers light and shade.

Allen made a special study of Eric Dolphy. Her composition “Dolphy’s Dance” is two glorious choruses of angular rhythm changes.

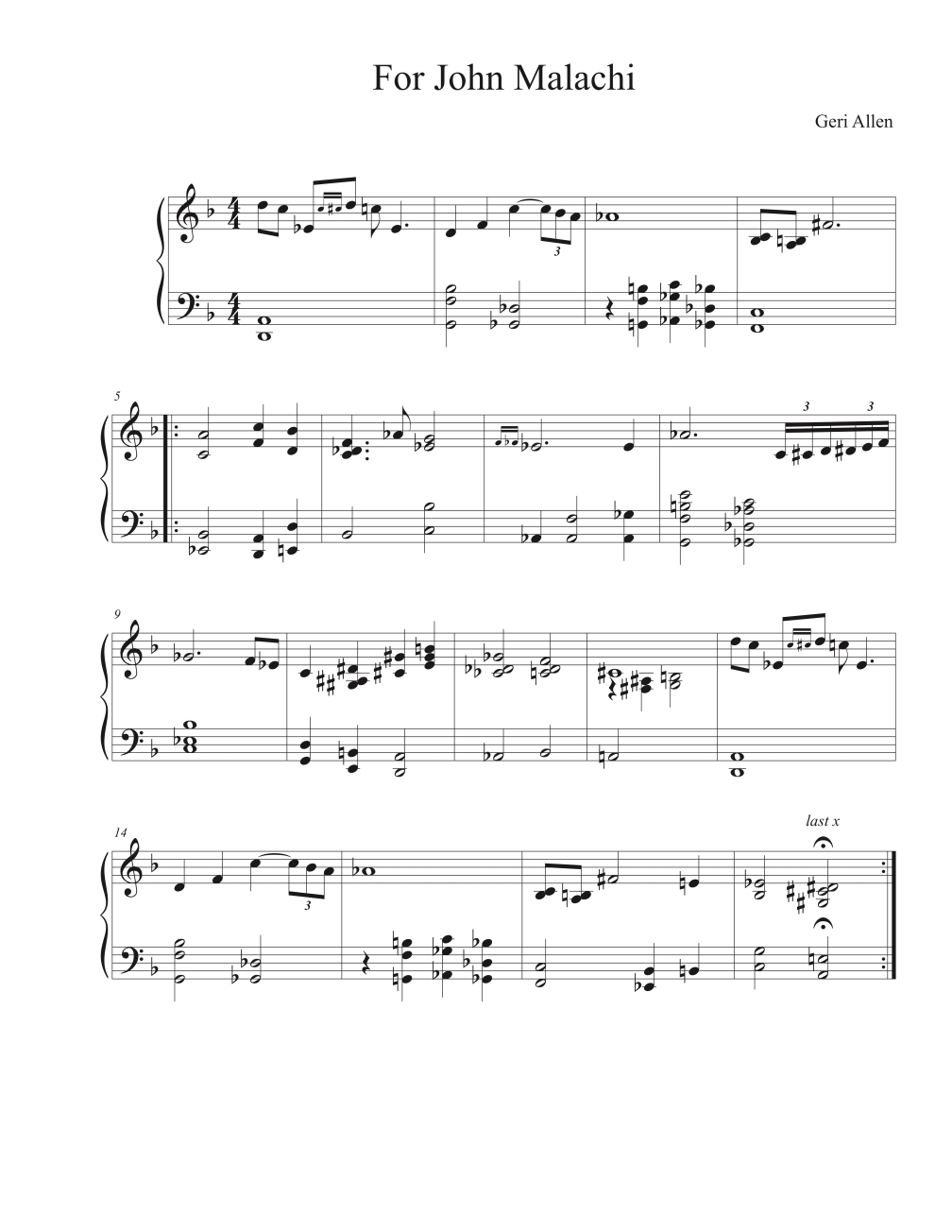

“Dolphy’s Dance” is hard to hear. I consulted a few recordings and this is my best guess…It’s still not accurate though

In the early years, Allen was the “Eric Dolphy of the piano.” Dolphy could play his unexpected lines in any context and as a sideman raised any album into an “event.” Allen had that power as well. On one of Allen’s earliest dates, Frank Lowe’s satisfying Decision in Paradise, she is comfortable next to heroes Don Cherry and Grachan Moncur, impressing with a surreal opening chorus to “You Dig!” that couldn’t be played by anyone else. From the other end of the spectrum, her fierce angularities transform Franco Ambrosetti’s Movies, for example the absurd latin bit on “The Magnificent Seven.”

A terrific place to enjoy Allen as an “X-factor” are three discs of muscular “young lion jazz” under the leadership of Ralph Peterson. The excellent quintet sessions with Terence Blanchard, Steve Wilson, and Phil Bowler, V and Volition, are perhaps a tad unfocused with many long solos over a relentless rhythm section. Triangular with Essiet Okon Essiet (and Bowler one track) has greater claim to truly classic status, in part for the frisky readings of “Just You, Just Me” and Denzil Best’s “Move.”

Even more essential is Etudes with Charlie Haden and Paul Motian. A humble Soul Note date with clear and unfussy engineering by Jon Rosenberg has gone to be an undeniable milestone. “Lonely Woman” was the first truly acceptable version of Ornette Coleman’s most famous ballad with piano in the lead. (In her DTM memorial comment for Charlie Haden, Allen recalls that Ornette walked in the studio while they were tracking that very piece.)

In its way, Etudes is an album of tributes: while Ornette, Dolphy, and Herbie Nichols are cited directly, the gods of Monk, Paul Bley, and Andrew Hill are also obviously present. (Part of what makes the disc fresh is how little reference to there is to the Motian/Haden piano lineage of Bill Evans or Keith Jarrett — indeed, there is more Jarrett on Allen’s own albums with gospel-related vamps.)

Paying this much overt attention to history is in stark contrast to Allen’s own 80s albums or Lake’s Gallery, all of which are more concerned with “present day.” This temporal flexibility is traditionally a hallmark of a jazz master, but as the history has kept accruing, it has gotten harder to command the whole territory. Mary Lou Williams was also interested in viewing it all from one vantage point; drawing a line from Mary Lou to Geri is as easy as going from A to B.

While the Allen/Haden/Motian trio would make several more records and tour big festivals, nothing would top Etudes in terms of freshness and easy blend between the three idiosyncratic greats. However, the follow-up The Year of the Dragon opens with a blazingly fast “Oblivion”and remains one of the best Bud Powell covers ever recorded. The second track is Allen’s extraordinary “For John Malachi”

This quick survey of Allen’s early years hardly covers everything. There was an important association with Steve Coleman and record dates with Dewey Redman and Wayne Shorter — not to mention all the great music Geri Allen has played since 1989.

But for now, on the occasion of her 60th, I just wanted to make sure that the official record was correct. In this music, there was before Geri Allen and after Geri Allen. She’s that important.

“Free the Fire” was first heard trio with Ron Carter and Tony Williams; there’s also a great version with Betty Carter.